Americans have always been haunted by the idea that the country is in decline. Underneath the buoyant optimism we have often projected runs a current of disappointment sometimes bordering on despair.

From the Puritan ministers who thundered in their jeremiads that Americans had fallen from some state of grace to Ronald Reagan who promised in 1980 to “make America great again” (yes, Donald Trump plagiarized that too) Americans have long been persuaded by the idea that the present seems pretty terrible in comparison with the past, even if that past is mythic or not quite defined.

Many Americans, I suspect, especially those of a Reaganite-Trumpian bent, see the founding of the nation as that moment of political – even moral – perfection. An unparalleled assembly of wise and public-spirited men gathered in Philadelphia and gifted us the Constitution.

We betrayed that Eden, of course, and if we could only return to that moment and those ideals we might fix all that is wrong. And if that’s a version of your jeremiad, Dennis Rasmussen’s book Fears of a Setting Sun is the book for you.

The sub-title – The Disillusionment of America’s Founders – gives away the argument. Far from being pleased with themselves for the political framework they created on their way to Mount Olympus, a remarkable number of those founders wound up deeply disappointed with the great American political experiment.

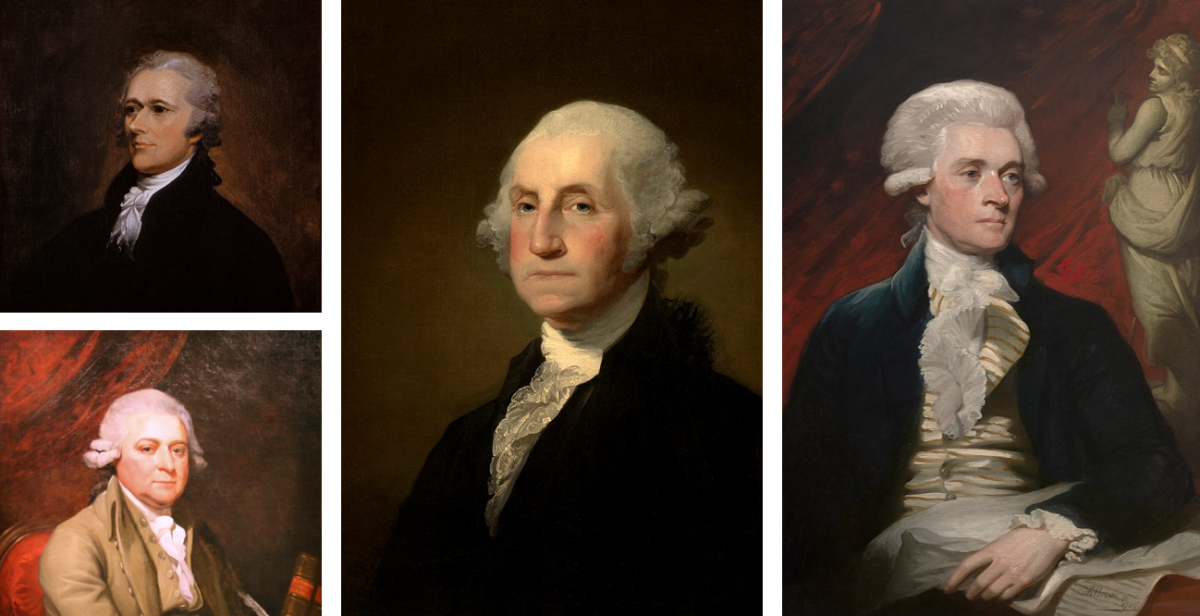

Alexander Hamilton (top left), John Adams (bottom left), George Washington (middle), and Thomas Jefferson (right).

Rasmussen organizes his book around four biographical sketches: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. They weren’t all disappointed by the same thing, and Rasmussen pairs each founder with a particular complaint. For Washington, it was partisanship. Even as he invented the office of the presidency he fretted repeatedly that the new government would be torn apart by warring factions despite his best efforts to create a balance between Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans.

Pressured into serving a second term, Rasmussen writes, he embarked on it “with a sense of grim resignation.” In fact, the partisanship of the 1790s, among the nastiest and vitriolic in our history, got so bad that Washington himself found himself on the receiving end of it. Retiring to Mount Vernon made Washington’s view of American politics no better. As Rasumussen describes it, Washington’s “vision of nonpartisan harmony was already an exceedingly distant one when he stepped down from the presidency,” and by his last year (1799), “not a happy one,” Rasumussen writes, “it had been exposed as a mirage."

Before he was a Broadway star, Alexander Hamilton was among the primary architects of the Constitution and, as Washington’s Treasury Secretary, the primary architect of the nation’s financial system. His disillusionment came just as soon as his bitter rival Thomas Jefferson became president. An unapologetic proponent of a muscular Federal government, Hamilton saw this as the only way to create a nation strong enough to preserve its liberties.

A 1902 depiction of the Burr-Hamilton Duel by J. Mund.

As the small-d democrat Thomas Jefferson began to undo much of Hamilton’s work, Hamilton fell into “despair” over the fate of the nation. Hamilton had a distrust of popular democracy – as he put it to Charles Pinckney, “Mankind are forever destined to be the dupes of bold & cunning imposture.” And writing to Rufus King, Hamilton lamented “Truly, My dear Sir, the prospects of our Country are not brilliant.” Hamilton was killed in a duel in 1804. Had he lived longer he might have only grown gloomier.

It probably comes as less of a surprise that John Adams disapproved. He has come down to us as the disapproving type. Rasmussen has chosen to focus specifically on Adams’ concern about the citizenry’s virtue – or the lack thereof. Adams was convinced, as plenty at the time were, that any republican government could only survive if citizens put the common good above their own self-interest.

As he surveyed his fellow citizens he did not like much of what he saw. Rasmussen writes, “Even in the midst of the Revolution, Adams harbored some rather serious misgivings about the virtue of his fellow citizens.” There was insult here too. In a nice observation, Rasmussen notes that “Adam’s model republican citizen was less a Spartan warrior than himself.” Adams devoted a remarkable amount of his long life to public service, selflessly pursued. No one, Adams believed, gave him his due.

If disillusionment came in the heat of the founding for Washington, Hamilton, and Adams, Thomas Jefferson’s came later. In the last decade of his life, however, Jefferson’s faith in America’s future soured, and slavery played a central role in this change of attitude.

After the Missouri Compromise Jefferson foresaw a nation torn apart by slavery. That slavery vexed Jefferson isn’t altogether surprising since slavery had contorted Jefferson’s thinking for decades. But as Rasmussen charts it, Jefferson didn’t simply see slavery as a source of increasing national division, but as he grew old he defended the need for slavery to expand westward – the source of the problem, then, were Northerners who wanted to stop that expansion. More contortions to be sure, and as Rasmussen sums it up: “He still considered himself to be an opponent of the institution, but by this point one might fairly say that with enemies like Jefferson, slavery hardly needed friends.”

There is a fifth portrait here. James Madison, who retained his optimism about America’s future to the end of his life, serves here as the rule-proving exception. While Rasmussen must have felt compelled to include Madison, I’m not sure it adds much to the thrust of this book. After all, by Rasmussen’s tally fourteen major founding figures wound up disillusioned.

Fears of a Setting Sun is an engaging, indeed fun, read, nicely written and deftly argued. More than that, it is a useful reminder at this political moment that while things ain’t what they used to be, they never were in the first place.