On August 7, 1998, Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda organization bombed American embassies in Nairobi, Kenya and Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. The attacks utilized massive truck bombs that nearly destroyed the embassies and devastated the surrounding neighborhoods. The bombings ultimately killed 224 people and injured many thousands more.

The attacks marked a dramatic escalation in al Qaeda’s self-declared war against the United States. Although the group had been involved in numerous terrorist attacks around the world, prior to that point it had not attacked America or its citizens directly. Officials in both the FBI and the CIA were tracking the organization, but at the time it seemed like a relatively minor threat in comparison with established groups like Hamas and Hizballah.

Bin Laden had already escalated his rhetorical war against America the previous February, when he published a fatwa (religious edict), on behalf of a coalition of militant groups called The International Islamic Front for Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders.

The document amounted to a declaration of war and formally united a half-dozen different militant groups in Afghanistan in opposition to America. Ominously, the document declared: “The ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilian and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it.”

The date of the operation was symbolic—August 7, 1998 was the 8-year anniversary of the arrival of American troops in Saudi Arabia in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. And the attack was executed in a manner that would soon come to characterize al Qaeda operations.

The trucks were both driven by suicide attackers and the bombs were delivered only a few minutes apart, beginning with the first blast in Nairobi at approximately 10:35 local time. Each of the truck bombs contained more than a ton of explosives.

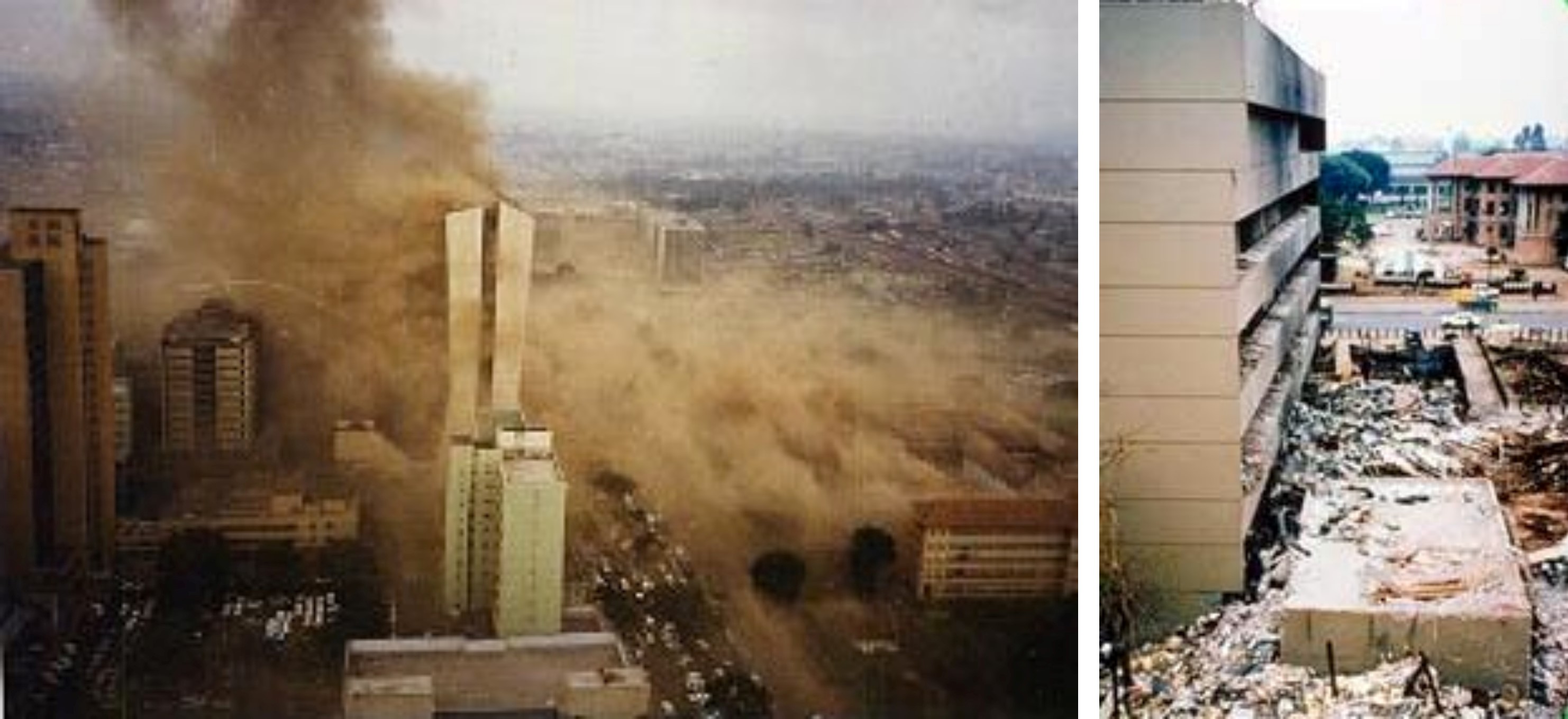

In Nairobi, the blast sheared off the face of the embassy and completely destroyed a neighboring seven-story office building that contained a secretarial college. The toll was 213 dead, among them 12 Americans. Hundreds of people were blinded by flying glass and it took rescuers two days to free all the people buried in the rubble and debris.

As deadly as the attacks were, they could have been worse. In Nairobi an accomplice to the suicide bomber failed in his task of raising the drop bar that prevented entry into the embassy parking lot. Because of his failure the bomber was unable to get his vehicle close enough to destroy the building entirely.

Aerial view of the embassy bomb blast in Nairobi, Kenya (left), and the aftermath of the 1998 bombing (right).

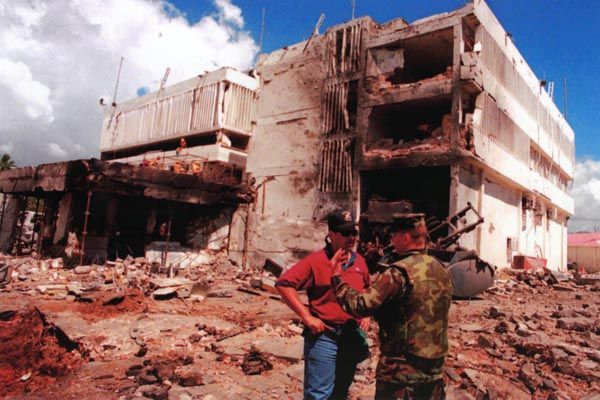

A view of the damaged U.S. embassy in Nairobi, Kenya.

A U.S. FBI agent sorts through rubble. (Photo by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation)

In Dar-es-Salaam, a water truck was parked near the embassy, blocking access and absorbing much of the force of the blast. This lucky coincidence, coupled with the fact that the embassy was located in a sparsely populated area, resulted in a much lower human cost—11 people were killed and 85 wounded.

All of the victims in Dar-es-Salaam were African, as were most of the victims in Nairobi. The attack therefore inflicted far greater harm on civilians—many of whom were Muslim—from two African nations than it did on the Americans against whom it was supposedly directed. This type of outcome has characterized al Qaeda’s operations in the years since, with the group now responsible for the deaths of thousands of Muslims in North Africa, the Middle East, and Southwest Asia.

The U.S. embassy in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania following the 1998 bombing.

At the time of the attacks, the Presidency of Bill Clinton was mired in the Monica Lewinsky sex scandal. The government’s response to the attacks was therefore limited to a terribly counter-productive set of cruise missile strikes, ironically dubbed Operation Infinite Reach, launched against targets in Sudan and Afghanistan on August 20.

In Sudan, the United States used thirteen Tomahawk cruise missiles to destroy a pharmaceutical plant that was supposedly producing a chemical precursor for VX nerve agent. The plant instead turned out to be a legitimate factory that produced nearly half of Sudan’s medicines and had no connection to Osama bin Laden.

In Afghanistan, sixty-six US missiles were targeted against training camp facilities associated with bin Laden. Neither bin Laden nor his second in command, Ayman al Zawahiri, was in the area, however, and both escaped unharmed. The missiles destroyed several buildings in the camp and killed six men, none of them al Qaeda leaders. Many of the missiles exploded just across the border in Pakistan.

The Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Sudan after the U.S. missile attack (left), and a satellite image of the Zhawar Kili Al-Badr training camp complex in Afghanistan (right).

The American response unintentionally strengthened the alliance between al Qaeda and the Taliban, bin Laden’s hosts in Afghanistan. Prior to the missile strike, Mullah Muhammad Omar, leader of the Taliban, had promised to hand bin Laden over to Saudi Arabian officials, which would have ended his terrorist career. After American missiles exploded in Afghanistan, however, such an act would have seemed like giving in to American pressure, so Mullah Omar reneged and instead continued to provide bin Laden with sanctuary.

The most troubling legacy of the failure of Operation Infinite Reach was that bin Laden’s defiant survival established him as a symbolic figure of resistance against the United States. Prior to the bombings and the American response, bin Laden had been a relatively insignificant figure in the world of jihad. After August 1998 he became a celebrity militant, bringing al Qaeda prestige and a steady stream of recruits.

A mourner prays at the 1998 bombing memorial in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo by DEMOSH)

Before the embassy bombings, the American counterterrorism community had been divided against itself, with competition and infighting between the CIA and the FBI hampering the ability of both to understand and deal with the threat posed by al Qaeda. The embassy bombings did little to change this, unfortunately, and so efforts to deal with al Qaeda and prevent future attacks continued to be ineffective.

The Clinton administration continued to obsess about terrorists acquiring chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons and therefore underestimated the danger posed by simpler terrorist tactics like suicide attackers.

In early 2001, when the Bush administration took office national security officials were slow to realize how profoundly the threat of jihadi terrorism had grown and did not prioritize it appropriately at first. Consequently, the United States was still vulnerable to jihadi terrorism on September 11, 2001, more than three years after the East Africa Embassy bombings.

Memorial garden in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency)

A memorial sculpture in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania.

Further Reading:

On al Qaeda and the Embassy Bombings:

The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. Authorized Edition. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2004.

Byman, Daniel. Al Qaeda, the Islamic State, and the Global Jihadist Movement: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2015

Wright, Lawrence. The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf, 2006.

On American Counterterrorism Prior to the 9/11 Attacks:

Naftali, Timothy. Blind Spot: The Secret History of American Counterterrorism. New York: Basic Books, 2005.

On Suicide Bombing:

Lewis, Jeffrey. The Business of Martyrdom: A History of Suicide Bombing. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2012.