“Alas, poor world, what treasure hast thou lost!” (Venus & Adonis)

The Globe Theatre burned to the ground on June 29, 1613, during a performance of Shakespeare’s last history play Henry VIII: Or, All is True. A volatile combination of a cheap roof and pyrotechnic effects could have doomed the Globe forever.

Thanks to the literary immortality that Shakespeare achieved but could not have anticipated, the Globe has continually been reimagined and rebuilt, remaining a place of fascination today. As we remember this event 400 years later, the metanarrative of the Globe’s history takes on the qualities of a Shakespearean romance.

Several of Shakespeare’s last works, written in the years preceding the burning of the Globe, are romances that revolve around motifs of loss, recovery, and resurrection. In The Winter’s Tale, a jealous husband, Leontes, accuses his pregnant wife of adultery with his dearest friend. He renounces his friend, sends away his infant daughter to a foreign land, and his wife and young son both perish from grief. Sixteen years later, the daughter, Perdita (whose very name means “loss” and whose imagined portrait is pictured below) returns to her father; the wife, Hermia, who did not die, but has been disguised as a statue, is revivified; and the friend forgiven. The son, young Mamillius, however, is dead and lost forever. This could have been the fate of the Globe.

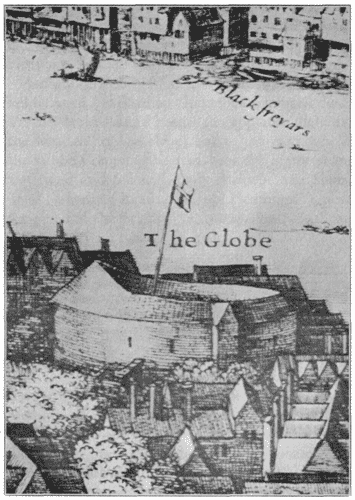

Constructed in 1599, the Globe Theatre had a relatively short, if illustrious and exciting life. A year earlier, the theatre troupe the Chamberlain’s Men lacked a place to perform their plays, including the works of their chief playwright/actor/shareholder, William Shakespeare. The lease had expired on their former home, one of the oldest Elizabethan playhouses, simply named the Theatre. Although recently constructed, the Blackfriars Theatre was not available to the troupe due to a ban on plays in the upscale neighborhood.

In one of the greatest burglaries of all time, in the frigid winter of 1598, the Chamberlain’s Men surreptitiously dismantled the Theatre (the landlord gone for Christmas holidays), labeled all of the parts, moved the pieces of lumber across the Thames, and during spring 1599, reassembled the playhouse in Southwark. This new building was christened the Globe Theatre.

Historian James Shapiro, in A Year in the Life of Shakespeare: 1599, notes that during the rebuilding process, the actor-shareholders suggested architectural changes for improved theatrical effects, but “they’d still have to do it on the cheap: no tiles on the roof, as at the Theatre, just inexpensive (and flammable) thatch.

Shakespeare alludes to the Globe Theatre in several of his works, describing it in the opening passage of Henry V as “this wooden O.” In one of Shakespeare’s last plays, his beloved romance, The Tempest (1611), Prospero abruptly ends his daughter’s wedding masque, claiming, “Our revels are now ended,” and continues “the great globe itself / …shall dissolve” (The Tempest 4.1.148, 153-154). Prospero’s retirement from magic is often read as Shakespeare’s own farewell to the theatre, but Shakespeare could not have known how very prescient his words were.

The destruction of the Globe theatre was never anticipated. Despite a thirty-one year lease in Bankside, the prestigious royal patronage of King James I as the company became the King’s Men, and Shakespeare’s esteemed literary reputation, the Globe Theatre never upgraded its roof.

Sir Henry Wotton described the catastrophe in a letter dated two days after the fire:

The King’s players had a new play, called All Is True, representing some principal pieces of the reign of Henry VIII, which was set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pomp and majesty … Now, King Henry making a masque at the Cardinal Wolsey’s house, and certain chambers being shot off at his entry, some of the paper, or other stuff, wherewith one of them was stopped, did light on the thatch, where being thought at first but an idle smoke, eyes more attentive to the show, it kindled inwardly, and ran round like a train, consuming within less than an hour the whole house to the very grounds.

So, with a match, a cheap roof, and pyrotechnic effects, the Globe Theatre was lost.

The Globe Theatre, however, was not gone forever. It was rebuilt in 1614 (with a tile roof!) and remained a popular playhouse in Bankside until the closing of the theatres in 1642 with the onset of civil war. It was pulled down a few years later in order to make room for cheap housing.

Its foundations were excavated in 1989-1990 by the Museum of London Department of Greater London Archaeology Advisory Service, before being paved over again (now under Anchor Terrace on Southwark Bridge Road). This discovery of the dimensions and shape of the Globe became the blueprint for the current Shakespeare’s Globe (pictured below) located only 750 feet from the original site.

Shakespeare’s Globe opened (or reopened, or even re-reopened) in 1997 with a play about a different historical Henry (and even a mention of fire). Henry V was one of the first of Shakespeare’s plays to be performed at the Globe in 1599. The Prologue of Henry V beautifully describes the Globe Theatre, including its physical limitations, but the ability for the poet’s and the audience’s imaginations to transcend “this wooden O”:

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene! (Henry V Prologue 1.1.1-4)

In Henry VIII: Or, All Is True, the king finds redemption through his infant daughter, Elizabeth, in the final scene of the play. She will be a great queen and England will flourish under her rule. She is likened to a Phoenix, the unique mythological bird: every one thousand years, it builds a nest of fire, self-immolates, and emerges anew from the ashes.

This image is equally fitting for the Globe Theatre—burnt down, rebuilt, demolished, lost, found, and reconstructed—it, too, has reached romantic and mythical status.