In January 2018, President Donald Trump made a set of disparaging comments about Puerto Rico. They underscored just how little many Americans understand about the value and complexity of the relationship between the 50 states and this island territory. In fact, Puerto Ricans are Americans—making our relations not foreign, but familiar or even familial.

There are 3.4 million inhabitants of the island of Puerto Rico, and another 4.9 million Puerto Ricans residing in other parts of the United States, yet many Americans living in the “Fifty Nifty” are unaware of the shared history. The confusion begins with Puerto Rico’s political status as a commonwealth, with questions about sovereignty, and with a culture that is both different and deeply American. So here are ten moment to help better understand Puerto Rico.

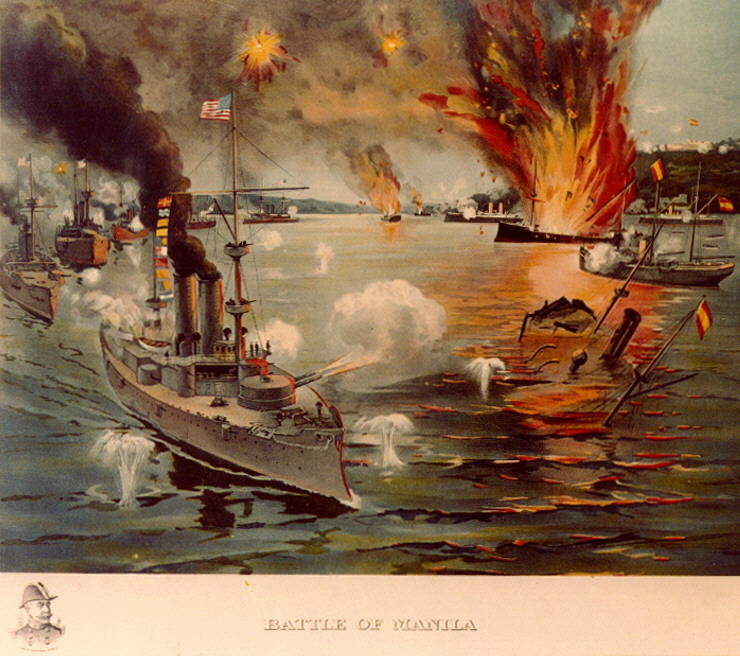

1. Welcome to America: The Spanish-American War and Post-War Legislation, 1898-1917

When the dust kicked up by Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders settled and the USS Maine had been properly avenged, the Treaty of Paris—signed December 10, 1898—officially rid the Western Hemisphere of European powers and firmly established the United States as the dominant force in the region. The treaty gave control of Puerto Rico (along with Cuba, Guam, and the Philippines) to the United States, and made Uncle Sam the unquestioned authority in the Caribbean, with tight control over Puerto Rico’s trade and other affairs. That control did not really loosen, even after the Foraker Act in 1900 (that allowed Puerto Rico limited local government) or the 1917 Jones Act (that granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans).

2. A Party of Their Own: Partido Popular Democrático, 1938

Logo of the Partido Popular Democrático (Popular Democratic Party).

The Partido Popular Democrático (PPD, Popular Democratic Party) was founded in 1938. Though it grew out of earlier movements either for statehood or for independence, it was largely concerned with making life better for Puerto Ricans. The PPD sought land and labor reform, appealing to the middle and rural working classes and saw gradual autonomy as its goal. Luis Muñoz Marín was the leader of the party. In a significant act of being a good neighbor, President Harry S. Truman called upon PPD member Jesus T. Pinero to be the first native-born governor of Puerto Rico in 1946. One year later, Puerto Rico gained limited self-government and in 1948 elected Marín to be governor. He served four terms.

3. Ties that Bind: Establishment of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, 1952

The coat of arms of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

On July 3, 1950, President Truman signed a bill to make Puerto Rico a commonwealth. This meant that it would have autonomy in internal affairs while still adhering to U.S. laws. The U.S. maintained control of international affairs including trade, defense, immigration, and diplomacy. Eleven months later, Puerto Ricans voted overwhelmingly in favor of the Commonwealth Bill and delegates began drafting a Constitution. The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico was adopted in San Juan on March 3, 1952 and in Washington, D.C. on April 22, 1952.

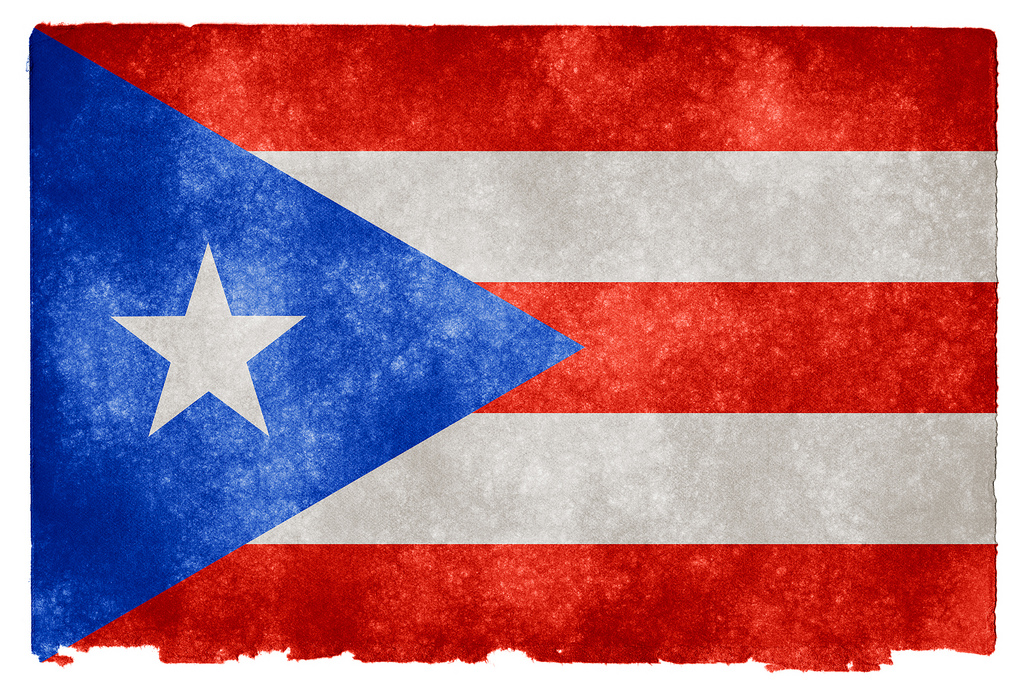

4. Puerto Rican First: Nationalism and Nationalist Opposition

The flag of Puerto Rico, adopted in 1952.

At the time of the Commonwealth Bill, a referendum in Puerto Rico revealed 81% of the Puerto Rican public were in favor of it. But anti-United States sentiment and nationalist groups in Puerto Rico grew in other circles. Puerto Rican nationalists saw the Commonwealth Bill as an extension of what they claimed was modern American imperialism.

In response to President Truman’s support of the bill, two Puerto Rican nationalists living in New York attempted to assassinate the president on November 1, 1950. They hoped the plot would further the case for independence and promote continued protest. Four years later, on March 1, 1954, four Puerto Rican nationalists stormed the U.S. House of Representatives with hand guns, shouting independence slogans and firing over 30 shots. They injured five congressmen. All of them survived and the four shooters were arrested within the day.

A repeat plebiscite in 2012 revealed 54% of Puerto Ricans were no longer in favor of the commonwealth status.

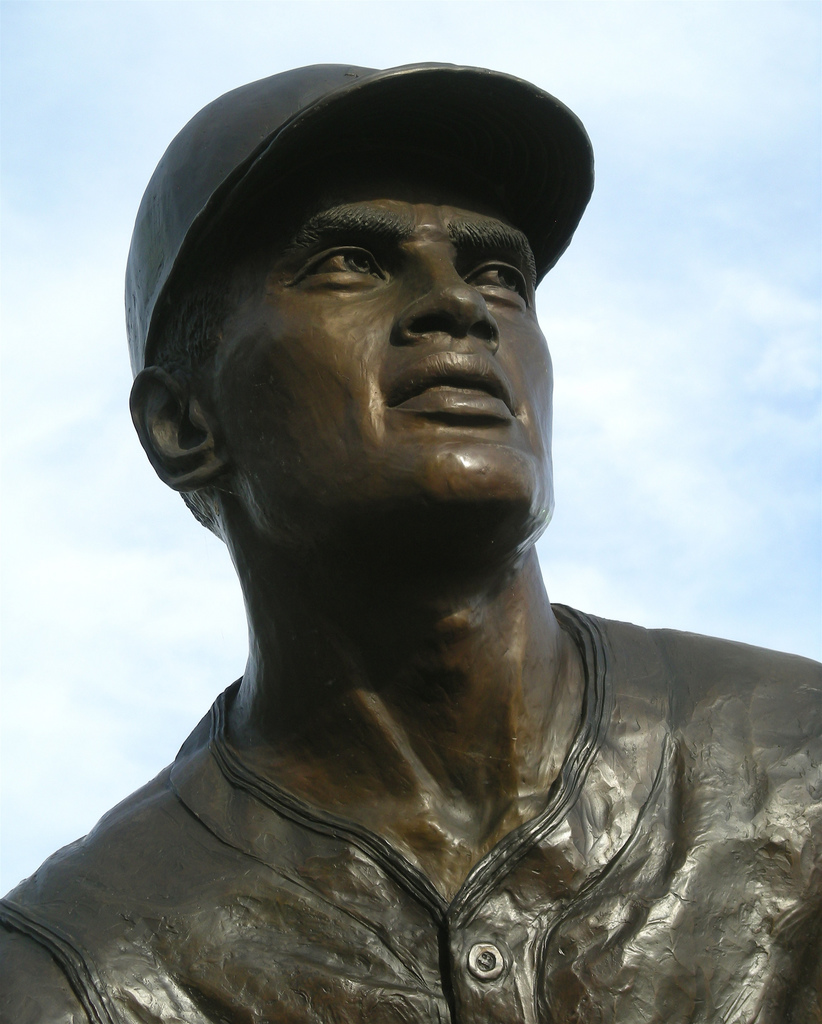

5. Roberto Clemente: Puerto Ricans and the National Pastime

A statue of Roberto Clemente, located at the Pittsburgh Pirates' PNC Park.

Puerto Ricans love baseball and no Puerto Rican played it better than Roberto Clemente. He began playing in the big leagues in the 1950s. In addition to leading the Pittsburgh Pirates to two World Series victories, Clemente earned multiple batting titles, Gold Glove Awards, and became the 11th player in history to record 3,000 career hits. His athletic career not only solidified his status as a stellar baseball player, but brought Puerto Rico into better focus in the minds of mainland Americans. His tragic death in a plane crash en route to aid Nicaraguan earthquake victims in 1972 burnished his golden image, memorialized with his posthumous induction into the Hall of Fame one year later.

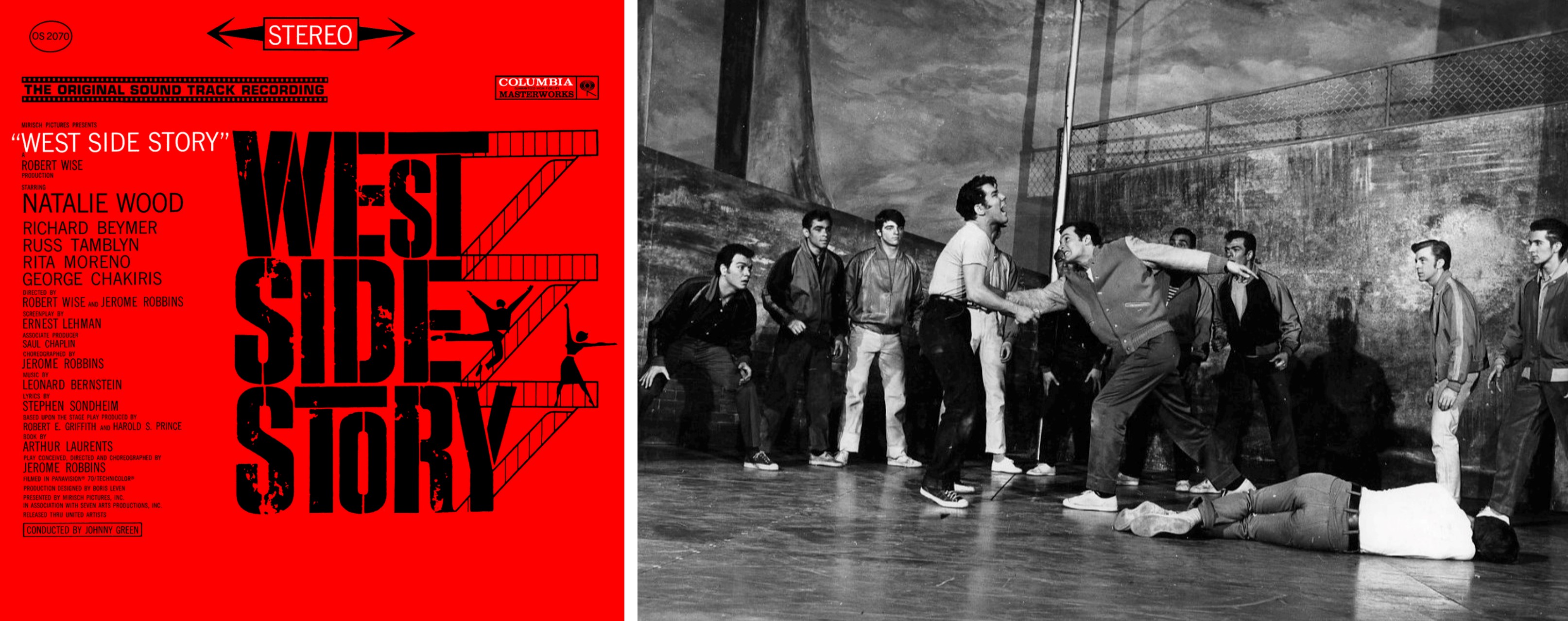

6. West Side Story: a Broadway Fiction of an Unfortunate Reality

Cover of the soundtrack album from West Side Story (left), and a scene from "the rumble" segment of the Broadway play (right).

Tension between white New Yorkers and the Puerto Rican community in that city was immortalized in 1957 when Leonard Bernstein composed the Broadway musical West Side Story. The show was a major success and in 1961, Robert Wise joined the musical’s director, Jerome Robbins, in committing it to film.

Telling the tragic story of a gang rivalry between the Jets (white New Yorkers) and the Sharks (Puerto Rican New Yorkers), Robbins and Wise intended to highlight the treatment of the Latino community in Manhattan in the 1950s. The musical film earned ten Academy Awards, including Best Supporting Actress for Puerto Rican Rita Moreno. She played Maria, the baby sister of the Sharks’ leader who falls in love with Tony, the co-founder of the Jets. West Side Story follows the forbidden love between Maria and Tony, ending tragically with Maria blaming the multiple deaths throughout on pointless gang violence.

7. Taking It to the Streets, and the Hill: Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN)

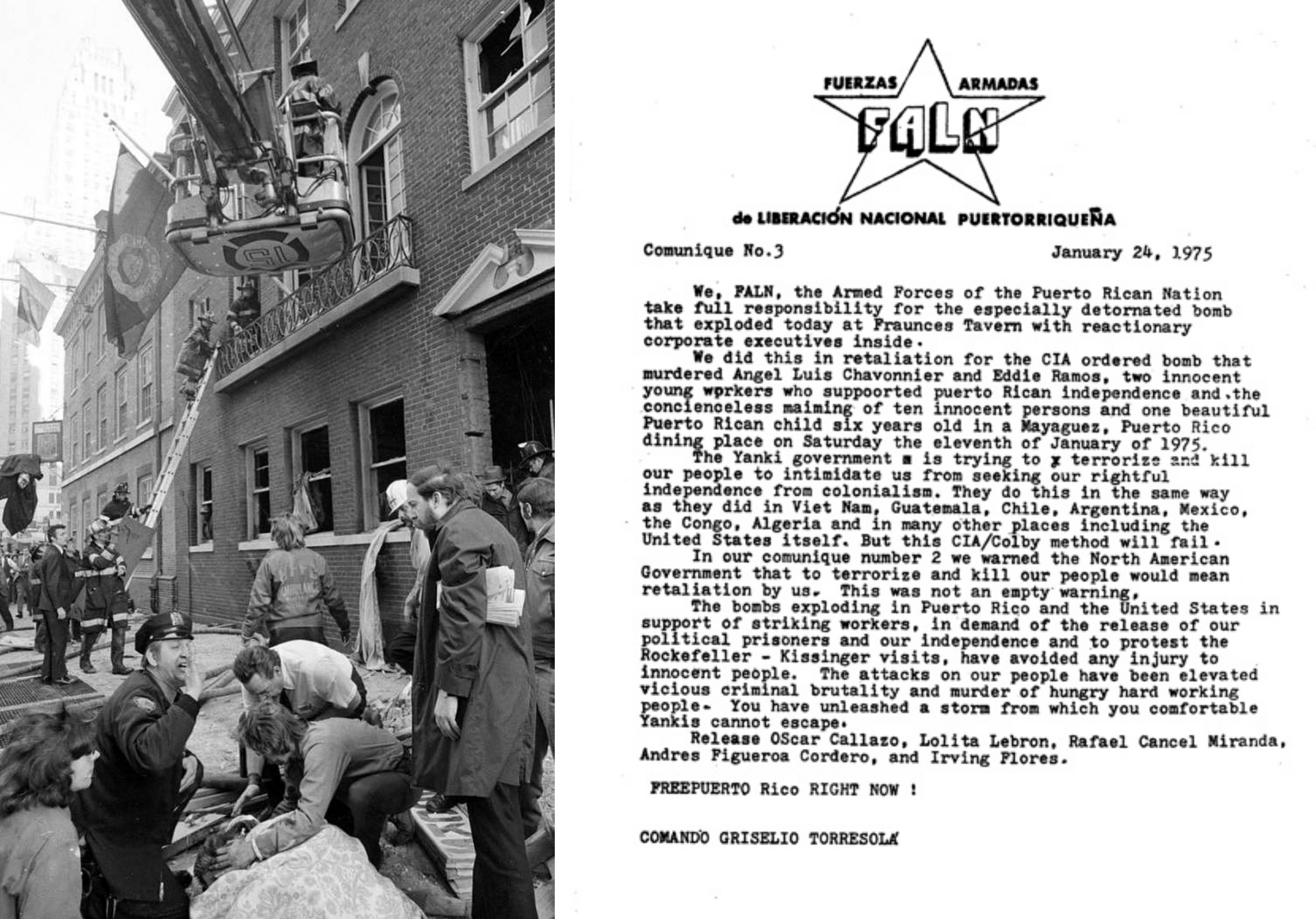

Site of the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN) bombing of Fraunces Tavern in New York City on January 24, 1975 (left) (Photo by Harry Hamburg/New York Daily News), and a communique in which FALN members take responsibility for the bombing (right).

Nationalist opposition to United States federal governance formalized in the 1970s. The Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN, Armed Forces of National Liberation) officially emerged in the United States after the group claimed responsibility for detonating five bombs in Manhattan on October 26, 1974. The next year, the FALN took credit for a series of bombings in New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. Nine people were killed and at least 50 more wounded.

The main goal of the FALN was complete independence for Puerto Rico. In 1999, President Bill Clinton granted clemency to 14 convicted FALN members who had been imprisoned for a variety of reasons—though none of those released were involved in the bombings. This was a highly controversial decision condemned by Congress and, as it happens, by then Senate-hopeful Hillary Clinton.

8. Problems in Puerto Rico: Vieques Naval Base

The Vieques Naval Training Range was a United States Naval base on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques with a permanent military presence from 1941-2003. One of the primary purposes for the base was bomb and missile-launch training. The range was temporarily closed in 1999 following an incident where a Marine Corps F-18 mission dropped two bombs too close to a security post, killing Puerto Rican civilian employee David Rodríguez and injuring four others. This incident spurred a protest against the use of the island as a bombing range. That protest gained international attention and support from a variety of people including pop star Ricky Martin, Al Sharpton, and even Pope John Paul II.

The protests and international pressure prompted President Clinton and later, President Bush, to work with Puerto Rican governor, Pedro Rosselló, to decide whether the base should remain open. In June 2001, President Bush assured the residents of Vieques that the United States military presence would end by 2003. However, the May 1, 2003 withdrawal of military troops was not the end of the controversy. Environmental damage and health problems have been linked to the operations and pollution of the base activities, resulting in lawsuits in some cases.

9. Barack Obama Has a Statue in Puerto Rico

A statue of former President Barack Obama installed in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 2012.

On June 14, 2011, President Obama became the first sitting United States president to visit Puerto Rico since President Kennedy’s trip in 1961. Just shy of 18 months out from the 2012 election, many questioned if the visit was a political move for a second term, reaching not only voters on the island, but appealing to Puerto Ricans living on the mainland. This was especially relevant in the battleground state of Florida, which at the time of his visit, was home to nearly 850,000 Puerto Ricans.

Regardless of his motivation, the President’s trip reminded the world that Puerto Rico was not forgotten. During his administration, President Obama ramped up efforts to bolster economic growth in Puerto Rico, especially with the 2016 signing of the bipartisan Promesa (“Promise”) bill addressing Puerto Rico’s massive $70 million debt and allowing time to renegotiate its repayment process, earning him a statue on the Avenue of Heroes in San Juan.

10. Irma, Maria, and Donald, Oh My!

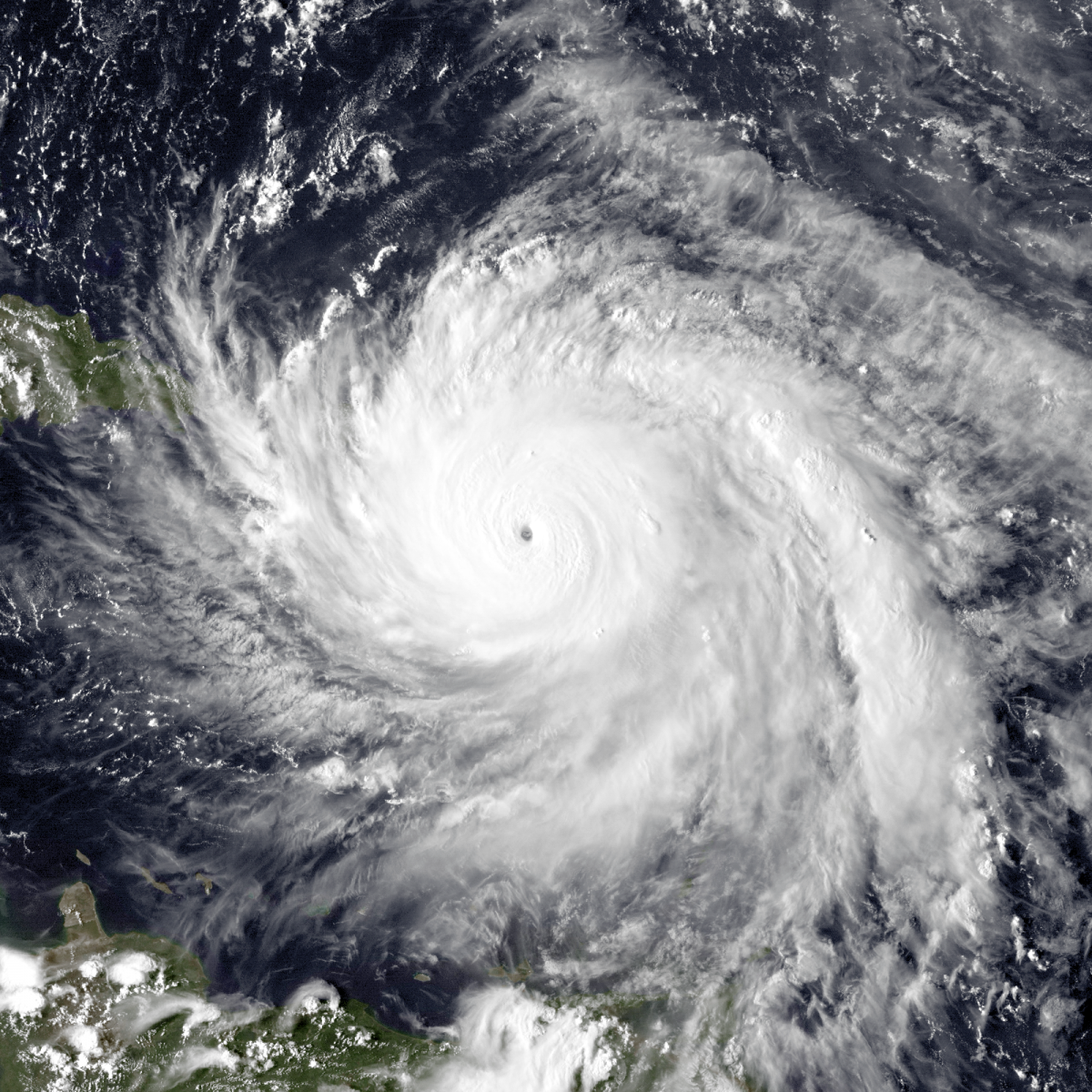

Satellite image of Hurricane Maria moving towards Puerto Rico on September 19, 2017.

Ten major hurricanes have damaged Puerto Rico since it became a United States territory in 1898. Three of these have hit the island in the past twenty years, each with varying levels of devastation. Hurricane Georges (1998) left 700,000 Puerto Ricans without water and one million without electricity, causing about $2 billion in damage. President Clinton sent emergency relief workers as well as scouts to report what further action was needed.

Hurricane Irma hit two weeks before Hurricane Maria, ravaging Puerto Rico in August and September 2017, respectively. These two storms left between 500-1,000 dead from the hurricanes and their after-effects, created an estimated $90 billion in damage, and left 3.4 million people without power.

The Trump administration’s underwhelming response generated emotionally-charged and polarized public reactions. On one hand, President Trump pledged support for clean-up before Maria made landfall, sent roughly 3,200 staffers to Puerto Rico for recovery efforts, and himself traveled to San Juan in early October to help distribute food and hygiene products. On the other hand, when the Puerto Rican government voiced complaints over insufficient aid, the President used the opportunity to call out Puerto Rico’s high debt and criticize its leadership. As of February 16, 2018, nearly half a million people were still without power.