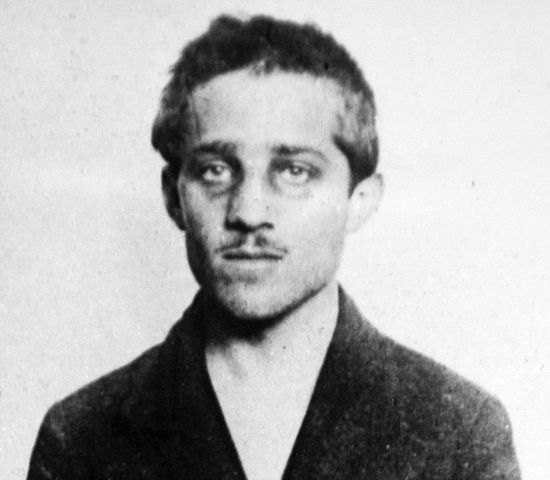

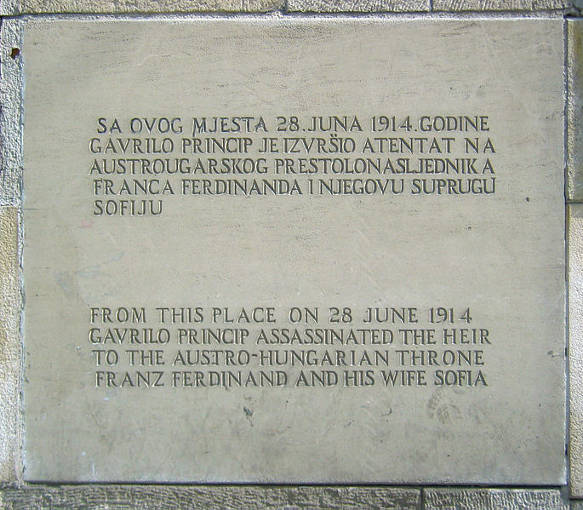

On June 28, 1914, one event changed the world. A Bosnian-Serb youth Gavrilo Princip, aged only 19, shot and killed the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir apparent to the Austrian throne, and his wife Sophie as their motorcade passed by on the streets of Sarajevo. Princip was promptly arrested and imprisoned, where he would die of tuberculosis in 1918.

But while the assassin’s fate was settled quickly, the deaths of his prey were the trigger that began the First World War. A cascade of diplomatic alliances among Europe’s great powers quickly drew almost the entire European continent, and ultimately the world, into a conflict that would cost nearly 15 million lives and change the face of the planet for generations to come.

Legend tells that shortly before his death in prison, Princip inscribed a warning on the walls of his cell: “Our shadows will walk through Vienna, wander the court, frighten the lords.” In 2014, as preparations in Sarajevo were underway for the centennial anniversary of the assassination, his warning proved apt. Event organizers struggled to navigate not only his personal story and the immediate legacies of his actions, but also the various interpretations and ideological positions that coopted the meaning of his short life over the following century.

The assassination itself was the realization of a plot by a youth group called Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia), populated mostly by Serb students dedicated to ending the Austro-Hungarian occupation in Bosnia-Herzegovina that had begun in 1878. By 1914, several independent states had already emerged in the Balkans, including a free Serbia. It was Princip’s and Mlada Bosna’s ultimate ambition not only to liberate Bosnia-Herzegovina, but to realize its inclusion into a larger, independent South Slav state with Serbia and other South Slavic peoples.

As plots go, the assassination was one of the most successful ever conceived. By its end, World War I helped to bring on the collapse of the four East European empires (Austro-Hungarian, German, Russian, and Ottoman), and the establishment of a number of new nation-states, including the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. There, Princip was hailed as a national hero who had unified the South Slavs and freed them from foreign rule.

But as the political landscape of Europe changed, so too did the ways that Princip’s legacy was discussed and understood. In post-World War II Yugoslavia, he came to embody the values of socialism, becoming a people’s hero of anti-imperialism who had liberated the masses from Austro-Hungarian oppression and exploitation.

The violent breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s recast Princip’s legacy yet again, this time in the context of ethnic conflict. In the wake of ethnic cleansing, it became common among Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) to interpret Princip in a way that spoke to their recent experiences of ethnic violence. In particular, they reflected on his call for South Slav unification as a thin veil for Greater Serbian ambitions and his affiliations with militant Serbian extremist groups (such as the Black Hand or Unification or Death (Ujedinjenje ili smrt) as evidence of the violent ends towards which they were prepared to go to reach their goals.

Conversely, Bosnian Serbs have largely continued to venerate Princip as a hero, but his devotees have increasingly portrayed the 1914 assassination as an act of national defense against those who intended to divide the South Slav peoples.

Nearly thirty years of regional ethnic politics since the breakup of Yugoslavia have ensured that Princip’s legacy has now been firmly caste along ethnic lines. As a result, preparations for the 100th-year anniversary in 2014 were quite a heated affair.

Acutely aware that the centennial had become a prism through which more recent events were being debated, official planners expressed their commitment to combat yet another of Princip’s legacies—the perception of the Balkans as a hotbed of nationalism and the volatile “tinderbox of Europe.”

Graffiti memorializing Princip in Belgrade near the central train and bus stations, ca. 2011.

To challenge this view, Sarajevo planners (in cooperation with various EU organizations) endeavored to diffuse tensions about the past by holding a variety of events geared towards promoting peace in the future, including art exhibitions and unveilings, sporting events, and youth activities.

But while organizers claimed to present a forward-looking “global message of peace,” the events themselves showed how difficult it was to separate the commemorations of 1914 from more recent events. A number of photo exhibits featured work by war photographers dating from 1992-5, and the keynote performance by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra was presented in Vijećnica, the city hall that was burned down in the 1990s and reopened only in May of 2014.

Over the course of the twentieth century, Princip’s shadow indeed wandered, his legacy becoming more a symbol than history—appropriated and mythologized, coopted and codified to reflect a variety of political persuasions, ideologies, and allegiances.

Perhaps Princip’s strongest legacy then has been that he has served as a reflection of our contemporary preoccupations. But whether it is Princip the terrorist or Princip the great defender, the truth is lost in the political rhetoric.