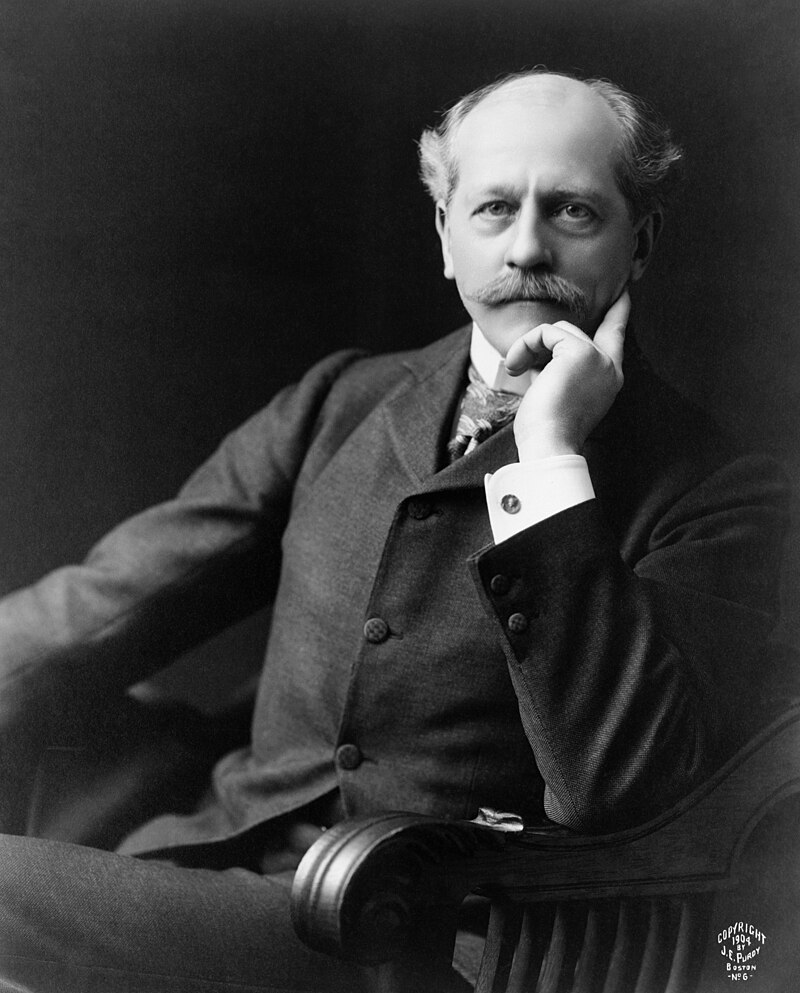

Percival Lowell was a prominent astronomer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who believed in the existence of a planet beyond Neptune. He first shared this hypothesis in December 1902, during lectures at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. These lectures were later published in 1903 as The Solar System.

Lowell’s belief in a ninth planet, which he called “Planet X,” was initially based on supposed links between meteor streams and planetary orbits. For example, he proposed that the Perseids and Lyrids were connected to an undiscovered planet about 45 astronomical units from the Sun.

Lowell argued, “This can hardly be accident... it means a planet out there as yet unseen by man.”

The Hunt for Planet X

In 1905, Lowell began his search for Planet X. For more than a decade, he worked on the project as his time allowed, employing telescopic photography and mathematical calculations.

Initially, he focused on comet and meteor predictions, but he later turned to irregularities in Neptune’s orbit. To assist with calculations, he hired a team of human computers—individuals (often women) who performed complex computations—a practice later highlighted in the movie Hidden Figures.

Lowell launched a second phase of the search in 1910, applying more precise methods and using improved telescopes. Among these was a nine-inch instrument that proved highly effective. Observers used this telescope to capture images of Pluto in 1915, but the faint images were not identified as a planet until years later.

Lowell published his definitive work, Memoir on a Trans-Neptunian Planet, in 1915, detailing his mathematical predictions for the location of Planet X. However, Lowell passed away in 1916, and with his death, the search for Planet X temporarily halted.

Reviving the Effort

The search resumed in 1927 under Roger Lowell Putnam, Lowell’s nephew and sole trustee of Lowell Observatory located in Arizona.

To continue his uncle’s work, Putnam oversaw the construction of a 13-inch astrograph, a specialized telescope for photographic observations. The funding came from Percival Lowell’s brother, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the president of Harvard University at the time.

The new telescope arrived at Lowell Observatory in February 1929. Under the guidance of observatory director V. M. Slipher, Clyde Tombaugh, a 23-year-old self-taught astronomer, was trained in using the equipment. On April 6, 1929, Tombaugh took his first photographic plate, marking the start of a fresh search.

Discovering Pluto

February 18, 1930, began as an ordinary day for Clyde Tombaugh.

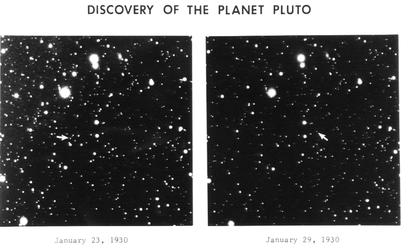

That morning, he tuned in to his favorite Mexican radio station, prepared the blink comparator—a device used to systematically compare photographic plates—and settled in for yet another painstaking day of peering through the microscope eyepiece. The plates captured images of the Delta Geminorum region of the sky, taken weeks earlier, on January 23 and 29.

By mid-afternoon, Tombaugh had meticulously analyzed about one-quarter of the plates when he spotted a faint image flickering in and out of view. Experienced enough to identify a potential planet, Tombaugh grew increasingly excited as he measured its position and cross-checked a backup set of plates captured with a smaller telescope. The mysterious object appeared exactly where he expected.

Tombaugh immediately called in colleague Carl Lampland to examine the findings. Convinced he had indeed discovered a planet, Tombaugh then walked down the hallway to the office of Slipher and announced, “Dr. Slipher, I think I found your Planet X.” Together, the three men confirmed this was no ordinary celestial body and agreed it was a planet.

Slipher instructed Tombaugh to capture additional photographs that night to verify the discovery. However, Tombaugh’s exhilaration quickly turned to frustration as the evening brought cloudy skies. Struggling to contain his anticipation, he passed the time by picking up mail in town, eating a hasty dinner, and even watching The Virginian, a film starring Gary Cooper.

Tombaugh finally succeeded in photographing the object again on an ensuing night, confirming it was, in fact, a planet. The discovery was officially announced on March 13, 1930, a date rich with significance as it marked what would have been Percival Lowell’s 75th birthday as well as the anniversary of Uranus’s discovery in 1781.

The new planet was named Pluto, after the Roman god of the underworld. Its symbol, a combination of its first two letters, P and L, were also Percival Lowell’s initials and served as another tribute to the late founder of the Observatory.

Evolution as World

Pluto’s story didn’t end with its discovery. Researchers discovered its largest moon, Charon, in 1978 and detected Pluto’s atmosphere a decade later. Most dramatically, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft offered a tantalizing view of Pluto in 2015, transforming it from a distant dot into a dynamic world with moons, geological activity, and atmospheric phenomena.

New Horizons also brought to the fore an ongoing debate about Pluto’s planetary status. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU)—the organization generally in charge of assigning official names and designations to astronomical objects—reclassified Pluto as a dwarf planet.

Reclassification is common in the field of scientific nomenclature.

As scientists learn more about a beetle or a particular type of fern or, in this case, a planetary body, they sometimes realize it fits better into another classification. Many naturalists, for instance, once classified whales as fish but eventually realized they are mammals and so reclassified them accordingly.

Thus, the idea of reclassifying Pluto was not shocking, whether one agrees with the reasons for making the change. But the way the reclassification happened raised a lot of eyebrows around the world.

The IAU famously held a vote in the waning days of its 2006 general assembly, at a time when many scientists—including most who study planets—had already left. The actual definition also caused a lot of confusion and anger, as it was convoluted and nonexclusive (one part of the definition requires a body to orbit the Sun; by this definition, the thousands of planets known to orbit stars besides our Sun are not technically planets).

Despite the reclassification, the debate over Pluto’s planetary status persists, symbolizing humanity’s drive to explore, question, and refine its understanding of the universe.

Pluto captured the imagination of scientists and the public alike after its 1930 discovery, and it continues to inspire today. Percival Lowell would be proud.

![]()

Learn More:

Pluto and Lowell Observatory: A History of Discovery at Flagstaff. Kevin Schindler & Will Grundy. 2018. The History Press. 192 pages.

Discovering Pluto: Exploration at the Edge of the Solar System.

Dale Cruikshank & William Sheehan. 2018. University of Arizona Press. 504 pages.

The Pluto System After New Horizons. Alan Stern, Jeffrey Moore, William Grundy, Leslie Young, Richard Binzel (editors). 2021. University of Arizona Press. 688 pages.

Planets X and Pluto. William Hoyt. 1980. University of Arizona Press. 302 pages.

Clyde Tombaugh: Discoverer of Planet Pluto. David Levy. 2007. Sky Publishing. 232 pages.