I was lucky enough to grow up on the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. To the west, steep forested peaks with crystal-clear lakes and streams. To the east, sweeping plains dotted with prairie dog holes and duck marshes. Rocky Mountain National Park was less than two hours away, as was Pawnee National Grassland. I took countless trips to both and many more federal areas like them. And I came to realize then, guided by a father who made a successful and rewarding career with the United States Forest Service, that my many happy memories of camping, fishing, and hunting trips in a variety of federally-protected areas would not have been possible without the conservation movement, and suffice it to say, several environmentally-conscious presidents, too.

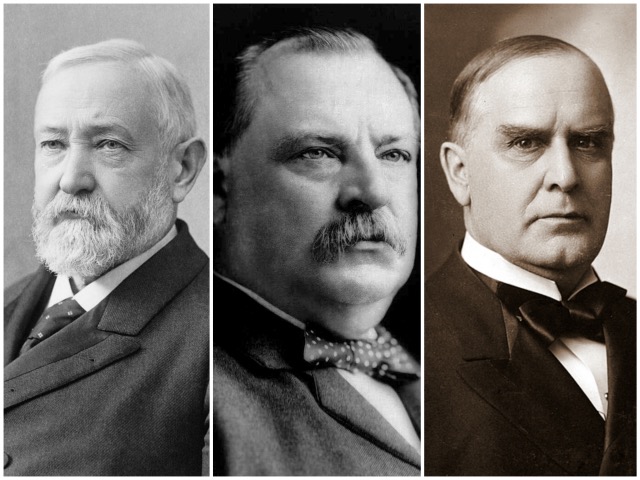

And that impulse—conserving public lands across the nation in the service of the national public good—is the focus of Otis L. Graham, Jr.’s Presidents and the American Environment. The book focuses primarily on conservation efforts and not so much “the environment” writ-large. After an introductory chapter covering a “first century without a national vision,” Graham covers the presidents in chronological order beginning with the unimpressive trio of Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland, and William McKinley.

|

| Presidents Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland, and William McKinley. The major similarity? Their general indifferene toward conservation. Their major difference? A gradual reduction in facial hair. |

Venturing forth, the reader finds a series of chapters organized around either a single president or several. Less a narrative, the book presents what might be more accurately labeled vignettes of each president, along with the major environmental issues he faced and the key players who surrounded him. The two Roosevelts—Teddy and Franklin—are the only presidents to merit a chapter of his own.

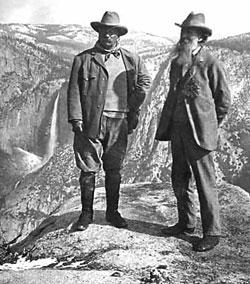

|

| President Theodore Roosevelt helped solidify conservation as a national agenda item along with preservationist John Muir. |

At times, the groupings make perfect sense: William Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover are all lumped together for their fuzzy pro-market approaches to conservation—a departure from the vigorous conservation agenda of Theodore Roosevelt.

But it appears that social movements—and not presidents—just as often drive Graham’s narrative. In another chapter subtitled “Environmentalism Arrives,” Presidents Lyndon Baines Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter mix it up. In yet another case, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton are thrown together in a somewhat bewilderingly-themed chapter subtitled “Presidents Brown and Green.”

Organizational issues aside, the writing can really shine through, often making this reader chuckle. After noting that TR essentially preserved one out of ten acres of U.S. land (including Alaska!), Graham lays bare what was has been at stake had the more assertive conservation presidents like the two Roosevelts failed to act. If not preservation, Graham writes,

Imagine Donald Trump buying Yosemite as home for several lit-up resort hotels and casinos with their sprawling parking lots . . . the Mormon Church buying and closing Bryce Canyon to all but its members, and my family but not yours (because my great-grandfather, not yours, obtained it by fraud during the great land giveaway of the nineteenth century) enjoying a splendid, gated summer camp in one of the remaining groves of sequoias not felled to provide building material for expanding US cities and suburbs.

In another instance, the author presents a humorous “imagined conversation” between Presidents Teddy Roosevelt and Benjamin Harrison “here in the Afterlife!”

Presidents and the American Environment arrives at a perfect moment, one when conservatives have launched a state-by-state effort to decentralize control of well-regulated and managed federal lands down to the state level. Invoking the spirit of Warren Harding or Calvin Coolidge (though they may not realize it), they have also aligned themselves in the short term with the lawless Clive Bundy—neither realizes that there is a great public value inherent in places like Roosevelt National Forest, Yosemite, Yellowstone, or Death Valley.

In this context, Graham’s work reminds us of the personalities it took to preserve these areas and why land was worth preserving in the first place at the national level. But readers looking for overarching themes or lessons from presidential history might be disappointed, or at the least, find them hard to spot. Most readers, nonetheless, like this one, will enjoy the countless interesting anecdotes, refreshing and at times quirky prose, and the breadth of material covered—great fodder for both relaxed reading and dinner-party conversation.

To the dedicated, interested reader—Graham offers a treasure trove of facts and telling anecdotes, from Hoover declaring, in the wake of TR’s monumental presidency, “Conservation is the settled policy of the government,” to the fact that John Kennedy “preferred to spend time with the ‘girls and mattresses’ that came on the backup plane” to spending any time in the actual wilderness during his Western excursions.

Yet the lack of a strong argument is all the more disappointing given that the pendulum has swung so heavily toward anti-conservation interests. Several presidents, like Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Hoover, Harry Truman, and Dwight Eisenhower tended to encourage extractive industries to operate on federally-owned land and to push the construction of ever-larger dams. Today, Senator John McCain, along with several other conservative politicians, is pushing a similar agenda of private and corporate profit over preserving the public’s environmental inheritance. One of these agenda items is a bill to allow highly destructive copper mining on a swath of land in Arizona which the Apache consider sacred.

Graham’s hesitancy to present a full-blown, overarching point not only tends to leave each chapter feeling a bit directionless, but it makes this reader wonder, how important have presidents—as a whole—really been to conservation? Graham offers in the introduction that they, generally, “have mattered, a little or a lot.” And he illustrates that Teddy and FDR at least pulled more than their weight, with TR forcing conservation onto both parties’ national agendas for decades to come and FDR splicing “conservation into the Democratic Party’s DNA.” But for so many of the others, it remains unclear what made each president do what they did, or didn’t do, in the larger environment of American history.