The dar al-Islam, or realm of Islam, is very much in the news today: strife between Taliban and authorities in Afghanistan; the horrors of the Saudi assassination of Jamal Khashoggi; the US government’s targeted immigration ban. Timely then that veteran religious studies scholar Brian A. Catlos has published an overview of the long-ruling and highly influential Islamic kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula.

In Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain, Catlos examines the importance of Islam in the formation of European and Mediterranean culture. It is intended for a broad audience, and generally focuses on top-level events.

The book covers the period beginning with Islamic expansion after the death of Muhammad in 632 C.E. through the final expulsion of Muslims from Spain in 1609. It considers major events throughout the long period of Islamic influence in the peninsula.

Kingdoms of Faith argues that the idealized conceptions of “convivencia” (peaceful co-existence) and “Reconquest” (the re-capture of Islamic land by Christian kings) through which we view Spanish history are too facile. The reality of the Islamic kingdoms in Iberia was far more complex.

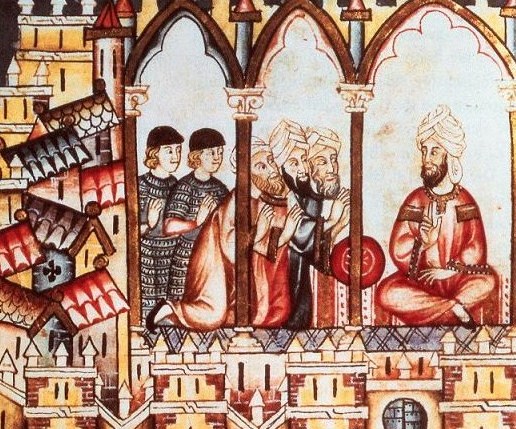

Castilian ambassadors attempt to ally themselves with Abu Hafs Umar al-Murtada.

For instance, many Muslim rulers of these kingdoms were themselves descendants of Christian Visigothic kings and queens, owing to intermarriage with the native population. One Christian ruler even dyed his beard black to conform to Arab beauty standards.

Race, ethnicity, and class divided groups to the same extent or even more so than religion did. Jews and Christians remained living under Islamic rule, protected in their faith by the dhimma, which allowed them to live unconverted under their own religious laws.

While this created a dynamic, prosperous culture in the 8th and 9th centuries, as Muslim power in the peninsula reached its zenith, seeds of unrest were already apparent. Factions emerged among competing groups—including among the ruling Umayyad dynastic heads, Muslim Arabs, Berbers, slaves from all over the dar al-Islam, Jews, and the native population which, in Iberia, had been organized into Christian Visigothic kingdoms.

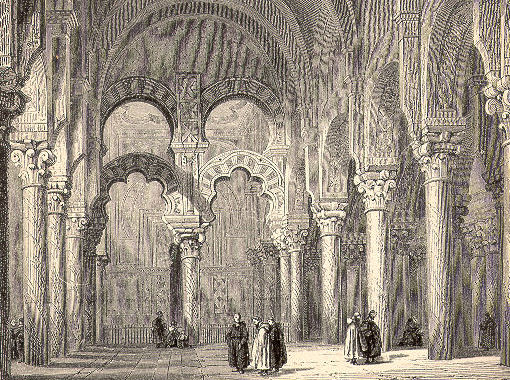

The Mosque of Cordoba, constructed during the reign of the Amir Abd al-Rahman I in the 8th century.

These groups constantly mixed and jockeyed among themselves for power. Any time there was an opportunity for a power grab, many opposed Umayyad domination. Thus, the caliphate, though rich and powerful, was toppled in just one century.

Cracks in Umayyad rule also threatened the nascent Christian kingdoms to the north, as uncontrolled Muslim aggressors seized the opportunity to take captives there. In turn, this provided a rationale for Christians to take advantage of the great material wealth of their squabbling southern neighbors.

Iberian disarray led to the emergence of independent rulers. They carved out what were known as taifas, or small kingdoms. Often, taifas were ruled by those groups who had previously found their power suppressed by the caliphs.

Thus, power was dispersed, just as Christian kingdoms were gaining the upper hand over the Umayyads. By the 11th and 12th centuries, Christian warriors headed up Islamic armies and their kings took northern Islamic cities (already divided by factionalism). Their faith became increasingly zealous, encouraged by the pope and the influx of Crusaders from around the Christian world.

But Christians incorporated into their daily lives much of the culture and science of the Muslims and Jews. The Islamic rulers, in opposition, brought in their own new factions from northern Africa, some less open to dhimma protections than previous rulers had been.

Kingdoms of Faith contends that while religious fervor nominally motivated Christians and Muslims to wage war on each other, a desire for power and control subordinated all other factors. Even after Christians began to take Muslim cities, they did not abandon the luxuries and cultural standing which Islamic Iberian culture had brought to them. In fact, even as Christians united their kingdoms, the constant threat of factionalism motivated them to set Muslims apart.

Distrust of Muslims culminated as Christians came to discriminate even against converts. The threat of division, greater than the threat of religion, is what finally saw the forced exile of Moriscos (hispanized Muslims) in the 17th century, over 100 years after the last Islamic state was brought down by Catholics Ferdinand and Isabella.

At times, the sheer volume of information presented in this work is unwieldy, and the top-down approach sometimes feels like a litany of names, battles, and dynasties. However, that does not diminish the usefulness of the book. Catlos makes his point clearly: the history of Islamic Iberia is messy and complicated.

Kingdoms of Faith should appeal both as an academic resource and as an historical narrative for the general public. Contestations about the nature of religion, culture, and the mixing of populations did not dissipate after the 17th century, nor did they remain in Spain. They remain much discussed today, just like they were at the height of the reign of Abd al-Rahman.