During the past year, Russia’s legacy as an imperial power has suddenly become the stuff of current affairs. As Russian leaders assert the rights of their co-nationals abroad, they have also looked to strengthen ties with (or just annex) former imperial domains, from Crimea to Kazakhstan. Many scholars have analyzed the peculiar dynamics that make up the vast, diverse world of the former Russian Empire and Soviet Union, but few have produced works as engaging and insightful as Willard Sunderland’s book, The Baron’s Cloak.

Centered on one man, the Russian-German noble, Baron Roman Fedorovich von Ungern-Sternberg, Sunderland’s work is a brilliant portrait of the Russian Empire and its collapse in the face of revolution and civil war. With eloquence and wit, The Baron’s Cloak brings a complex historical epoch to life and provides a highly readable primer for anyone seeking to understand the Russian Empire and the legacies of imperial rule across Eurasia.

Why Baron Ungern? An obscure historical figure, Ungern is best known as the “Mad Baron of Mongolia,” a tsarist cavalry officer who led a polyglot army (his so-called “Asiatic Division”) against Bolshevik (Communist) forces in Mongolia and Siberia during the Russian Civil War (1918-1921). In 1920, as the Bolsheviks consolidated their rule in central Russia, Baron Ungern set out from the Mongolian steppes on an ill-fated crusade to defeat the “contagion” of European revolution by restoring the empires of Russia, China, and Mongolia, together with their religious traditions and social hierarchies.

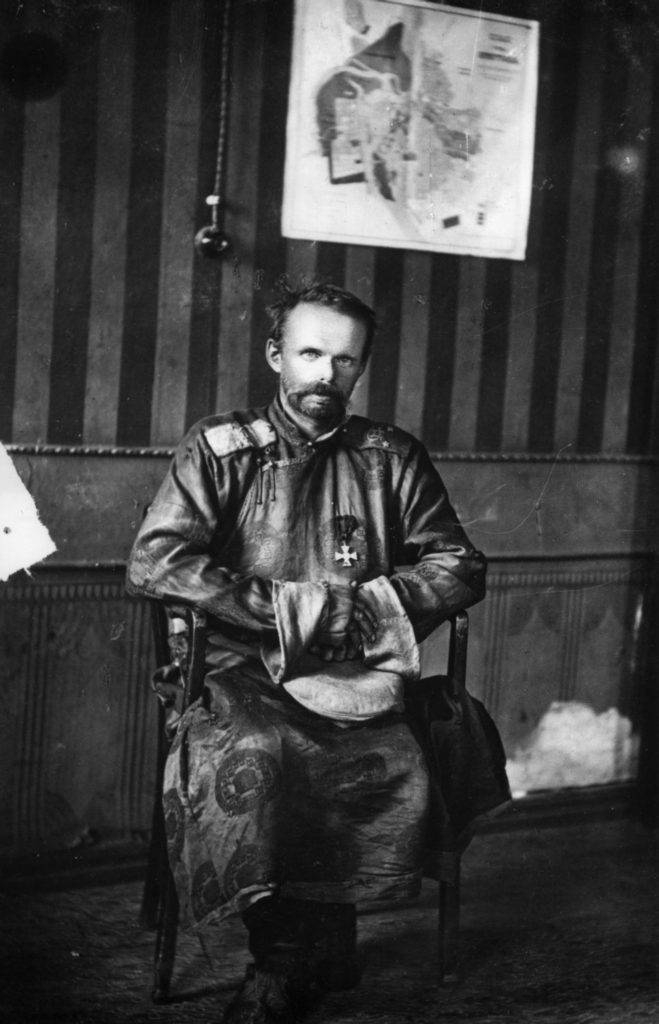

On his campaign, Ungern wore a Mongolian cloak known as a deel adorned with his tsarist army epaulettes and medals. For the Bolsheviks (who captured, tried, and executed him in 1921), the cloak was a testament to the baron’s retrograde, eccentric, and deeply reactionary ideas. It was, in their eyes, a symbol of a past best left abandoned. But as Sunderland shows, the baron’s cloak (and the baron himself) can also serve as a metaphor for the Russian Empire, with its dizzying fusion of cultures, porous frontiers, and the “imperial people” who tied the empire together.

The concept of Ungern as an “imperial person” lies at the heart of Sunderland’s work. It is not, however, a biography, but rather a microhistory that uses Ungern’s life as a lens through which to view the Russian Empire in a time of great flux. The author argues that a focus on “imperial people” like Ungern offers a different view than that offered by typical histories of empire. Not only should we focus on the differences that divided multiethnic empires, he contends, but also how disparate regions fit together in a larger whole, and why they fall apart, and how individual people like Ungern were integral in making the parts fit together in an awkward but ultimately coherent way.

Sunderland traces Ungern’s life from his childhood to his final days during the Civil War. Living first in Austria and Estland (now Estonia) on the Baltic Sea, Ungern grew up in the cosmopolitan, transnational world of the German aristocracy. He came of age in a time of rising nationalism and Russification of the Baltic region, an area that had long enjoyed cultural autonomy. But, as Sunderland points out, people like Ungern could exist in two (or more) worlds without apparent contradiction.

To his German heritage and Russian education Ungern added a deep affinity for eastern cultures acquired during his military service on the frontiers of Siberia and the Russian Far East. Here Ungern served with a Cossack unit (photographed below) stationed in a porous borderland where Russian, Mongol, Chinese, and Manchu cultures intermixed. Unlike many of his contemporaries, who looked with disdain upon their Asian neighbors, Ungern believed that the East represented a world where tradition and order had been preserved, and which could serve as humanity’s salvation from the degeneracy of modern life. From the grasslands of eastern Siberia Sunderland follows Ungern to the battlefields of World War I in Eastern Europe and Persia, and finally to Ungern’s fateful involvement with the White (anti-Bolshevik) armies in Siberia and Mongolia.

Few documents on (or by) Ungern exist, except those dealing with his Mongolian Campaign and trial in Bolshevik-controlled Siberia. As a result, Sunderland must infer much of what the baron experienced from a broad array of indirect evidence and a reconstruction of the historical context. The lack of clear information can be frustrating at times, but on the whole it is an impressive piece of scholarship. Sunderland does an admirable job of triangulating the baron’s life and thoughts from primary and secondary sources (in five languages), and he creates a rich historical tableau built around Ungern, rather than a biography about him. Moreover, by foregrounding the uncertainties of his research and the challenges of historical study more generally, Sunderland involves the reader in the task of discovering Ungern and the world he inhabited.

Besides being an entertaining story, The Baron’s Cloak has much to interest both scholars of Russia and the general reader. Sunderland’s writing is a model of concision and erudition. He seamlessly integrates mountains of scholarship on the Russian Empire and Civil War, bringing wide-ranging historical works together in a way that is engaging, insightful, and accessible to a wide audience. Along the way he neatly summarizes critical moments in Russian history, from the conquest of Siberia to the Civil War, incorporating these events into a cohesive and focused narrative.

The book is striking in its contrasts. It focuses on the life of one man, but provides a synoptic view of the Russian Empire in its twilight. It highlights the way that cosmopolitan nobles like Ungern moved effortlessly through an immense, diverse landscape, but also gives the reader a powerful sense of place, from aristocratic Graz (Austria) and to the arid steppes of Mongolia. Sunderland shows the creative energy of one space in particular—the Eurasian frontier—in juxtaposition to the development of modern statehood, fixed borders, and citizenship, a trend that, he argues, was not unidirectional or inevitable.

The book is, in a sense, a story of the passing of two “frontiers,” the physical and the personal. One was characterized by the mixing of diverse peoples, the other by the mixing of cultures in a single person. The result is both a paean for a lost world and an engrossing account that shows in vivid detail the lived experience of an imperial servitor in the Russian Empire’s final years. Not only did Ungern serve the empire, Sunderland contends, he embodied it, bore witness to its unraveling, and was a casualty of its new incarnation, the Soviet Union.

As Sunderland’s account makes clear, the lines between historical epochs are seldom so clear to those who lived through them. In documenting Ungern’s life and times, Sunderland reveals the strange and unpredictable coexistence of imperial rule in the age of nationalism, a coexistence that proved remarkably durable in the 20th century and which reverberates into our own times.