While 2018 marked the one-hundredth anniversary of the November Revolution, the debate over what historians have called the failed, incomplete, and even the forgotten revolution has been revived in recent years. Robert Gerwarth’s book November 1918: The German Revolution aims to add to what he calls “a new consensus […] among historians” that we should not look at the Weimar Republic as inevitably doomed. Rather, it should be “explored in an open-ended fashion.” It is an enthralling story.

Gerwarth devotes the first three chapters to the First World War and its effects on domestic and international politics. The next three chapters are dedicated to the events that sparked the November revolution and how they unfolded—from a small sailors' mutiny in Kiel to a full-blown national revolution, including the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm and the proclamation of the German Republic, all in a matter of weeks.

The author next looks at the Armistice negotiations, which reminds the reader that the revolution took place while the Allies hashed out a treaty. The last chapters examine radical movements that tried to derail the establishment of a democratic council and the Versailles Treaty, which challenged the young German Republic.

Gerwarth positions the German Revolution in an international context noting that the revolution was “remarkably bloodless,” at least initially, as compared to other revolutionary regime changes that occurred on the European continent. This was largely due to the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD) and its leader Friedrich Ebert. Ebert rejected a Bolshevik-style revolution stating “I don’t want it. . . I hate it like sin.”

Gerwarth’s ability to put the November Revolution into the context of other socialist revolutions is one of the strongest elements of the book. By doing so, he conveys the sentiment of the moderate and liberal political leaders in Germany who tried to avoid the horrors of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the more recent revolution in Finland.

Ebert and the MSPD decided that a new constitution could only be drawn by a democratically elected national assembly—to the dismay of the Spartacus League, which wanted “a political system in which all power was in the hands of soldiers’ and workers’ councils.” Ebert emerged as Chancellor, which led Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg to form the German Communist Party (KPD).

Until this point, the revolution had remained mostly peaceful. However, following the Christmas Crisis in 1918, and the Spartacist Uprising in January 1919, riots produced some of the bloodiest and most somber days of the German Revolution. They led Chancellor Ebert to call upon German veterans to end the protests.

The short-lived Spartacist Uprising cost the lives of roughly 200 people including those of Liebknecht and Luxemburg. Gerwarth emphasizes that while Ebert and the MSPD thought they “had preserved Germany from Bolshevism,” ignoring the political demands of the KPD and other left-wing parties led to the escalation of conflicts between the military and left-wing militias.

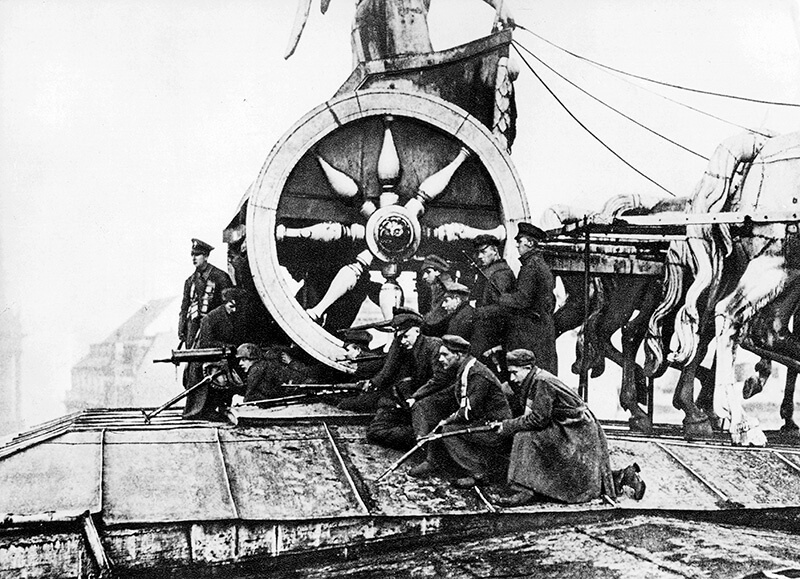

Alert soldiers on the Brandenburg Gate, during the Spartacist Uprising

Despite the elections on 19 January 1919, in which a record number of people went to the polls to vote for the first universally, democratically elected National Assembly, the revolution kept spreading throughout Germany, and it became more radical by the spring of 1919. It aimed to destabilize the parliamentary democracy.

Socialists thought that by making more radical demands, the government would listen and act. Instead, cities such as Munich, long considered more peaceful and liberal, turned to the right. Munich, of course, would become a bastion of Nazism. Here is where we see the notion of a “failed” revolution. Given all this, as Gerwarth explains in the epilogue, it is impressive that the young and “weak” Weimar Republic was able to come out on top of things.

November 1918: The German Revolution is a fascinating narrative of the events that transpired during the time in which Germans called for a more democratic government and more political and social freedom. Throughout the book, the author balances small biographies of important political leaders with the extensive use of newspapers, memoirs, and letters—effectively giving those who lived through the revolution a voice.

Bystanders assemble on Theresienwiese to support the sailor mutiny in Munich, November 1918.

In his introduction, Gerwarth explains that reinvestigating those personal letters and memoirs of notable contemporary observers such as Thomas Mann, Käthe Kollwitz, and Max Weber provide a window to understand the variety of political opinions that swirled during this period. It was a time of profound uncertainty for those who lived through it rather than a predestined failure, as modern historians have come to observe it.

Weimar was not a “stillborn” republic. Given the fierce opposition it faced from agents of the far-left and far-right, Gerwarth draws attention to the successful attempts by the socialist leadership to reform the old-world order and transform Germany into a modern, democratic state. In this way, Gerwarth’s book is a wonderful addition to the history of the Weimar Republic.