The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley, 5000-3500BC is the second international loan exhibit organized by the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University. The exhibit ran through April 25, 2010, and the objects on display are appearing in the United States for the first time. (http://isaw.nyu.edu//exhibitions/oldeurope/introduction.html).

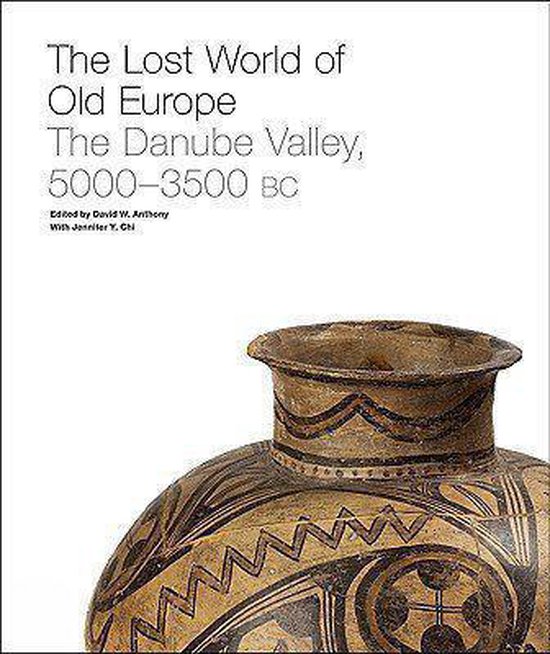

It is a collaborative project between the Institute and over 20 museums in Romania, Bulgaria and Moldova, the heartland of Old Europe during the Copper Age. The book under review here is the published catalogue for this exhibit, and it features stimulating thematic essays by leading experts in the field as well as abundant (and striking) color photographs of the exhibit's objects.

The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World is a unique organization that promotes the cross-cultural study of antiquity across the whole of the Old World. It also maintains a commitment to the study of the ancient world from the perspective of peoples and civilizations that are often omitted (or marginalized) in traditional research programs. The Institute certainly succeeds in its goal of questioning the "preexisting and sometimes static notions of the ancient world" and showing that a "rich and complex world can be found when looking beyond traditional and narrow definitions of antiquity" through this exhibit. (p. 20)

The book is arranged as a series of thematic studies, each of which touches on a topic of central importance to the study of Old Europe. Every chapter embeds pictures of the exhibit's objects alongside the text but there are many pictures included in addition to these of the region's landscape, excavation records and field pictures, site plans, reconstructions of houses, as well as helpful charts and maps.

The volume begins with David Anthony's overview of the "Rise and Fall of Old Europe," in which he discusses the major categories of evidence for Old European civilization (houses, ceramics, copper implements, figurines, spondylus shells, and graves) and the current debates surrounding them. Since much of this evidence and the basic chronology of Old Europe are likely to be uncharted waters for most readers, Anthony's chapter serves as a necessary gateway to the rest of the book.

The second chapter presents a brief history of archaeology in Romania, whose roots as an academic discipline stretch across the last forty years of the nineteenth century. The chapter includes many interesting pictures of early twentieth century archaeologists, their excavations and records. Among these is one of the German archaeologist Hubert Schmidt, whose excavations at Cucteni in 1909 and 1910, the authors note, are typically regarded as the "beginning of systematic archaeological research in Romania." (p. 59). It concludes with a helpful chronological chart of major excavations related to Old Europe that have been undertaken on Romanian soil over the last one hundred years.

Chapter three, "Houses, Households, Villages and Proto-Cities in Southeastern Europe" by John Chapman, presents an overview of Copper Age settlement patterns, with special attention paid to the uniformity in domestic architecture. The homes of chiefs (and other elites), the author notes, "cannot easily be identified by archaeologists," (p. 85) and it seems that the house was not deemed an appropriate location for displays of social differentiation (as opposed to cemeteries, e.g. at Varna, where social differentiation through grave goods is obvious). Dragomir Nicolae Popovici continues this line of inquiry in chapter four, "Copper Age Traditions North of the Danube River," and provides a broad overview of the "concepts and behaviors of various Neolithic and Copper Age communities." (p. 105)

Douglas Bailey, "The Figurines of Old Europe," discusses the famous female figurines discovered throughout Old Europe. He rejects (quite strongly) the mainstream argument put forward by Marija Gimbutas that the figurines represent cult objects (and deities in Old Europe's pantheon) that functioned in ritual contexts associated with reproduction and death (concerning plants, animals and people). Gimbutas argued further that due to the prevalence of female figurines (the overwhelming majority are female) Old European society was matriarchal. In her view this goddess-centered culture was swept away when patriarchal Indo-Europeans arrived and conquered the region. Indeed, when glancing at the many photos of these figurines in this chapter it is easy to understand why their function and meaning remain hotly contested. But they have played a major role in historical interpretations of prehistoric societies and the movements of peoples (e.g., Indo-Europeans) well beyond Old Europe.

The next three chapters deal with technology (ceramics and metallurgy) and trade (spondylus shells) in Old Europe. Lavarovici's chapter on Cucuteni ceramics is the fullest in the entire book (text and photos) and contains an excellent overview of the technology of pottery production in Old Europe (clays and kilns), its shapes and the decorative patterns painted or incised onto the pots. Enrst Pernicka and David Anthony discuss copper metallurgy in Old Europe. The metal artisans of Old Europe were highly advanced and produced a tremendous amount of copper implements. Artifacts recovered by archaeologists to date total 4,700 kilograms of copper and over 6 kilograms of gold, which is a total greater than any other found anywhere in the ancient world before 3500 BC (p. 29). The implications of the origins of copper smelting are also addressed. At present, the chronologies between the Near East and Old Europe are strikingly close, enough so that we could be dealing with independent metallurgic advances in both of these regions rather than diffusion from the Near East to Europe. The final two chapters detail the finds from two cemeteries, including Varna, mentioned above. Its graves contain "stunning quantities of gold" (p. 193) and constitute the oldest known example of humans interred with "abundant gold ornaments." (p. 193) The book concludes with a list of participating museums (p. 226), an exhibit "checklist" (pp. 228-239), and lengthy bibliography (pp. 240-252) for any eager readers.

This book provides a comprehensive introduction to Old Europe's cultural legacy and also demonstrates that Old Europe deserves a more prominent place in our understanding of the development of early civilizations, whether due to its metallurgic or ceramic technology or its female figurines. The writing is lucid and done by experts who are conversant with the major ongoing debates in the field today and the layout is exemplary. The color photographs are plentiful and any reader can, in a sense, study the objects directly while reading the text. Anyone with an interest in learning about a burgeoning field in European prehistory—and rethinking some assumptions and conclusions about the development of civilization in the West—would enjoy this book.