Mid-July, 64 CE, in the heart of Rome, tragedy struck as fire erupted into a massive inferno. The blaze killed innumerable people and destroyed great swathes of the city fueling debates over its details which have persisted for nearly two thousand years.

Perhaps most urgently, did Emperor Nero, regent at the time, purposely set the city ablaze or merely preside over the disaster? The firefighting techniques used by Nero’s men have also been questioned as it remains unclear if they hoped to halt the blaze or accelerate the city’s destruction.

While the trustworthiness of contemporary accounts of the fire have long been questioned and debated, the academic community generally blames poor circumstances for Rome’s destruction, believing Tacitus’s account. Public consciousness, however, is still entranced by the enthralling tale depicting a gleeful Nero celebrating as Rome burned.

First, we should imagine the fire itself in order to understand the significance of the destruction, confusion, and fear that enveloped Rome.

The fire began in the cramped shops, emblematic of Roman urban overcrowding. The rickety structures were piled around the Circus Maximus. Full of flammable wares and crops, they provided perfect kindling for the blaze. Quickly, flames raged through the heavily populated lower tenements and neighborhoods of the city.

Flames suffocated the city’s crowded streets for over a week. Masses of people surged in the canyons between winding towers of rickety tenements and even more wistful pillars of smoke and dust.

The roar of screaming people, the din of stampeding feet, and the blaze of the inferno replaced the metropolitan bustle of the Roman imperial center. The noise echoed in the narrow streets between apartment buildings, dying before it could rise from the valleys to the hilltops. Reflecting the demonic glow of the terror below, the pristine stone walls of the wealthy and awe-inspiring temples glowed burnt orange.

Tacitus, a Roman historian alive during the Great Fire, told the story of the fleeing crowds. Referencing the mythical Greek Orpheus, Tacitus wrote, “when people looked back, menacing flames sprang up before them or outflanked them.” Those who looked back, as Orpheus did to gaze at his wife Eurydice, were sent to the depths of the underworld by the flames.

Describing the maelstrom in his book The Great Fire of Rome, modern historian Joseph Walsh stated with morbid irony, “the same layout and materials that made it easy for the fire to spread made it difficult for [Rome’s] residents to escape.”

In the throng, the imperial night watchmen, the vigiles urbani, clubbed their way against the flood of fleeing plebeians; some fought the flames, others looted the abandoned buildings, and some seemed to be demolishing other buildings outside the fire’s path. Importantly, they all claimed to be under orders from the crown.

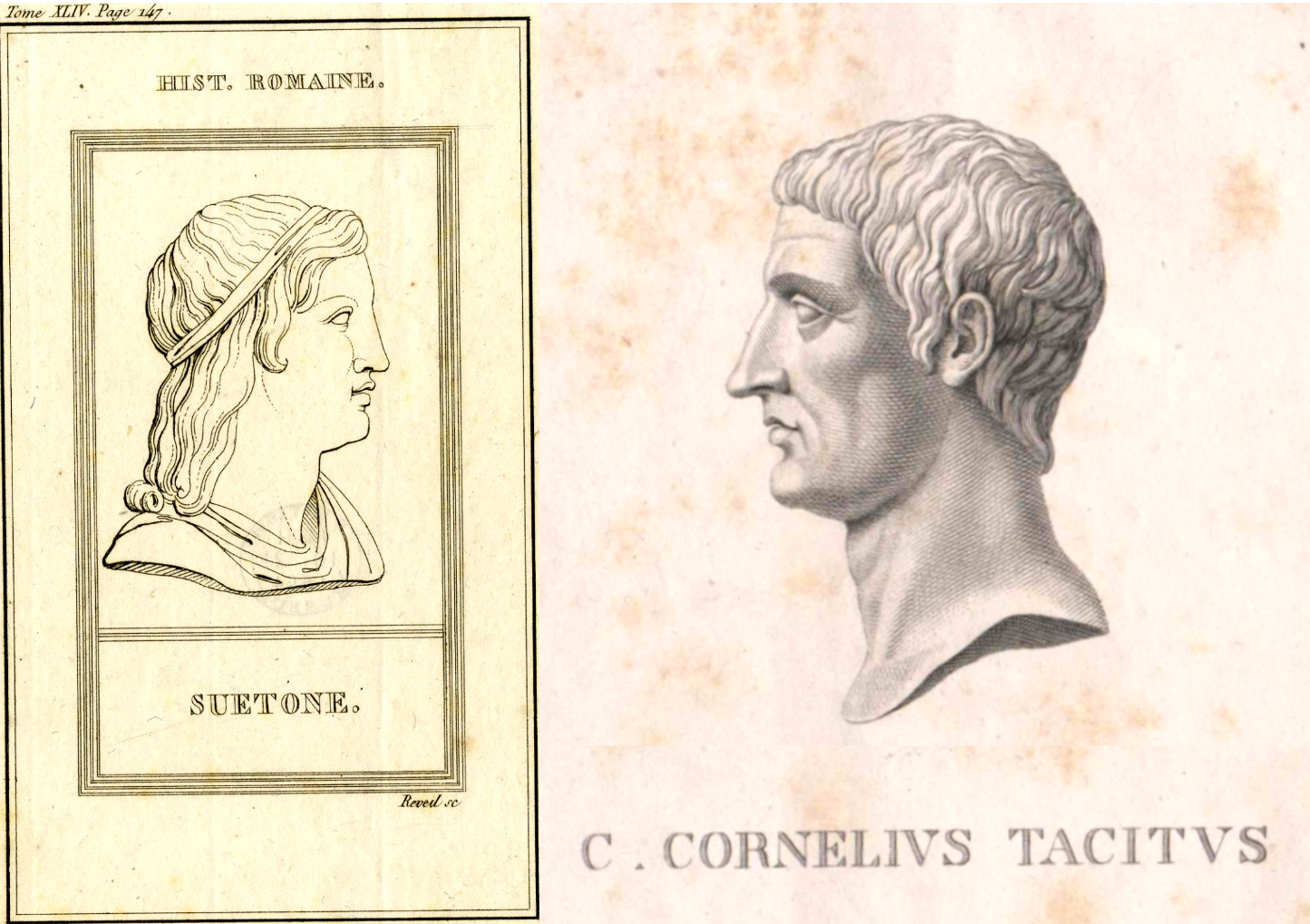

According to the Roman historian Suetonius (b. 69 CE), the vigiles’ methods seemed rather unorthodox as firefighting techniques, implying a destructive nature. Suetonius wove a tale depicting how the greedy and crooked Emperor Nero had employed his vigiles to knock down unburned stone buildings with their siege weapons and burn them even as the structures escaped the Great Fire’s wrath.

Suetonius explained the reported acts of the vigiles by claiming Nero had wanted to demolish the cramped and aging city to raise a new Rome, a gleaming city straight from his imagination.

Tacitus, ever the skeptic in comparison, posited a different conclusion. In the absence of evidence to substantiate Suetonius, he wrote that perhaps such men acting “under orders,” had lied and may not have been vigiles at all. Instead of a massive imperial conspiracy, Tacitus imagines greedy opportunists who merely “wanted to plunder unhampered” before the flames destroyed the abandoned riches left behind as people fled the flames.

Many opinions, including a large portion of popular culture, have sided with Suetonius’s account blaming the fire and all subsequent destruction on the Emperor Nero. With this conclusion, the fire stands as an indicator of Nero’s (and the Crown’s) inherent hedonism and remains a blazing symbol of certain unpopular and eccentric Roman emperors.

Suetonius despised Nero so much he included in his account rumors that the young emperor longed to rename Rome “Neropolis,” and claimed the young emperor had Oedipal desire for an intimate relationship with his own mother. The list of Suetonius’s indictments against Nero, however, does not stop there. Without any remaining evidence to support his claims, his scornful account quickly begins to seem embellished.

Modern historians have come to a consensus that Tacitus, not Suetonius, is a more reliable source about the fire’s extent and the firefighting techniques implemented. Tacitus was alive during the conflagration unlike Suetonius who was not born until four years after the blaze. Tacitus’s writing also indicates a far less personal hatred of Nero, and he takes a more impartial stance towards the known and unknown aspects of the start of the fire and the tactics of the vigiles.

Suetonius, in a far more emotional and frantic rant, clearly wanted to destroy any positive or credible aspects of Nero’s existence. Tacitus seems to let his readers draw their own judgements rather than Suetonius’s literary indictment, making Tacitus appear more trustworthy.

Modern investigators are confronted with a basic problem: no physical evidence remains of the fire. Long gone are the possibilities of forensic tests, chemical traces, or witnesses to interview. We are left pasting together mentions from Tacitus, Suetonius, and other sources that span the centuries since the blaze. Objectivity, truth, and hard facts remain unattainable with so much time having passed.

Nevertheless, debate over the Great Fire stumbles on. Interpretation of old materials with new theories and approaches still grants new insights into the ancient world and includes otherwise overlooked people, cultures, and places in the historical narrative.

Recently, the prevailing opinion of Roman historians is now that the destruction of structures with siege weapons mentioned by Tacitus and Suetonius was most likely the vigiles attempt at creating a firebreak, not an imperial real estate scheme.

By destroying a path through the city, the vigiles had hoped to suffocate the fire, limiting its consumption of the city to within the boundaries of their firebreak and saving the city beyond. This insight has provided Roman historians with new insights into interpretation of other periods surrounding the fire and the opinions of the emperors.

The Great Fire is an unquestionably important event in international history. For hundreds of years, it has signified a key moment when the Roman emperors truly became symbols of unencumbered hedonism. However, as may be the case here, even the most popular historical narratives must always be questioned and sometimes rewritten entirely.

![]()

Further Reading:

Roman History Introduction:

Potter, David S. Ancient Rome: A New History. Third Edition. New York, New York: Thames & Hudson, 2018.

On the Great Fire:

Walsh, Joseph J. The Great Fire of Rome: Life and Death in the Ancient City. Witness to Ancient History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019.

Dando-Collins, Stephen. The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City. 1. ed. Cambridge, Mass: Da Capo Press, 2010.

Ancient Authors:

Tacitus, Annals, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/tacitus/annals/15b*.html

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Suetonius/12Caesars/Nero*.html