No revelation here: scholars are sticklers for words. Indeed, for historians of Native America, the way words are used to frame the Native past is critical. Ned Blackhawk viewed Ute history through the framework of “violence.” Pekka Hämäläinen made an argument that the Comanche past constituted an “empire.” Benjamin Madley, Jeffrey Ostler, and others saw “genocide” in the destruction of native peoples.

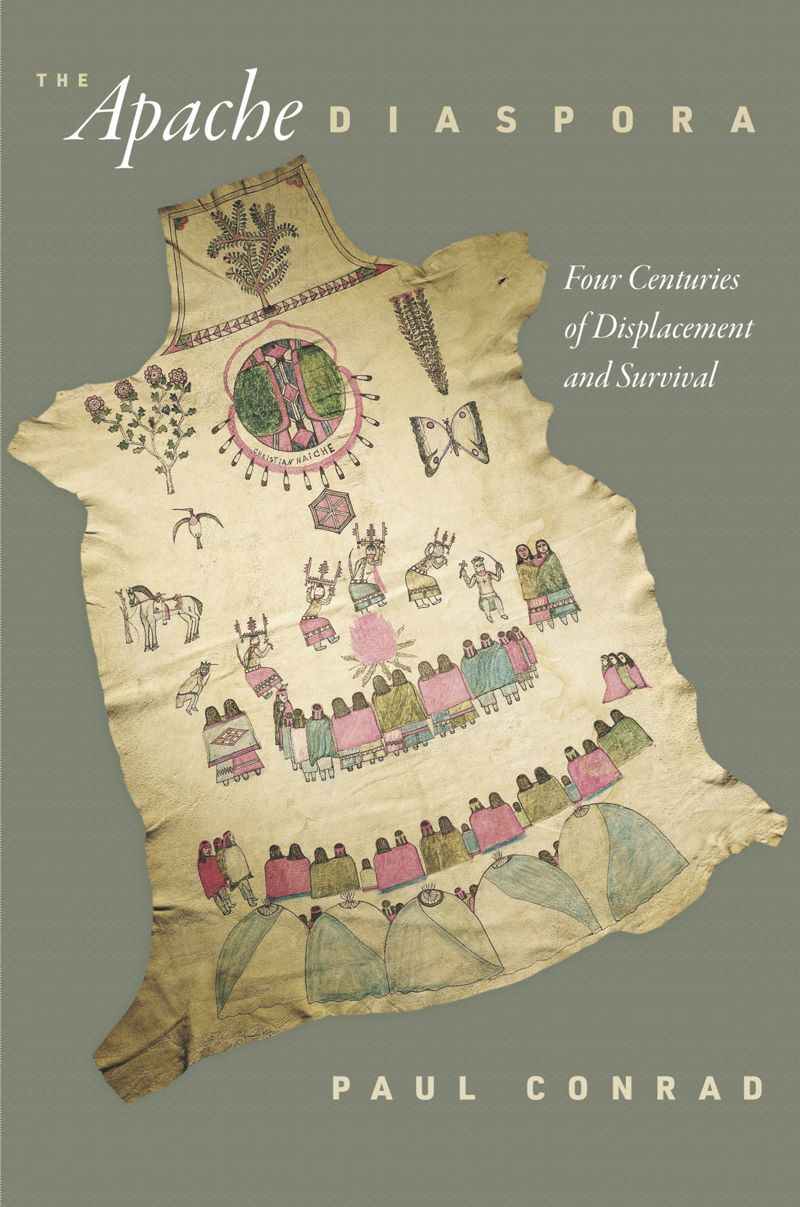

In Paul Conrad’s Apache Diaspora, the author thinks thoroughly about the words he chooses and the stories he tells with them. The two main pillars of this study – what is “Apache,” and what is “Diaspora” – prove especially challenging and important. At its core, this book explores how forced migration affected peoples now known as “Apaches,” from their ethnogenesis in the 16th century through the early 20th century.

“Peoples” (plural) is important. As Conrad notes in the introduction, popular belief views the Apaches of today as descended from an array of local families who spoke languages in the Athapaskan family. But, Conrad cautions readers, this is tricky: “It nevertheless remains the case that these designated ‘Apache’ groups have recognized themselves as distinct, with identities defined most by belonging in extended families whose ties of kinship linked together larger collectives. There was not historically (nor is there in the present day) one overarching Apache ‘tribe’ or nation.”

Despite this complexity, the author sticks to this Euro-American construct to frame his study, in part “because the term ‘Apache’ became meaningful to many Natives themselves through colonialism and diaspora,” he writes.

A Chiricahua Apache medicine man with his family inside a brush wickiup, 1880s.

Conrad then offers a glimpse into the challenges of this decision: “I also make clear the specific band names of groups wherever possible, using the Apache language terms most familiar to contemporary Apache communities and scholars, such as ‘Chihene’ or ‘Chokenen’ rather than English or Spanish referents like ‘Warm Springs’ or ‘Mimbreño.’ While some readers may be familiar with ‘Chiricahua’ as a cover term for Chihene, Chokonen, Nedni, and Bedonkohe Apaches, I follow recent scholarly usage and the preferences of some contemporary Apache groups in using the term ‘Southern Apache’ instead. This is in recognition of the fact that it was generally only Chokonens who were considered true Chiricahuas historically.”

The complexity here will baffle unfamiliar readers, frankly, and this after Conrad’s backbreaking work to sift, sort, and describe the past.

As a historian covering several hundred years of indigenous history in one book, Conrad does an admirable job stitching dispersed subjects and sources into a cohesive history. Documents from the first two hundred years prove especially challenging, though, because of their inconsistent terminology and because there aren’t that many of them.

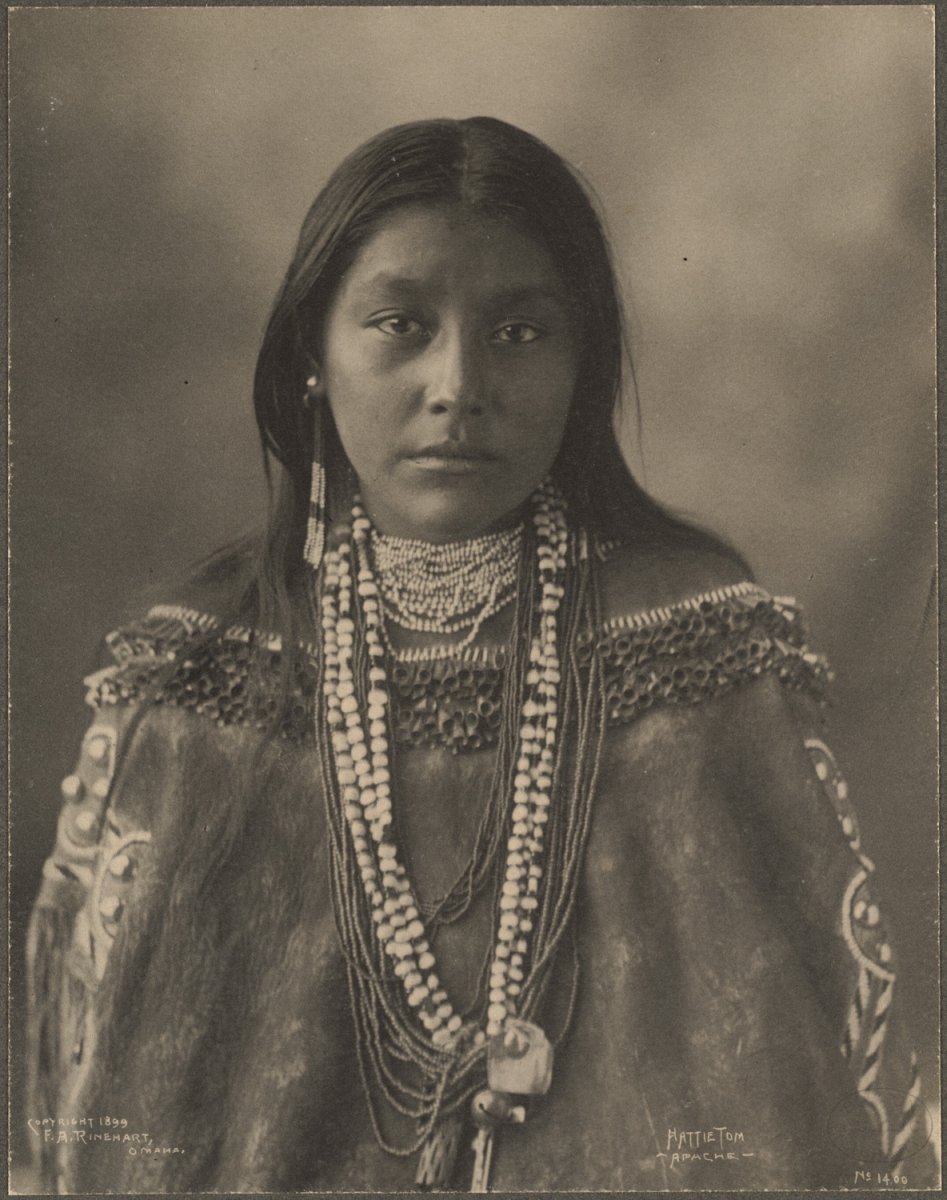

Hattie Tom, a Chiricahua Apache woman, photographed in 1899.

At times it’s difficult to tell really what’s in and what’s out of this study. For example, two paragraphs refer to “Querecho” captives, which are either “Chihene Apaches or Navajos.” Which is it, and what are the odds? Does it matter? Chapter 2 relies on baptism data relating to “‘Apaches’ or ‘Indians from New Mexico.’” Are these mutually exclusive? If so, are the differences slight or significant?

Precision may have been lost to time, but the author nevertheless asks good questions and pieces together as much meaning as possible from the fragments. In analyzing compadrazgo, or the god-parent relationship, Conrad offers: “What does it mean that so many godparents were servants and slaves? … Newly arrived Apaches probably did not choose their own godparents, but socially sanctioned ties between Apaches and other servants and slaves, including other Indians and enslaved Africans, helped shape the creation of ‘chosen’ families in Parral subsequently, forging networks of kinship and mutual support that helped individuals get by in a new, foreign setting.”

Such rhetorical gestures compensate for historical silence, though occasionally, and necessarily, they flirt with conjecture. Should these cases with unclear data have been included in this study?

In most cases, absolutely. There is no doubt that Conrad has consulted nearly all that exists.

The other framework for this study – “Diaspora” – introduces a new way of interpreting Apache history. Borrowing the term from a generation of scholarship typically based in African diasporic studies, Conrad’s use of the term highlights the long history of displacement – and the resilience of community – among indigenous peoples.

Many examples throughout the book show the power of this analysis: relocation to southern Mexico, the creation of reservations, the shipping of captives to Cuba (“An Apache Middle Passage”), and the forced removal to boarding schools, for example. While the numbers cannot compare with the African Middle Passage (nor the African diaspora in the New World), the term effectively casts indigenous and African removals, in a similar light.

Additionally, though the author does not delve into it much, his use of diaspora can dislodge quite effectively the problems of the term “indigenous,” the idea of a single people fixed in a particular place since time immemorial. The dispossession and movement of Apaches can reinforce, in fact, the determination of a people, and their strong ties to home lands in today’s Southwest and Mexico, in Canada as well as Cuba.

In the end, the complexity of terms fades when the narrative emerges beyond the middle nineteenth century. Conrad’s storytelling masterfully supports his analytical goals. Chapters on the shipping of captives to Cuba, of the capture of Geronimo, and of the troubling history of the Apache presence at Fort Marion are genuinely moving. The diaspora model pays dividends. It would be well situated in a course on Western or indigenous histories and the effects of settler colonialism.