From its inception as a military ski patrol in 1941, the American 10th Mountain Division spent the better part of three years immersing its recruits in the art of mountain warfare before its opportunity came to fight during World War II.

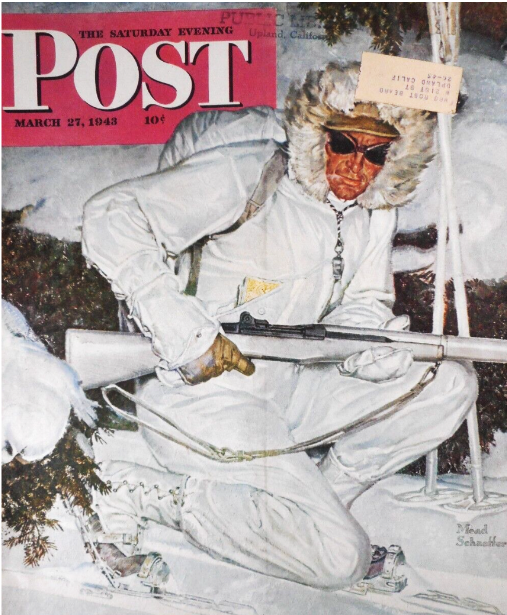

Their extreme stateside training was highly publicized. All around the country, civilians watched newsreels depicting America’s elite glacier-goggled “ski troops” rock climbing, skiing, and snowshoeing Colorado’s snow-capped peaks under heavy rucksacks and white canvas parkas.

After years of publicity, hard work, and a deployment to Alaska in response to the Japanese threat on Kiska, their orders finally came in December 1944.

Halfway across the world, Allied forces were locked in a stalemate with Axis troops north of Rome. With a commanding view of the narrow approach to the Po River Valley through the rugged Apennine Mountains, Axis forces had already frustrated multiple Allied attempts to penetrate the enemy’s 180-mile cross-country defensive line.

Called in to help break the deadlock, the 10th Mountain Division was embedded into the U.S. Fifth Army and briefed on Operation ENCORE—the final attempt to dislodge German defenders from several crucial peaks preparatory to the final spring offensive in Italy.

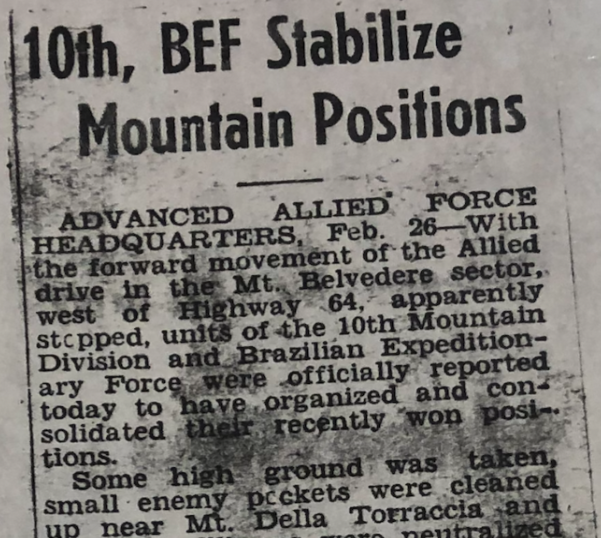

The rest of the story is well-known. From February to May 1945, the men of the 10th Mountain Division proved themselves in combat. With an audacious single-file night climb up the 2000-foot vertical escarpment of Riva Ridge and the subsequent capture of Mts. Belvedere, Gorgalesco, and Della Torraccia, the path to the Po River Valley was clear.

The 10th, heralded back home for bringing the Italian campaign nearer to its close, led the Allied assault into the Po River Valley. They would end the war at Mussolini’s Lake Garda villa, sleeping in the dictator’s bed and enjoying his rare collection of art and fine wine.

This story assumes a prominent place in our popular memory of the division at war. There is, however, another element of the unit’s history that is often forgotten: The fact that during its Italian odyssey, its soldiers fought as joint-combatants with an unlikely set of allies—South American soldiers of the Força Expedicionária Brasileira, or Brazilian Expeditionary Force (BEF).

A long-forgotten episode at the tail-end of the 10th Mountain Division’s overseas deployment illustrates the strength of ties forged between these two units in Italy.

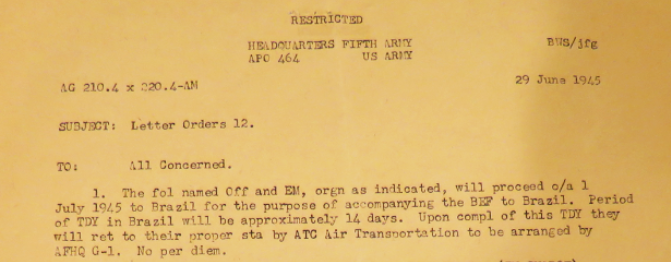

On June 29, 1945, an official directive arrived at 10th Mountain Division headquarters ordering 48 individuals across the Atlantic to participate as an honor guard for homebound Brazilian soldiers. One participant recalled how each American called to the two-week detail happened to be over six feet tall, good-looking, and heavily decorated for their service in Italy. It was, after all, important to make the right impression.

Three days later this “special platoon” boarded the USS General Meigs and set sail for Rio de Janeiro. Spirits were high. A cohort of rowdy Brazilian veterans regaled passengers aboard the ship with the sounds of Samba as they crossed the equator.

Unsure what to expect when they arrived, the Americans were stunned by their reception in Rio. Tens of thousands of people lined the wharves of Guanabara Bay to welcome home the Brazilians and their American guests. After disembarking, the honor guard was whisked away to their plush quarters on Copacabana Beach to await the following day’s homecoming parade.

The next morning this polished group of American soldiers spearheaded the Brazilian ticker-tape victory parade. While millions of civilian onlookers mobbed the returning Brazilians, American servicemen were instructed to avoid the masses, perhaps to avoid, as one American veteran postulated, the possibility of being carried off by “a lot of excited females.”

An American photographer at the event seemed to confirm the validity of this warning, observing how eventually the boisterous Brazilian crowd “became so excited they virtually broke up the parade, forcing soldiers to fight their way single file.”

Over the ensuing days, the Brazilians feted their guests with lavish meals, stood guard at the U.S. embassy, and held ceremonies to thank and decorate U.S. Fifth Army commander General Mark W. Clark and his American IV Corps subordinate, General Willis D. Crittenberger. Doling out awards and toasts of gratitude to their Brazilian counterparts, the Americans were honored alongside men of the U.S. Military Mission to Brazil in a luxurious function held at Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas’ Catete Palace.

During brief interludes, American soldiers found time for rest and relaxation. Recalling the trip at a reunion 50 years later, one veteran remarked, “We lived like kings in Rio.” They attended soccer matches, spent hours exploring Copacabana beach, climbed to the top of Sugarloaf Mountain, played tennis, and finished their trip traveling to northern Brazil via São Paulo, the Bahia, and Pernambuco before loading back onto the USS General Meigs and sailing home.

The remarkable degree of Brazilian-American unity forged during the Italian campaign of World War II is almost entirely forgotten today. Popular histories of the 10th Mountain Division regularly fail to acknowledge the battlefield cohesion achieved between these two allies during their six-month stint together as part of the U.S. IV Corps.

Indeed, American mountain troopers conducted most of their fighting in Italy in tandem with tens of thousands of Brazilians, who not only shared a common front, strategic objectives, and operational assignments, but also communication lines and supply depots, replacement instructors and liaison officers.

Wilbur Vaughn, a 10th Mountain Division veteran who participated in the trip to Rio, recalled after the war how in Italy his regimental headquarters “worked very closely with Brazilians,” and that, for long stretches, his battalion “had Brazilians immediately to the right, with their CP often working in liaison.”

Frank McCann, a leading historian of twentieth century Brazilian–American relations, has said that the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, “drawn from the army of an independent, sovereign state that voluntarily placed its men under United States command” was “American advised, trained, equipped, uniformed, and fed,” a process that resulted in military ties “that could not have been closer and still have maintained the integrity of the force’s command structure.”

The parade in Rio and the immediate circumstances that produced it—namely the Allied victory over Germany and the disintegration of the Axis powers—seemed to validate the risk Allied commanders took bringing an untrained, untested Brazilian unit into combat.

Seeking to solidify diplomatic ties immediately after the war, American newspapers, memoirs, and official histories emphasized the honorable sacrifice and positive contribution made by the Brazilian armed forces in Italy.

In one such comment General Willis D. Crittenberger assured the commander of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, General Mascarenhas de Moraes, that his unit’s wartime deeds would “have a prominent place when the history of the Second World War is written.”

Of course, Crittenberger’s vision never came to fruition. Today, public awareness of the Brazilian-American enterprise in Italy grows smaller by the year.

American military histories, memoirs, and popular retellings exacerbate the problem by focusing primarily on American troops in battle. These histories strip the Brazilians of agency by portraying them in supporting roles with no voice for themselves—either as relief units for fatigued American troops or as a gap-plugging, flank-guarding entity that, given its first serious offensive assignment, repeatedly failed to take “unclimbable” Belvedere in Autumn 1944 a few months before the 10th arrived in Italy.

Brazilian failure is often used as a framing device to reinforce the significance of the 10th Mountain Division’s battlefield exploits—a specialized group who earned its stripes succeeding where the Brazilians and other members of Crittenberger’s ragtag IV Corps had failed.

Despite their fleeting appearances in histories of the Italian campaign, it is easy to forget that numerically, at least, the experience of the BEF was nothing to balk at. The Brazilians spent more than double the amount of time on the Italian frontlines as the 10th—239 days to the 10th’s 114. During that time, they lost 443 soldiers and officers killed in action, sustained 11,617 casualties, and were responsible for capturing 20,573 Axis soldiers, bagging four entire Axis divisions in northern Italy during a two-day stretch prior to V-E Day.

Taken together, the wartime trajectories of the 10th Mountain Division and the Brazilian Expeditionary Force were more similar than different: Both were lauded within their own countries for their heroic deeds breaking the deadlock of the Italian campaign in the northern Apennines; both are remembered today as firsts and onlys—for the 10th, it was and remains the first and only American specialized mountain unit in operation; for Brazil, the BEF was and remains the first and only group of Brazilian soldiers ever to fight on foreign soil.

Similarly, both units felt they had something to prove by fighting in Italy.

For the 10th, it was whether the unit could overcome its “Johnny-Come-Lately” image by “winning acceptance from fellow combat men…and erasing the publicity-fostered and inaccurate ‘Quiz Kid’ reputation.” For the Brazilians, fighting among the Allies became a source of national pride, international recognition, and self-respect. “We had contact with Americans, British, and South Africans,” one Brazilian veteran wrote after the war, “and we saw nothing in them that made us feel inferior.”

On paper, the Brazilian experiment should never have worked. They spoke a language not understood by their allies; they depended wholly on the Americans for outfitting and training; and their fighting aptitude was unknown and broadly assumed to be nonexistent. Brazilian pessimists prior to the creation of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force argued it would be easier for a snake to smoke than for Brazil to enter the war—a phrase roughly analogous to the common English adynaton “when pigs fly.”

Yet, enter the war they did, proudly adopting—and quite appropriately, too—a new unit patch displaying a prominent green snake proudly smoking a pipe against a bright yellow background.

Part of the reason the Brazilians achieved any semblance of success alongside the 10th Mountain Division in Italy was precisely because they managed to overcome a multitude of cultural, logistical, political, organizational, and linguistic difficulties inherent to multinational military operations before the American mountaineers ever arrived in theater—most outside their control to begin with.

Understanding these difficulties is crucial to overturning the Brazilians’ somewhat undeserved postwar reputation as ill-trained amateurs and undisciplined fighters participating in a strategically peripheral campaign.

From the beginning the Allies aimed to slowly integrate the Brazilians into the American Fifth Army. This, however, proved impossible. The Brazilians deployed to Italy at a time when the most experienced Allied fighting divisions were being diverted to participate in the invasion of southern France during the summer of 1944.

Owing to the pressing need for manpower on the frontlines, after disembarking in Naples the first Brazilian troops were immediately shipped to staging areas for training and equipping.

American officers recalled how through a misunderstanding many Brazilians arrived in the Mediterranean without tents, jackets, or bedding supplies. Hundreds of soldiers were wearing worn out shoes, some many sizes too big.

Others recalled how local Italians threw rocks at the disembarking Brazilians when they mistook their old-fashioned woolen gray uniforms for those of the German invaders. It is said they only stopped when they noticed soldiers of color integrated with white comrades—a distinctly non-German characteristic.

Upon their arrival, the Brazilians’ American-donated, force-marked equipment (weapons, ammunition, demolitions, etc.) was nowhere to be found. They were in dire need of combat training, but American liaison officers complained that “nothing could be done of a definite planning nature on this, prior to the arrival of the equipment, as no one knew exactly what was arriving.”

Through another miscommunication, there weren’t enough M-1 Garands to go around, a development that infuriated Brazilian commanders who had been promised the latest in American arms. When told they could train instead on five thousand surplus bolt-action rifles collecting dust at the supply depot, the Brazilian commanders outright refused “until a definite answer arrived from the U.S.” It took two weeks for one to arrive, during which time the troops went without arms altogether.

It went without saying, as the postwar report indeed said, that the existing “system of supply at the Depot was not satisfactory.”

Issues in supply and training were intricately bound together. So much unnecessary paperwork was done that nobody checked to see whether or not Brazilian companies were receiving their allotted equipment.

Three months after their arrival, certain companies still only had one water heater instead of three, twenty water cans instead of eighty, and as little as one-fourth their allotment of G.I. soap. Repeatedly, quartermasters responsible for distributing supplies failed to check to see whether supplies reached their final destination. The first echelon of Brazilian soldiers spent almost two weeks marching and parading without equipment.

As soon as the equipment arrived, classes in cleaning, maintenance, and familiarization finally got underway. Still, according to one report, “little assistance or advice in this could be given by the small group of U.S. personnel present because its entire time was being occupied by supply problems and assisting in the receipt and issuing of the material.”

The Brazilians had little previous exposure to American combat doctrine.

Several hundred officers underwent training in the U.S., but language issues persisted both stateside and in Mediterranean. One Brazilian officer enrolled in an artillery course in Oklahoma remembered American instructors either translating English to a “terrible Spanish” they assumed the Brazilians could understand, or to a “horrible Portugal Portuguese.” Rather than clarity, he said, “confusion reigned.”

![A group of Brazilian officers enrolled at the Command and General Staff College (CGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas pose for the camera in the autumn of 1943. Photograph, RG 218, Entry UD-96, Container 5, National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], College Park, Maryland.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Screenshot%202024-01-13%20110811.png)

Certain language instructors requested by the U.S. Fifth Army in December 1944 only arrived in April 1945. Similar delays translating U.S. Army field and technical manuals into Portuguese inevitably arose as the men responsible were American reserve officers often commanding their own rifle platoons, forced to split time between training their own men and translating.

“The specifics of the organization of a U.S. infantry rifle company only became known to the Brazilians when the relevant manuals were received in August 1944, one month before its departure for Italy,” one BEF historian has noted. Other technical manuals were not translated until January 1945, five months into their deployment. Much of what they ultimately learned about fighting the American way they learned the hard way—on the frontlines.

When the 10th and the BEF began preparing for their combined assault on Mt. Belvedere in February 1945, many of these glaring deficiencies had yet to be alleviated. While certain replacement Brazilian combat teams received three weeks of training, many servicemen in the 10th had been training for three years.

As late as February 1945, the BEF’s situation in Italy remained grim. There were still no formalized training facilities; there remained a general lack of training equipment; and the Brazilian “repo-depot” was staffed by an insufficient number of linguistically qualified instructors. “Neither time nor ammunition was available for more than familiarization firing,” one postwar report noted. Some replacements never saw 60mm mortars or Browning Automatic Rifles at all before entering combat.

There was little time for backbiting. American liaison officers conceded that “the fault here was not with the Brazilians. Yes, “the Brazilians were not doing a good job” reaching American standards, yet, as they noted, “conditions were far from favorable.” “The training of [Brazilian] infantry replacements,” they concluded, “was wholly unsatisfactory up to February 5th.”

Core deficiencies were not eliminated, in their estimation, until March 19. By then, the Belvedere assault was long over, and Allied soldiers were pushing towards the Po River Valley.

Ultimately, the first group of Brazilian replacements did not complete six weeks of basic training until April 28, 1945. The war in Italy would end five days later—an irony reinforced by Brazilian Commander Mascarenhas de Moraes when he argued after the war “that the only trained troops in the Brazilian Expeditionary Force never entered combat.”

When it comes to the Brazilian combat record in Italy—especially in the months-long trial-by-fire they endured before fighting alongside the 10th—there is clearly more than meets the eye. More than just hellacious weather, mud, a determined enemy, and treacherous terrain contributed to their unsuccessful assaults on the Gothic Line during the autumn and winter of 1944.

One Brazilian officer argued after the war that his comrades were often employed on defensive missions contrary to the offensive U.S. military doctrine they were slowly being taught. Brazilians brought in to assault Belvedere in October and November 1944 complained they had been on the line far too long and lacked adequate rest.

Conducting futile frontal assaults undermined by a general lack of reinforcements and surprise—against an enemy unthreatened by Allied air support and artillery support owing to the poor weather, no less—would have challenged even the most experienced units in Italy.

Understanding the fraught history of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force makes it easier to see that the 10th Mountain Division’s presence at the July 1945 victory parade in Rio signified more than a celebration of victory against the Axis. It served as a public symbol of international unity forged against difficult odds in the crucible of war.

As a case study in coalition warfare, the Brazilian–American fight through northern Italy deserves an ongoing, closer look.

Unlike many American divisions during the war, the effectiveness, safety, and success of the 10th Mountain Division depended largely upon the American-led IV Corps’ ability to share the burden of fighting with foreign allies, liaise with their officers, train their instructors, outfit their soldiers, translate the United States’s fighting doctrine into Portuguese, coordinate communications and strategy, and mediate cultural differences that ordinarily generate substantial friction between allies.

The unlikely pairing of samba-loving Brazilian soldiers hailing from a hot, tropical climate with America’s rugged mountain ski troops in the frozen mountains of Italy should never have succeeded. Despite the difficulties they collectively faced, Brazilian and American soldiers were nevertheless “effective in the joint operations which drove the Germans off important elevations that allowed the Allied spring offensive to move forward.”

Their wartime journey serves as an ever-present reminder that coalition partners willing to work past fundamental differences can achieve enduring battlefield success.

![]()

A special thanks to Keli Schmid, special collections librarian at the Denver Public Library’s 10th Mountain Division Resource Center, for her assistance and insight during the author’s visit.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Ernest Fischer Jr., Cassino to the Alps (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center for Military History, 1976).

Maurice Isserman, The Winter Army: The World War II Odyssey of the 10th Mountain Division, America’s Elite Alpine Warriors (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019).

Major Elber de Mello Henriques, A FEB Doze Anos Depois (Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército, 1959).

Frank D. McCann, “The Forca Expedicionaria Brasileira in the Italian Campaign, 1944–45,” Army History 26 (Spring 1993).

---------. “Brazil and World War II: The Forgotten Ally, What did you do in the War, Zé Carioca?” Estudios Interdisciplinarios de America Latina y el Caribe 6, no. 2 (1995): 35–70.

Frank D. McCann and Francisco César Alves Ferraz, “Brazilian-American Joint Operations in World War II,” in Sidnei J. Munhoz and Francisco Carlos Teixeira da Silva, Brazil-U.S. Relations in the 20th and 21st Centuries (Paraná: Eduem, 2013), 83–128.

Marshal J.B. Mascarenhas de Moraes, The Brazilian Expeditionary Force by its Commander (Washington: U.S. Government Print Office, 1966).

McKay Jenkins, The Last Ridge: The Epic Story of America’s First Mountain Soldiers and the Assault on Hitler’s Europe (New York: Random House, 2004).

Joel Silveira e Thassilo Mitke, A Luta dos Pracinhas: A Força Expedicionária Brasileira—FEB na II Guerra Mundial (Rio de Janeiro: Editora Record, 1983).

Cesar Campiani Maximiano, “Learning on the Job: Training the Brazilians for Combat in the Gothic Line,” in Andrew L. Hargreaves, Patrick J. Rose, and Matthew C. Ford, eds., Allied Fighting Effectiveness in North Africa, 1942–1945 (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 120–147.

Peter Shelton, Climb to Conquer: The Untold Story of World War II’s 10th Mountain Division Ski Troops (New York: Scribner, 2003).