Loving, directed by Jeff Nichols, 2016.

I’ve just finished teaching a delightful course with my colleague, Bill Freivogel, a lawyer who covered the Supreme Court for many years as a journalist for The St. Louis-Post Dispatch. Our course, entitled “Which Supremes?” applies Supreme Court cases to film and television representations. We could not have asked for a better crescendo than Jeff Nichols’ new film, Loving (2016), a bio-pic about Richard and Mildred Loving, who were unceremoniously ripped out of their bed by a demonic sheriff one night in June 1958.

The Lovings were charged and convicted of evading Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act, a 1924 Jim Crow law that criminalized miscegenation, the intermarriage of whites and people of other races. Such laws dominated the entire Southern bloc of sixteen states, from North Carolina to Texas, from West Virginia to Florida.

The statutes were protected by a diabolical 19th Century Supreme Court, who in Pace v. Alabama (1883) defended as constitutional laws barring sexual relationships between people of different races, despite the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause staring the nine blind white men in the face.

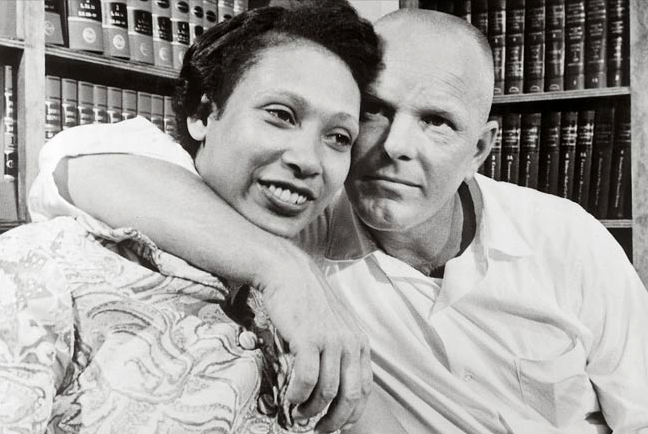

In 1967, the case of Richard Loving, a white man, and his wife, Mildred Loving, an African-American and Native American woman, reached the Supreme Court, where Chief Justice Earl Warren declared in a unanimous opinion that marriage is one of the “basic civil rights of man.”

Richard and Mildred Loving in June, 1967.

In the course, I demand that students look beyond the obvious linkages between filmic and legal discourse. In the case of Loving v. Virginia, the most pertinent film is Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1968), which features a stirring defense of the engagement of the daughter of a white patriarch played by Spencer Tracy to an African-American man played by Sidney Poitier. The final speech was filmed in May 1967 amid the Warren Court’s deliberations over the Loving case. The Court’s decision was delivered on June 12, 1967, a day that continues to be celebrated as “Loving Day,” a more needed holiday I cannot imagine in Trump’s America.

However, my approach is to see the Loving case as merely one expression of the much larger racialization of space in American social life. To connect the surveillance of the police state authorized by the anti-miscegenation laws (and thus allowing a sheriff to break into a couple’s house and stand over their bed in the middle of the night) to the cinema, I turn to the famous “Gus Chase” sequence of The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1914), a film shown proudly in President Woodrow Wilson’s White House in the middle of the tragedy of Jim Crow.

Gus, an African-American man (played by Walter Long, a white actor in blackface), chases after Flora, the “Pet Sister” (Mae Marsh). Her brother, Confederate Colonel Ben Cameron (Henry Walthall) rushes to her rescue, but before he can save the day, Flora jumps off a cliff to her death rather than allow Gus to assault her. Griffith uses parallel editing techniques to build suspense, forcing us to calculate the distance between each of the three characters with every cut.

Flora internally polices the space, vertically jumping to her death as the horizontal distance between her body and Gus’s evaporates. In legal terms, the anti-miscegenation laws equally policed the space, determining who could lie in bed with whom, and whom to lynch for collapsing the sexual space between white and black folks.

Stills from the "Gus chase scene" in Birth of a Nation (1914).

Jeff Nichols, with his recent masterful films, Take Shelter (2011) and Midnight Special (2016), is rapidly becoming one of the most accomplished filmmakers in the United States. His bio-pic Loving is a masterpiece of deconstructing the racialization of space implicit in American film.

The first shot of the film is a close-up of the face of Mildred (Ruth Negga), seen in profile. She looks down and to the right, slowly declaring, “I’m pregnant.” Nichols cuts to another close-up in single, this time of Richard (Joel Edgerton) in three-quarter profile, looking screen left. After an equally torturous delay, he declares his happiness, laughing: “Good. That's real good.” He begins looking screen right. Nichols cuts back to Mildred, who now looks screen left. Richard is barely noticeable in the left foreground of the image: what had been isolating close-ups is now an over-the-shoulder two-shot.

A final cut to a long shot of Richard and Mildred sitting together on the porch in front of their house in Central Point, Virginia establishes the film’s transformational approach: while the social forces surrounding them will demand that they stay out of each other’s frame, the film will find ways to squash them together into the same image.

While not technically a crossing of the camera axis, the disorienting close-ups which begin the film quickly give way to a coherent space in which lovers look at each other, rather than in opposite directions.

Ruth Negga and Joel Edgerton as Mildred and Richard on the porch in Loving (2016).

Nichols is doing nothing less than overwriting the racist visual language of The Birth of a Nation. Griffith’s mastery of parallel editing reinforced Jim Crow culture by naturalizing Flora’s policing of her space, always keeping Gus out of her shot.

Nichols’ Loving demands a new use of these aesthetic practices. The movement from singles in close-up to longer distance two-shots becomes the basic grammar of his film. When Richard takes Mildred to the acre of land he’s bought on which to build her a house, they begin in singles, isolated from one another, but end the scene in two-shot, as Richard proposes marriage to Mildred.

The first scene in which they begin together in the same shot occurs at their marriage ceremony: Nichols’ camera tracks to the right around a pillar in a Washington, DC city hall as they take their marriage vows before a justice of the peace. The camera remains in long shot behind the couple, all delivered to the viewer in one take. While not yet arrived in Virginia, the culture has developed new spatial rules in the nation’s capital.

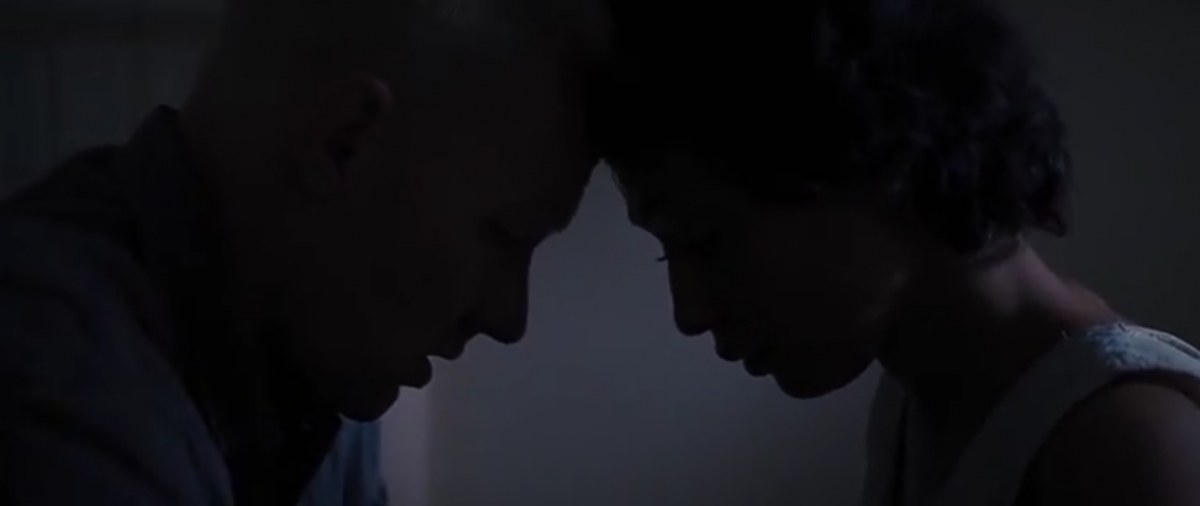

During the arrest and conviction of Mildred and Richard, and in the aftermath, they are bombarded by bizarre racial claims. The arresting sheriff denies Richard the ability to bail his wife out of jail, stating: “It’s all God’s law. He made a sparrow a sparrow and a robin a robin. They’re different for a reason.” In response, Nichols shoots Mildred and Richard finding a new visual language. As Richard tells Mildred he’s hired the best lawyer in Virginia, they lean their heads together in profile, forming a cup in the negative space between their profiles. It is one of the most beautiful images in contemporary American cinema, understated yet moving in its elegance.

Depiction of the arrest of Richard and Mildred in Loving (2016).

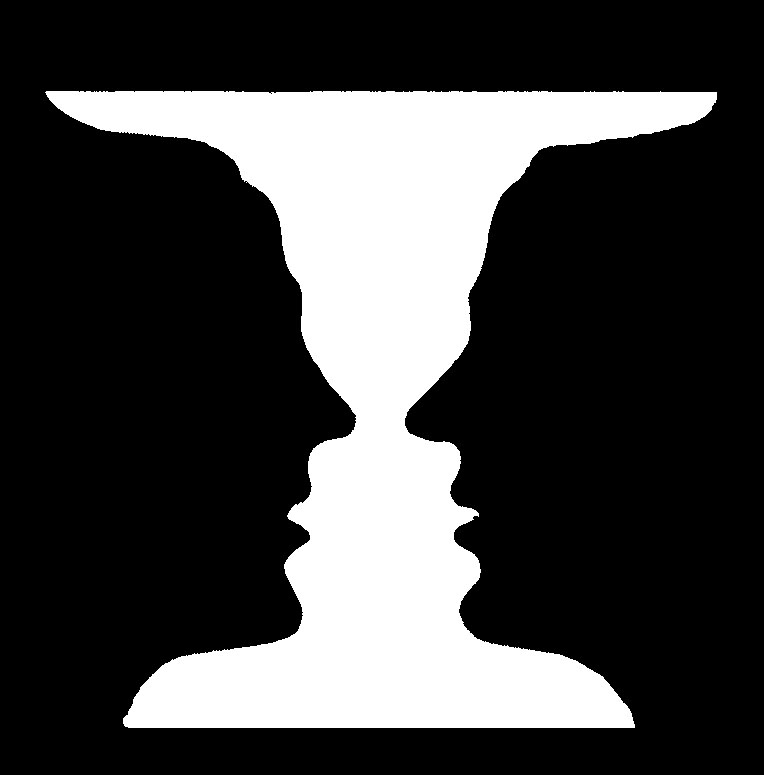

Shortly after their arrest, Richard, screen-left, and Mildred, screen-right, bow their heads together in silhouette. Their foreheads form a dark unified space atop the image, but in the slightly lighter negative space beneath them, another image forms. This replicates the famous “Rubin Goblet,” a Gestalt psychology example where if one focuses on the black exterior of the image, one seeks the profiles of two faces looking at each other, but if one shifts focus onto the white interior space, a chalice suddenly appears.

The Gestalt shift in Loving allegorizes the Loving v. Virginia decision, a sea change in American social life that transformed Jim Crow culture into an America where one could marry one’s interracial lover no matter in which of the fifty states one resided.

Even more tellingly, unlike the upright goblet in the Rubin example, the Lovings’ goblet—let’s call it their loving cup—is inverted; at this stage of the movie, their love runneth out because they have no social support to keep it legally in place. Furthermore, because of the low-key lighting of the scene, race as a visible signifier disappears: both Mildred’s and Richard’s skin seems black in reference to the light barely registering in the image beneath their connected faces.

The “Loving Cup.”

The “Rubin Goblet.”

As in the loving cup, Richard and Mildred become spatially unified, even against people helping them. The most interesting of the film’s representations is of their lawyers.

Bernie Cohen (Nick Kroll) most vigorously pursues their case after Mildred writes a letter to Bobby Kennedy, who passes the case on to the American Civil Liberties Union. A founding member of the ACLU in Virginia, Cohen immediately wants to take the case to the Supreme Court. Richard doesn’t understand what all the fuss is about, telling the lawyer to just go talk to the racist county judge, stating simply, “We won’t bother anybody.” When Cohen suggests they arrange to get arrested again, because the original arrest was five years ago, Richard and Mildred are horrified.

In all their meetings with lawyers, Richard and Mildred sit on one side of a table, with the lawyers on the other, maintaining a spatial distance every bit as significant as the racial one undergirding the legal issues. Even as late as the third act of the film, when it is clear the Lovings are going to win their case before the Supreme Court, Nichols insists upon the bifurcated representation of the legal space.

Bernie Cohen and Phil Hirschkop, the Lovings’ lawyers in the 2011 documentary The Loving Story.

Cohen comes to the Lovings to invite them to be present at the oral arguments before the nine justices. When the lawyers explain that the State of Virginia will use their kids against them, arguing that their mixed race defines them as bastards, Richard refuses to travel to the Supreme Court. After he storms out of the room, Cohen tries to convince Mildred to attend one of the most significant events of American history, but she states simply, “I won’t go without him.” Outside of their house, Cohen asks Richard what he’d like him to say to the justices in his stead: “Tell the judge I love my wife,” he declares in extreme understatement.

Nichols films the climactic Supreme Court case in a revolutionary way, in response to the refusal of the Lovings to attend. As if it were a Griffith chase sequence, he cross-cuts between the lawyers at the Supreme Court—Cohen argues they are fighting “the most odious of the segregation and slavery laws”—while Mildred and Richard are home having dinner, and then putting their kids to bed.

In response to Cohen winning one of the most important legal victories in American history, the Lovings simply walk down stairs, turn out the light in their living room, and go to bed, closing the door to the bedroom, which we see in long-shot. Nichols deconstructs the racist Griffith’s film language to the point that the very notion of motion and action in the cinema is rendered moot.

Indeed, if Griffith’s cinema is melodramatically overstated, Nichols is the master of understatement. We only learn of the victory secondhand. Mildred answers the telephone, and we hear over the line jubilant celebrations which drown out Cohen’s voice. Mildred glances out the window at her family playing in the grass, and mutters, “That’s wonderful news. Yes, I understand.”

The only character in the film who understands the importance of understatement to the Lovings is a photographer for Life Magazine, Grey Villet, sent to the Lovings’ house by their lawyers to build publicity for their case. The casting of Michael Shannon as Villet is the film’s crowning achievement.

Michael Shannon as Grey Villet takes the iconic photo of Mildred and Richard on the couch in Loving (2016).

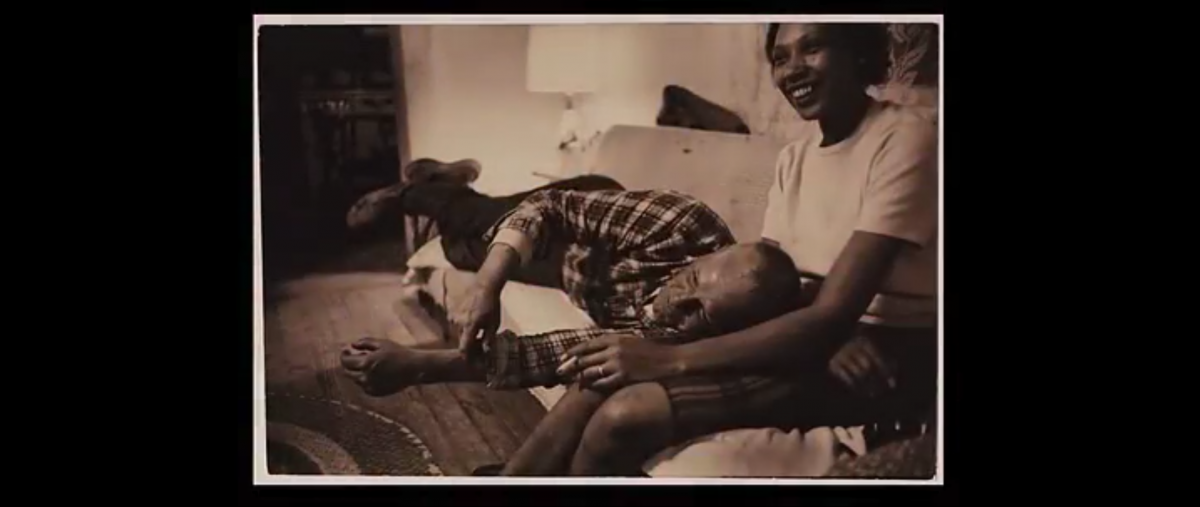

Villet spends the day with the Lovings, quietly studying them without taking many photographs. When Mildred does the dishes, explaining, “We may lose the small battles, but win the big war,” he takes a shot of her in profile, recalling the film’s opening shot. However, his patience pays off. Later that night, Richard lies his head upon Mildred’s lap while they’re watching an episode of The Andy Griffith Show on TV. Without moving his body, standing at the door jamb of the living room, the place from which the camera will film the Lovings going to bed after they have won the Supreme Court decision, Villet snaps from the hip a photograph of the lovers on the couch laughing at the TV.

The Andy Griffith Show in Loving (2016).

Scene of Mildred and Richard on the couch laughing at the TV.

As Nichols’ film ends, the credits reveal the actual photograph of the Lovings on the couch laughing, now having become an iconic image of the happiness we share if only we are sheltered from the forces of irrational discrimination. Jeff Nichols’ film, Loving joins that photograph as one of the great triumphs of civil resistance to oppression; may his artistry finally put to rest the racist cinematic grammar of Jim Crow and D.W. Griffith.

Grey Villet’s photo of the Lovings on the couch during the end credits of Loving (2016).