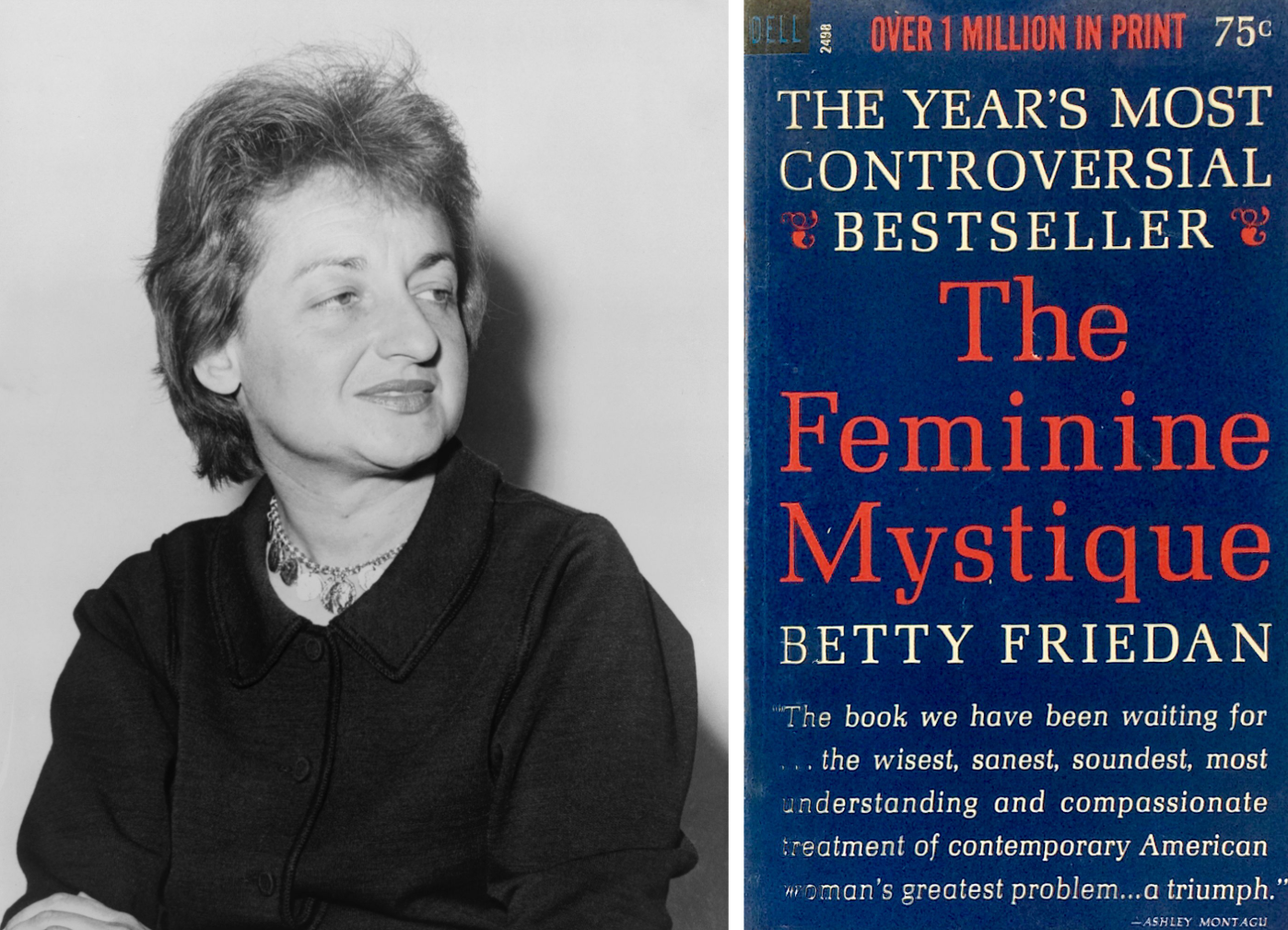

When W.W. Norton published Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in February 1963, it printed just 3,000 copies. This small figure proved grossly inadequate as sales quickly exceeded the million mark, helping to spark a mass movement that transformed women’s legal status.

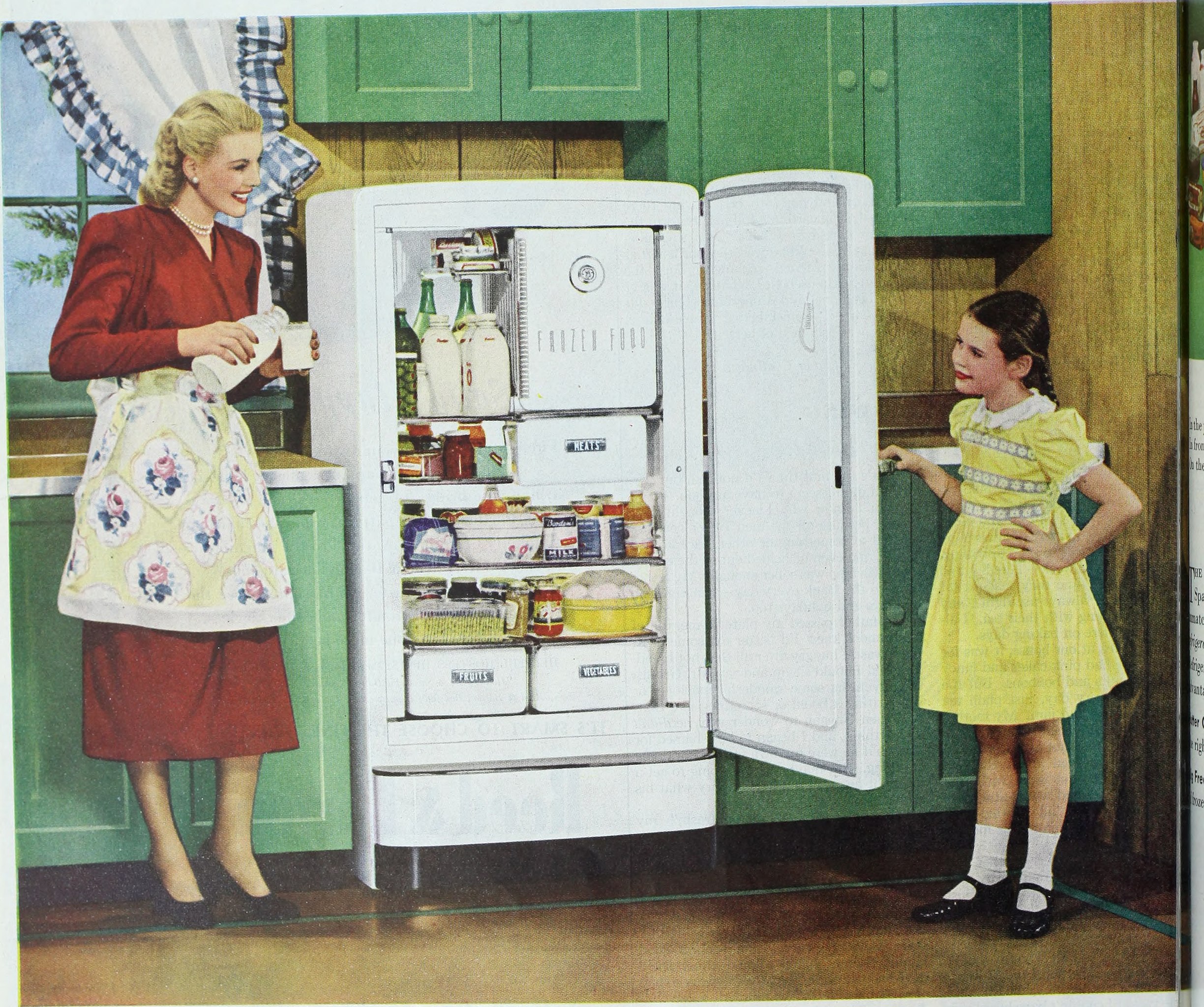

Friedan’s book encouraged women to break free of what she called “the feminine mystique,” a concept insisting that women’s true fulfillment was to be found through dedication to household labor and their roles as wives and mothers.

Although she was a white, middle-class suburban wife and mother sharing many of the characteristics of the readers whom she set out to attract, Friedan was not exactly like the frustrated women she portrayed in the book.

Raised in a middle-class Jewish family in Peoria, Illinois, Elizabeth Goldstein thrived in high school as a successful student, writer for the student newspaper, and co-founder of the school’s literary magazine. She went on to Smith College, where she studied psychology and completed a year of graduate work at the University of California-Berkeley.

In 1943, she moved to New York City and found writing jobs, first with a socialist news service that advocated for the working class, and subsequently with a left-wing union publication. In both positions, she reported on the struggles of women workers and working-class families.

In 1947, she married Carl Friedan, a theater producer and advertising executive with whom she bore three children. They shared what became a tumultuous marriage, caused in part by Carl’s discomfort with his wife’s success. The couple divorced in 1969.

Living in the New York suburbs, Friedan combined domestic obligations with freelance writing for many national publications, especially women’s magazines. Drawn to debates over the role of college education in women’s lives, Friedan analyzed survey responses of fellow Smith alumnae about their post-college experiences in 1957. She then spent the next five years analyzing the contents of women’s magazines, reading social science research, and interviewing experts in human psychology, educators, magazine editors, and hundreds of women.

The result was The Feminine Mystique.

Much of the book explained how the feminine mystique was constructed and propagated by a range of individuals and institutions. Social scientists, such as Margaret Mead and advocates of Freudian psychology, stressed sex differences, emphasizing women’s biological function as the determining factor of the role they should play in society.

Educators instilled in women the notion that they should prepare for lives dedicated to domesticity, not to careers or purposes outside the home. Manufacturers and advertisers sought profits by encouraging women to buy products to enhance their roles as housekeepers and sexual partners.

Throughout the book, Friedan emphasized the frustration and dissatisfaction that women reported about their domestic confinement, which rendered them unable to realize their full capabilities and unique identity. “The feminine mystique has succeeded in burying millions of American women alive,” she wrote, likening women’s experiences to living in “comfortable concentration camps,” an analysis that she subsequently regretted.

And this was not only bad for women. Friedan argued that the stunting of women’s growth drove them to live vicariously through their children and husbands, damaging them as well.

Friedan provided few solutions to what she called “the problem that has no name.” The final chapter insisted that women need not reject marriage and motherhood but urged them to break free of the destructive ideas that kept them from finding a purpose outside the home.

She asserted that women’s education must prepare them for a life that forged their true identities and employed their full capacities, proposing a GI Bill for women whose domestic commitments denied them the opportunity to complete their education.

Friedan acknowledged the discrimination against women in business and the professions and mentioned the need for maternity leave and childcare facilities, but she did not outline a systematic plan for social reform. Instead, she relied on the testimonies of the women she interviewed to enable readers to understand their domestic predicament and find their own ways to break out of the feminine mystique.

Given Friedan’s history as an advocate for working-class and working women in the 1940s, their omission from The Feminine Mystique is glaring. Her book focused exclusively on white, middle-class, educated women. It neglected to address the particular needs of single mothers, women of color who faced dual discrimination, women whose economic precariousness forced them to work outside the home, or those who struggled to make ends meet on their husbands’ meager wages.

Despite these limitations, the book attracted a vast readership and played a key role in drawing women into what would be called the second-wave women’s movement.

Friedan soon recognized that it was not enough to change individual women’s consciousness. Ending the feminine mystique required changing society itself.

Linking up with advocates for women in Washington, D.C., she became a celebrity, speaking all over the country and advocating for anti-discrimination laws and other structural changes to enable women to reach their full potential.

Friedan also helped establish organizations to advance gender equality. In 1966, she co-founded and served as the first president of the National Organization for Women, and she was among the founders of the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws in 1969 and The National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971.

Often uncomfortable with challenges to her prominence in second-wave feminism, Friedan crossed swords with women who represented different aspects of the women’s movement, such as labor union women, the black freedom struggle, the New Left, and particularly the emerging gay rights movement.

Friedan labeled lesbian activism the “lavender menace,” which she asserted would associate feminism with “man-haters.” She resisted endorsing gay rights until 1977 and then only did so half-heartedly.

Eclipsed by women who envisioned a more inclusive feminism, Friedan continued to research, write, and speak about women’s concerns as well as issues related to aging, publishing The Fountain of Age in 1993 as well as two memoirs. She died on her 85th birthday in 2006.

Despite Friedan’s imperfections as a feminist leader and the limitations of The Feminine Mystique, the book continues to be recognized as one of the most influential books of the twentieth century and one of the leading drivers of the movement that transformed women’s status and gender relations.