Susannah Heschel is the daughter of the Jewish theologian Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. Aryan Jesus is in many respects the historical counterpart of Abraham Heschel's book, the Prophets. As Susannah notes in the introduction to that book, her father, having gotten his doctoral degree in Germany during the 1930s was in part responding to currents within German Protestantism that sought to move against the Old Testament and remove any Jewish element from Christianity.

The Prophets is a ringing defense of the continued relevance of the Old Testament and is unapologetic about its very Jewish character. Like much of Abraham Heschel's work, the Prophets was written not for a Jewish audience but for people of faith in general. Writing during the era before Vatican II, Abraham Heschel was challenging his Christian readers to confront Judaism as a living organism and not simply as a relic of the Old Testament and to look in on their own Christianity as something very Jewish.

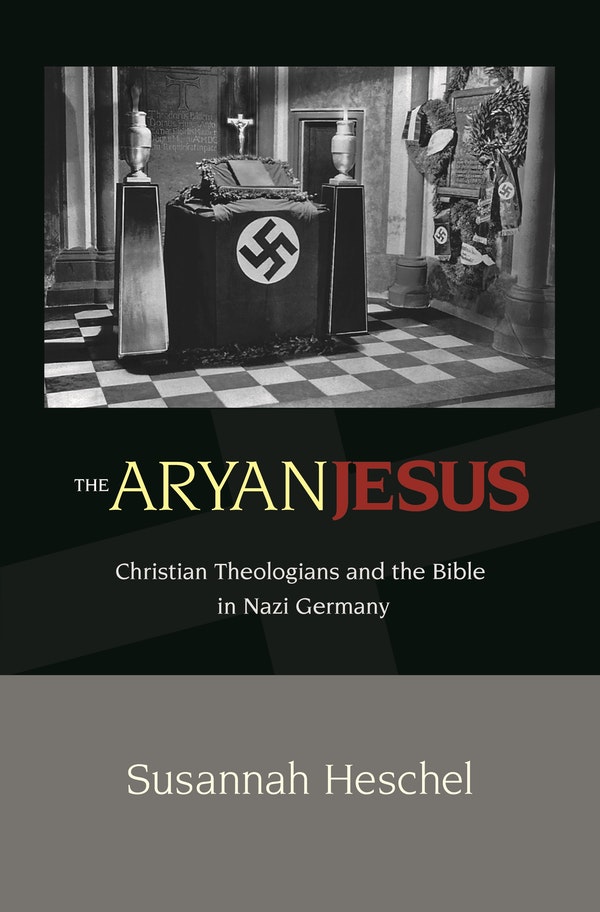

Susannah Heschel seeks to bring out this pro-Nazi Protestant German Christianity, which her father had to confront as a young man, from the obscurity of the archives. She focuses her attention on the Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life, essentially a German Christian think tank that operated during the war, and on its head Walter Grundmann, a New Testament scholar and professor at the University of Jena. This is then used as a window into the wider world of German Christianity.

Being a German Christian and accepting Nazi anti Semitism and racial ideology required one to overcome a number of intellectual hurdles. How could one accept Nazi claims of Jewish inferiority if Jesus himself was Jewish? How can one reconcile Nazi claims of a German master race with Christian universalism? What should be done to the Old Testament, a Jewish book?

To clear these hurdles German Christians insisted that Jesus was not really Jewish, but someone who fought against Judaism. Jesus was the Son of God so he was free of any Jewish biological taint. Alternatively, many argued that the Galileans were really genetic Aryans as opposed to the Judeans, who were genetic Jews. So the Jewish Judeans crucified the Aryan Jesus as part of their racial war against Aryans. Just as God created a hierarchal order in creation so too did he create a hierarchy in races. The Christian spirit finds its ultimate expression within the Aryan race. Many German Christians wanted to get rid of the Old Testament altogether. The real source of Christian values for them was not Judaism and the Old Testament but "Aryan" religions such as Zoroastrianism and Buddhism.

As a work of intellectual and social history Aryan Jesus is quite remarkable. Meticulously researched, Aryan Jesus manages to capture the intellectual milieu of Nazi Germany, offering a fascinating glimpse into academic culture under Nazi rule. As with all good intellectual history, Aryan Jesus succeeds at presenting and analyzing ideas, even offensive ideas, without polemic or judgment. Grundmann and his colleagues may have been anti Semites, racists and bigots, but that is incidental to this work. For Susannah Heschel they were scholars living under Nazi rule and products of nineteenth and twentieth century German Protestant scholarship and racial theory.

While Aryan Jesus first rate as historical analysis, it does suffer from the lack of a clear argument and thesis. The problem, I suspect, is that Susannah Heschel found herself unable to write the book that she really wanted to write. One gets the sense that Susannah Heschel wanted to write about Christian responsibility for Nazism and the Holocaust. She was unable to write such a book because the evidence for such claims is scant and indirect.

While one can easily see how the Institute might have been useful in justifying the annihilation of Jews, there is no direct link between the Institute and the Final Solution. While Grundmann and his circle saw themselves as part of a Germanic tradition of anti Judaism that included Martin Luther, it is very clear that they were products of nineteenth and twentieth century German scholarship, something quite distinct from the Middle Ages or even Luther.

German Christianity did not equal Nazism. While the Nazis were willing to use German Christianity to further their own aims, we do not see any heartfelt support or identification with their Protestant ideology. There was even a law passed banning the use of swastikas in churches. The dominant attitude toward Christianity displayed by the Nazi leadership was that of Alfred Rosenberg who maintained that Christianity was a Jewish religion. Throughout the years of Nazi rule German Christianity was on the defensive, trying to show that "real" Christianity was diametrically opposed to Judaism. The impression one gets about Grundmann and his circle is that of some geeky misfits in school, vainly pleading to be let in and accepted by the in crowd. They might be tolerated to some extent, mainly out of amusement, but are generally held in contempt.

Susannah Heschel sincerely wants this to be a controversial book that will challenge the consciousness of Christians so she tries to dance around these issues, implying things but making no hard claims. For example, she states:

One cannot prove that the Institute's propaganda helped cause the Holocaust. However, the effort to dejudaize Christianity was also an attempt to erase moral objections to Nazi anti-Semitism. Institute-sponsored research, by describing Jesus's goal as the eradication of Judaism, effectively reframed Nazism as the fulfillment of Christianity. Whether the Nazi killers of Jews were motivated by Institute propaganda cannot be proven, but some did express gratitude for Institution publications, apparently for alleviating a troubled conscience. Institute publications were not as widely disseminated as the propaganda issued by the Reich Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, or the publications of Julius Streicher, who was hanged at Nuremberg for editing Der Sturmer, a weekly anti-Semitic propaganda rag. Yet the moral and societal location of clergy and theologians lends greater weight to the propaganda of the Institute; propaganda coming from the pulpit calls forth far deeper resonance than that spoken by a politician or journalist. (pg. 16-17)

The only time that Susannah Heschel manages to score any serious points is with her discussion of the post-war period, during which time the members of the Institute, by and large, managed to do quite well for themselves. They managed to survive the denazification process in Germany and were accepted back into the fold of mainline Protestantism. How someone like Grundmann managed to be accepted by mainline Protestants after the war, I agree, is a good question and should disturb people.

If I were a conservative Christian, the story that I would see in Aryan Jesus is how a bunch of Christian theologians tried to reinvent Christianity in order to make it conform to the values of the time and place, 1930s Nazi Germany. They turned Christianity on its head, hoping that secularist Nazis would embrace their Christianity. In the end all they did was to serve as useful fools to the secular Nazi regime and failed to do anything for Christianity.