Europeans are certainly familiar with national borders. Across the 20th century borders have been fought over, drawn and redrawn, and today the “integrity” of those borders in the face of migration and refugees is perhaps the biggest issue tearing at the fabric of European union. Europeans might be less familiar with the concept of “borderlands,” however. This is an analytic concept historians have used, especially when examining the American West, certain parts of Africa and other places where borders don’t function as a hard separation but as places of cultural interaction. Borders divide; borderlands mix things up.

Historian Eagle Glassheim brings the analytic frame of “borderlands” to craft a new conception of the Sudetenland, that space in between Germany and Czechoslovakia. Glassheim recognizes the challenge of bringing this idea developed to understand the colonization of the American West in the 18th and 19th centuries to the study of Czechoslovakia after the Second World War. Glassheim notes that with the end of combat in Europe in 1945, the borderlands of Czechoslovakia were “certainly not the lively ‘contact zones,’ ‘crossroads,’ and ‘fluid transitional spaces’ associated with scholarship on North American border regions.” He also acknowledges that with the onset of the Cold War the borderland was more powerfully divided and less easily traversed. Still, thinking of the Sudetenland as a borderland gives us a new way of looking at this fraught piece of geography.

For Czechs and Slovaks after the war, the Sudetenland became something of a tabula rasa whereupon their aspirations for the future and their conception of the past could be written. An important prerequisite had to be met, however, in order for this land to serve the Czechoslovakian peoples in such a way – the deportation of nearly two million Germans out of Czechoslovakia and into the now divided German state. As a result, according to Glassheim, Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland is a "modern borderland," that is, a now "cleansed" former contact zone.

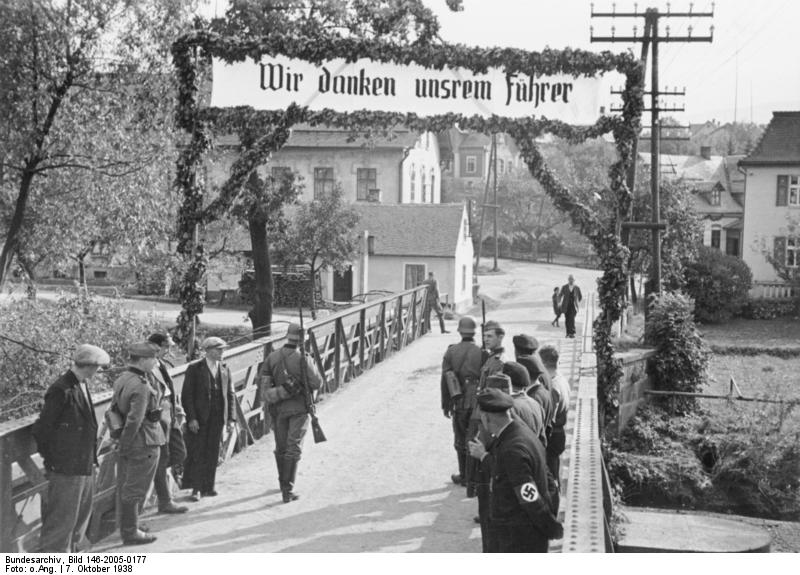

In the opening chapters of the book, Glassheim recounts the long history of German and Czechoslovakian competition to define the Sudetenland each in its own in nationalistic terms. German expansion into the region settled the question during World War II. After the war, the Czechoslovaks returned the favor. Between 1945 and 1947, Czechoslovakian authorities sought to de-Germanize and homogenize their nation. In so doing, the Czechoslovakian Sudetenland was emptied of its “foreign” inhabitants, and this allowed for Czech reclamation of the region. Glassheim’s discussion of the redevelopment of the borderlands after the expulsion of the Germans is particularly important. He demonstrates that this process was a political, environmental, and medical one.

The most valuable contribution of Glassheim’s work is his incorporation of environmental and medical history into his analysis of the Sudetenland. Environmentally, Glassheim intertwines the visions of grandeur that Czechoslovakian officials had for the newly repurposed and reconsolidated Sudetenland with the industrialization of the region during what Glassheim labels as “high modernism.” It was the borderland that served as the natural starting place for this new boom in modernization and industrialization, as evidenced in Glassheim’s chapter on the Czechoslovakian town of Most which he labels as the ground zero of postwar borderlands transformation in Czechoslovakia.

Most, “the town that moved,” best instantiates the multiple arguments about borderlands, health, and environment that Glassheim centers his book on. After the Second World War, the mass deportations of Germans from Czechoslovakia, and the Communist ascendancy in 1948, the town of Most, which had been 64% ethnically German, transformed into an almost completely ethnically Czech mining complex. So vast was the mining pit that emerged in Most that the entire town was transplanted to a new location. The only building that survived was a church that was transported by rail to a new location. The borderland had transformed from a German space to a Czech one and from an historic setting to an industrial one.

But it was not just notions of industry that concerned Czech officials. The language of public health played a central role in the re-creation of Most. Glassheim quotes Czechoslovak minister of justice Prokop Drtina referring to Germans in Czechoslovakia as “always a foreign ulcer in our body.” That "ulcer" was remedied in Most by way of a forced “cleansing” or “liquidation” of Germans forcing them abroad to Soviet and American occupied Germany. In a more concrete sense, Glassheim demonstrates that medical language was also used in an effort to homogenize the borderlands by casting marginal peoples such as Gypsies and Germans as carriers of disease. Such rhetoric made the issue of resettlement of the Sudetenland and the ethnic cleansing of Czechoslovakia not only a political consideration, but also a medical one.

Ultimately, Glassheim remarks that historians ought to find a way to bridge the two national narratives about the Sudetenland: the German story of displacement and loss, and the Czech story of cleansing and reclamation. Doing so, he suggests, would turn this borderland into a place of community building and healing. Glassheim argues that if historians produce meaningful two-way histories that discuss both the history of this borderland as a German and Czechoslovakian space that they can help to mend the memory of this borderland between these manifold groups. Ultimately, Glassheim argues, “to heal the borderlands is to heal ourselves."