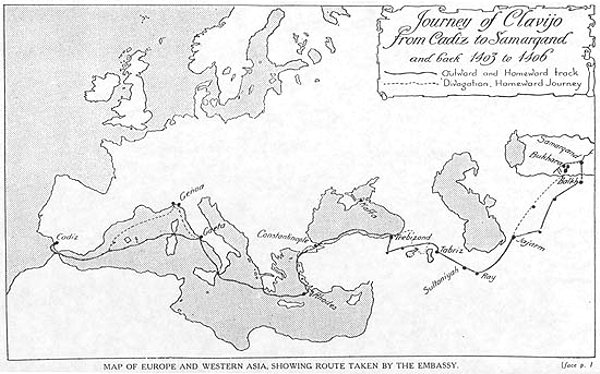

On September 8, 1404, the Castilian diplomat Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo reached the Silk Road city of Samarkand. He had travelled over five thousand miles by foot, sail, horse and camel; passed through steppe, deserts, seas and mountains.

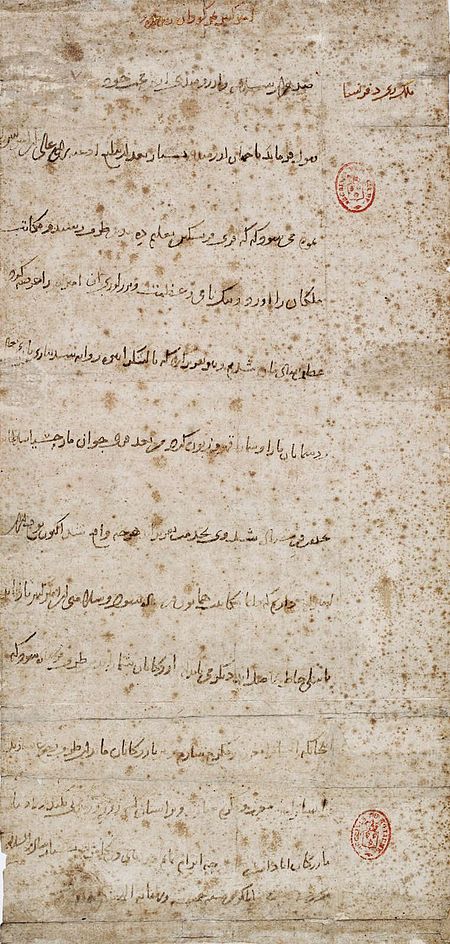

Now he had reached his destination: the capital of a vast new empire created by a military genius, mass murderer and patron of the arts named Timur (meaning “iron” in Persian). De Clavijo’s lord, King Henry III of Castile, had dispatched him to learn more about the man who Europeans called Tamurlane. If possible, he was to forge a peace treaty with the world-conqueror, whose sack of Baghdad alone caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands.

Clavijo recorded his entrance to the capital in great detail, noting the stores of “silks, satins, musk, rubies, diamonds, pearls, and rhubarb” carried from China, the painted elephants, vast tent pavilions with fluttering jeweled banners, and the frenzied pace of construction. He noted that work on the largest mosque in the city had been completed just before his arrival, but Timur ordered its gate to be torn down again because it lacked grandeur.

The arrival of Clavijo and the party of other ambassadors who he accompanied to the cosmopolitan city provoked mild interest, but mainly on account of their strange clothes and quaint customs. Medieval Castilians, it seems, were regarded as rather backward and provincial in the world of the Silk Road. Upon their entry to the city, he recorded, the party passed through a “plain covered with gardens, and houses, and markets where they sold many things.” They came to the gates of the city after several hours travel through this lush hinterland, being greeted by “ six elephants, with wooden castles on their backs”:

The [Samarkand] ambassadors went forward, and found the [Spanish] men, who had the presents well arranged on their arms, and they advanced with them in company with the two knights, who held them by the armpits, and the ambassador whom Timour Beg [Tamerlane] had sent to the king of Castille was with them; and those who saw him, laughed at him, because he was dressed in the costume and fashion of Castille.[1]

De Clavijo referred here to Hajji Muhammad al-Qazi, a Chagatai courtier who had visited the court of Castile in Toledo several years earlier. Al-Qazi had been sent by Timur to offer gifts and letters to the Iberian monarch – Clavijo was now in Samarkand to return the favor.

Why was a small Christian country on the farthest western fringe of Europe interacting with a Muslim emperor of central Asia in the first place?

The era of Timur (known to early modern Europeans as Tamerlane) marked a high-point in what has been called the ‘archaic globalization’ of the world, a period when travelers from the Christian, Muslim and Chinese worlds (like Clavijo’s rough contemporaries Ibn Battuta and the Chinese admiral Zheng He) successfully travelled vast distances across Eurasia by land and sea.

As the Oxford historian John Darwin noted in his book After Tamerlane, Timur was a figure of crucial importance in world history because he was the last great nomadic warlord.[2] Like the armies of Attila the Hun and Ghengis Khan, Timur’s forces were multi-ethnic conglomerations of Turkic, Mongol, Chagatai, Persian and north Indian peoples who were united under a common banner by the sheer charisma and military skill of a single man. His empire was not a state in the traditional sense, but a pan-tribal confederacy held together by military force. Timur’s tactics were highly sophisticated, requiring years of planning and complex organization.

Yet in fundamental ways they were pre-modern: like Genghis Khan, Timur and his commanders relied upon the mobility of massed mounted archers who could repeatedly gallop toward opponents, launch a volley of arrows and hasten away. His horseback archers, fighting at the dawn of the advent of gunpowder weaponry, were the last nomad army that could threaten the settled, urbanized states of China, south Asia, the Arab world and Europe.

By contrast, the “gunpowder empires” that succeeded Timur – the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, British and French in Europe, the Mughals (who were themselves an offshoot of Timur’s dynasty) in India, the Qing in China – all relied on conscripted armies, state finances, and ‘hi-tech’ devices like musket rifles, cannons and sailing ships. The triumph of these more modern approaches to conquest and empire in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries marked an epochal transformation. Ever since agricultural city-states emerged in Mesopotamia and Egypt in the 4th millennium BCE, human societies had been divided between hunter-gatherer or pastoralist nomads and settled cultivators. The threat of invasions by nomads from the vast steppes of Eurasia had instilled terror in town-dwellers from the earliest written records in Sumeria to the Middle Ages. After Timur, the agricultural, urban model of human society decisively won out over that of nomadism. The winners modeled ‘civilization’ in their own image.

Yet although Timur was famous for his cruelty – in one grisly episode, he supposedly murdered all 70,000 inhabitants of the Persian city of Isfahan for resisting his occupation – he was by no means a barbarian. Indeed, Clavijo was clearly overawed by the society he encountered in a region that is today regarded as a desert backwater. He was impressed by the gardens surrounding Timur’s palace, by the enormous variety of goods that the Silk Road yielded, and by the splendid feasts that Timur’s men enjoyed:

When the lord called for meat, the people dragged it to him on pieces of leather, so great was its weight; and as soon as it was within twenty paces of him, the carvers came, who cut it up, kneeling on the leather… When the roast and boiled meats were done with, they brought meats dressed in various other ways, and balls of forced meat; and after that, there came fruit, melons, grapes, and nectarines; and they gave them drink out of silver and golden jugs, particularly sugar and cream, a pleasant beverage, which they make in the summer time.[3]

Clavijo seemed particularly eager to note the favor that Timur showed to the King of Castile. When he was presented to the world-conqueror, Clavijo was surprised to find that “he was sitting on the ground.” Timur sat cross-legged before a fountain “which threw up the water very high,” wearing a silk robe and a hat studded with rubies and pearls. The Castilian proudly related that when he entered his presence, “Timour Beg turned to the knights who had seated around him… and said, ‘Behold! here are the ambassadors sent by my son the king of Spain, who is the greatest king of the Franks, and lives at the end of the world.’”

Clavijo’s mission – to forge a treaty with Timur in order to fight their common enemy, the Ottoman sultans of Turkey – ultimately failed. Nonetheless, his account gives us a fascinating glimpse into a now-vanished world (as do the entrancingly vivid memoirs of Timur’s direct descendant, emperor Jahangir of the Mughal empire). Timur was the final manifestation of a mighty world-historical force: the nomadic empire. Turkic and other central Asian warlords would continue to control the Russian steppe and the Silk Road cities for centuries, but never again would a leader from the center of what some called “the World Island” of Asia cast fear into the hearts of Chinese emperors and Christian kings alike.

Less than two hundred years later, the Christopher Marlowe – the celebrated Elizabethan playwright known for his brilliance, homosexuality and violent death in a tavern brawl – would write his most celebrated play, the full title of which gives insight into the mixture of wonder and fear that surrounded Timur’s legacy: Tamburlaine the Great, who, from a Scythian Shephearde, by his rare and wonderfull Conquests, became a most puissant and mightye Monarque. And (for his tyranny and terrour in Warre) was tearmed, the Scourge of God (London, 1590).

Already by Marlowe’s time, Timur and his Silk Road world of nomads and warriors had become the stuff of legend. The balance of power had now shifted from nomadic tribes to emerging nation-states. Charismatic warlords had been supplanted by maritime monarchs like Phillip II of Spain – the descendant of Clavijo’s Castilian king— or controllers of vast state bureaucracies like the Qing emperors of China. Yet for Marlowe, Timur’s legacy remained:

Then shall my native city, Samarqand…

Be famous through the furthest continents,

For there my palace-royal shall be placed,

Whose shining turrets shall dismay the heavens…