Gwangju, a major city in southwestern South Korea, has been widely recognized as a center of civil resistance since May 1980, when a brutal military crackdown targeted citizens protesting against dictatorship. This violent suppression ultimately came to be known as May 18, or the Gwangju Uprising.

During South Korea’s democratic transition in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Gwangju was officially designated as the nation’s “sacred space of democratization” through a series of state-sponsored memorializations. This recognition included branding Gwangju as a “city of peace and human rights,” emphasizing the community’s legacy of peaceful organization and solidarity, often referred to as the “May spirit.”

Yet despite the institutionalization of May 18 as a democratic milestone, the event continues to resist any singular description. Its complexity is reflected in the many names used to describe it: “uprising,” “massacre,” and simply “5.18.”

May 18 was, undeniably, an atrocity committed by military leaders who used systematic violence—arrest, torture, forced disappearance, and extrajudicial killing—to tighten their grip on power.

In December 1979, shortly after the assassination of Park Chung Hee, who had ruled South Korea with an iron fist for nearly two decades, General Chun Doo Hwan and his allies staged a bloody coup d’état. For months, they suppressed citizens’ demands for democratic elections. Then, on May 17, 1980, Chun declared martial law nationwide, arrested prominent student leaders, shut down universities, and banned public gatherings.

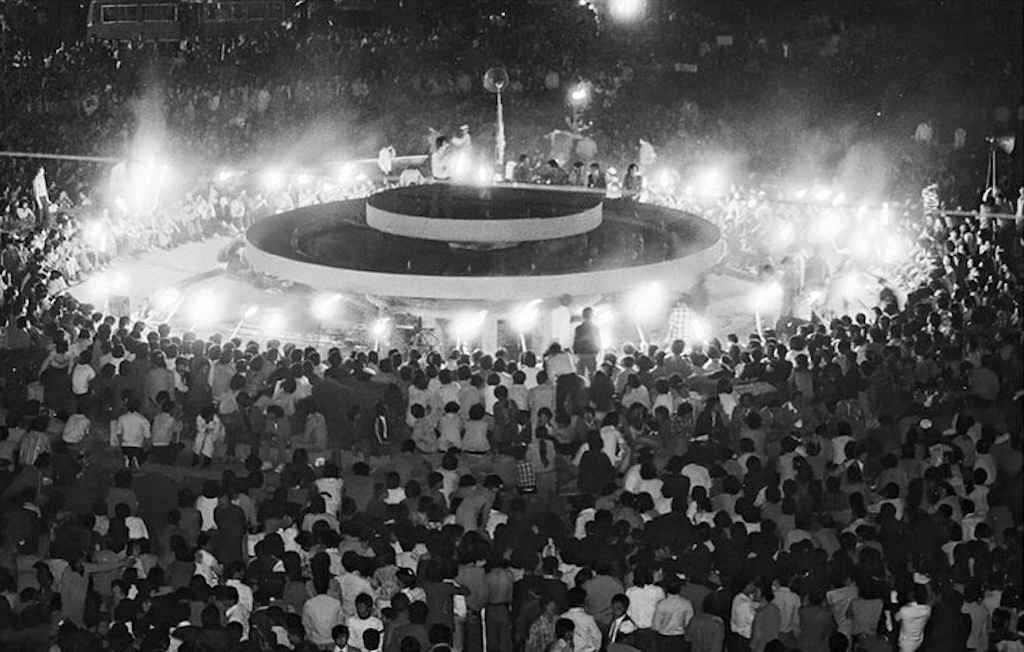

The next morning, small groups of students at Chonnam National University in Gwangju awoke to a severe military crackdown, as heavily armed forces began terrorizing their community. This onslaught marked the beginning of ten days of state-orchestrated violence, from May 18 to 27, during which hundreds were arrested, tortured, and killed.

But May 18 was also a collective, community-driven revolt against the absurdity of a military that turned its weapons on its own people. Most ordinary citizens took up arms not as political activists but to defend themselves and their neighbors from relentless brutality.

After successfully pushing troops to the outskirts of the city, Gwangju’s residents formed Citizens’ Committees and a People’s Army to govern the city, care for the wounded, bury the dead, and maintain order.

In response to the state’s control of mainstream media—which concealed the repression and branded civilians as “rioters”—the people of Gwangju published bulletins and pamphlets to tell the truth. Their voices not only condemned state terror but fostered a deep sense of solidarity during those ten days of siege.

Yet the state’s use of the term “rioter” shaped public perception then and continues to cast a long shadow over the memories of survivors today: distorting what happened, influencing official investigations in the 1980s, and fueling misinformation ever since.

Gwangju cannot be captured in a single story and is not even an event that we can say is in the past. Gwangju is not over. The perpetrators have never been fully held accountable, and South Korea’s official narrative of “post”-dictatorship democracy has obscured the enduring effects of military rule since 1987.

As the country celebrates its democratic transition, Gwangju has become a popular subject in film, television, and literature with global reach. The 2017 blockbuster A Taxi Driver, for instance, was not only released overseas but also made widely available through major streaming platforms for international audiences.

Works like these reenact “what happened” and draw a clear boundary between past and present, giving viewers the impression that the violence of Gwangju belongs to history.

Worse, far-right regimes have worked aggressively to erase and distort Gwangju’s history in the name of national unity. Right-wing media and their powerful sponsors—successors to the former military dictatorship—have manipulated established facts and even fabricated “evidence” to spread conspiracy theories that paint survivors as “North Korean spies.”

These false narratives now spread rapidly on social media, flooding public discourse with sensationalized and depoliticized images of May 18. As a result, survivors are forced to endure not only the trauma of the past but also the denial of their experiences in the present.

Gwangju is not just a traumatic event that happened in 1980—it remains deeply embedded in the present, repeatedly weaponized to ignite political polarization and obstruct justice for survivors and others whose lives have been shattered by state violence.

As authoritarianism and militarism resurge globally—and to counter the increasingly pervasive culture of denial and distortion—it is not enough to simply remember history. We must critically grasp how our present—our here and now—has been shaped by these enduring forces.

![]()

Learn More:

Human Acts by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith

Mirror Nation by Don Mee Choi

Gwangju uprising: the rebellion for democracy in South Korea. Edited by Hwang Sok-yong, Lee Jae-eui, and Jeon Yong-ho, compiled by the Gwangju Democratization Movement Commemoration Committee, translated by Slin Jung.