“The breath of the tens of thousands of people jammed against one another rose up in a white cloud so thick that it could be seen the swaying shadows of the bare March trees. It was a terrible and a fantastic sight” Yevgeny Yevtushenko wrote, describing the crowds that had gathered on the streets of Moscow in the wake of Stalin’s funeral in mid-March, 1953. The city streets were full of people trying to see Stalin’s body, displayed at the Hall of Columns. In his description of the scene, he went on to describe death and injury, declaring that “[Stalin] could not be innocent of the disaster,” even though he was dead. The implication was clear—although Stalin had died, his influence would be keenly felt in the Soviet Union. Joshua Rubenstein’s The Last Days of Stalin explores that influence not only in the Soviet Union but abroad as well.

Stalin’s demise likely started with a stroke at his home on the outskirts of Moscow. Rubenstein starts with the end of Stalin’s rule, the last days of his iron grip on the Soviet Union as his successors had already begun to dismantle some of his more egregious policies. The domestic political situation in the Soviet Union at the time of Stalin’s death was dominated by what was known as “The Doctor’s Plot,” a thinly veiled anti-Semitic campaign against Jewish doctors who were charged with attempting to assassinate high-ranking Soviet officials, and a power struggle among members of Stalin’s inner-circle.

Before Stalin’s death, a number of Jewish doctors had been arrested as a part of the plot and were arrested and interrogated, resulting in two of the accused doctor’s deaths. Rubenstein suggests that “The Doctor’s Plot” could have been an early stage of a renewed series of purges, harkening back to the Terror in the late 1930s. If this was Stalin’s intention, and there isn’t clear evidence to support this, it was never realized.

After his death many of the accused were pardoned and released—but this wasn’t where reforms stopped. A number of the forced labor camps were partially dismantled as Stalin’s successors put a halt to what they deemed were unnecessary or wasteful projects and pardoned or remitted the sentences of prisoners whom had committed minor offenses.

As they worked to dismantle Stalin’s policies, plots, and camps there was still one thing that remained to be seen: who would Stalin’s successor be? As Rubenstein tells it, the choice was either Lavrenti Beria or Nikita Khrushchev, both of whom had been in Stalin’s inner circle and had been closely associated with his arranging his care in the wake of his sudden illness. By exploring both of their responses both in the immediate wake of Stalin’s death, and throughout the next few months, Rubenstein carefully traces how Khrushchev triumphed and Beria wound up in jail. Beria’s arrest was justified by the claim that he would have certainly renewed the purges, and might have been even worse than Stalin.

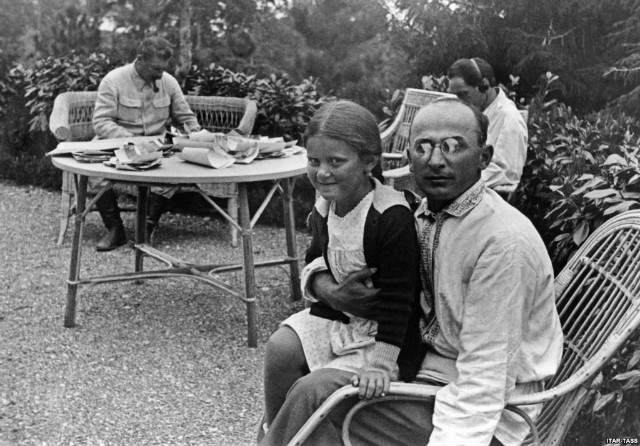

Lavrenti Beria sitting with Stalin’s young daughter, Svetlana, and Stalin (background), and Nestor Lakoba.

Rubenstein also pays attention to the responses of foreign powers, both Western and Eastern bloc, to the end of Stalin’s reign. Rubenstein makes it clear that many countries, but most particularly the United States and its recently inaugurated President Dwight Eisenhower, struggled with the appropriate response to the sudden political upheaval. Though the “window of opportunity was probably narrow” for the United States and the Soviet Union to come out on the other side with a better relationship, Rubenstein argues that the United States was not adequately prepared for the leadership change and the ways in which Stalin’s death had fundamentally altered the internal political situation of the Soviet Union.

Rubenstein’s account of Stalin’s final days of life and influence is engaging and well-written. Throughout the work, Rubenstein carefully contrasts the official narrative of Stalin’s life and death set forth by the Kremlin, with memoirs and other personal accounts, including political actors, Stalin’s daughter, and cultural figures such as Yevtushenko. Rubenstein candidly admits when sources are troublesome – memoirs that may have been colored by the personal motivations of the authors or because they were written sometime after the events that occurred, and could have been influenced by later political events.

|

| Stalin in 1945 at the Berlin Conference. By the time of Stalin’s death, witnesses say that Stalin appeared to have thinner hair, more wrinkles, and difficulty moving. |

However, some aspects of the book may be difficult for those without background knowledge of Stalin’s reign or the international political situation in the early 1950s. Rubenstein does an excellent job of illustrating the fear of Stalin, both at the Party and ground level, but someone looking for an explanation of where that fear originated and why it was so powerful may need to look elsewhere. Rubenstein’s frequent engagement with the United States’ response to the events could have also included some additional background to provide a little more context for the early Cold War hostilities. While The Last Days of Stalin does a terrific job of exploring “The Last Days,” a little more build up to them would have been effective.

The Last Days of Stalin is clear and concise, and successfully integrates a number of different voices and characters into a coherent narrative of a tumultuous time. Rubenstein’s treatment of the topic should prove an interesting and quick read for scholars and students with an interest in Stalin and his immediate legacy, the early days of the Cold War, and a knowledge of the USSR’s domestic and international political situations of the mid-twentieth century.