Few places wrestle more with their own history than Berlin—a modern capital city steeped in debates about how to remember the past. More than a simple residence for millions of Germans, it also contains a tumultuous historic narrative that is fused to the city itself.

Found at Berlin's East Side Gallery.

Berlin dates back to the 12th century. All around the bustling city, churches that would be more at home in the Middle Ages coexist with contemporary architecture. Museums dedicated to celebrating art, science, history, and the natural world dot the landscape and stand beside opera houses and statues commemorating prominent figures of German cultural heritage.

A shot of Berlin’s New Synagogue as it presently stands on Oranienburger Straße. It was heavily damaged before and during the Second World War, as a result of anti-Semitic rioting and Allied bombing.

Berliners are, if nothing else, aware of the admirable and deplorable in their past, and do not shy away from engaging with it on a critical level. The complicated and controversial history of the 20th century permeates the landscape of the German capital.

A message of peace found at Berlin's East Side Gallery.

Small brass plaques that provide minor details about victims of National Socialism are scattered around Berlin and are joined by monuments to the victims of the world wars, the Holocaust, and the famous partition of the city—all grim reminders that remembering the past is not always about celebrating it.

A couple of examples of small brass plaques found throughout Berlin that depict the former homes of Holocaust victims.

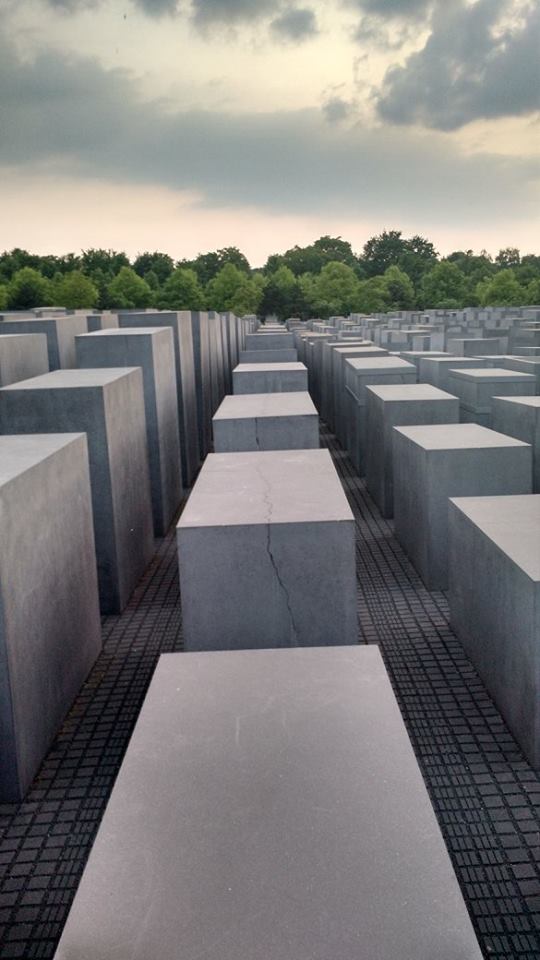

Larger monuments have gained international fame, but they remain part of the city where Berliners work and live. One of the better examples is the “Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas” or the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.

Berlin's Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.

Simple in concept if not in scale, the memorial is comprised of nearly 3000 concrete slabs arranged in rows that gradually become taller and more imposing the deeper the visitor wanders into the center. Berliners respect what the monument represents but it does not stop them from using the slabs as a place on which to rest or play, which often confuses visitors who are unsure about the appropriate boundaries for interacting with a memorial.

A memorial to Holocaust victims in front of a Jewish cemetery.

The events following the Second World War thrust Berlin onto the international stage in a new way during the Cold War. The standoff between the two world superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, was centered in Berlin. The country was famously divided into East and West Germany, but Berlin, deep in eastern territory, was considered too symbolically important to be surrendered to Soviet control. Consequently, Berlin was also divided between east and west, a partition literally cemented into place by the Berlin Wall in 1961.

A message of universal peace displayed on a portion of the Berlin Wall.

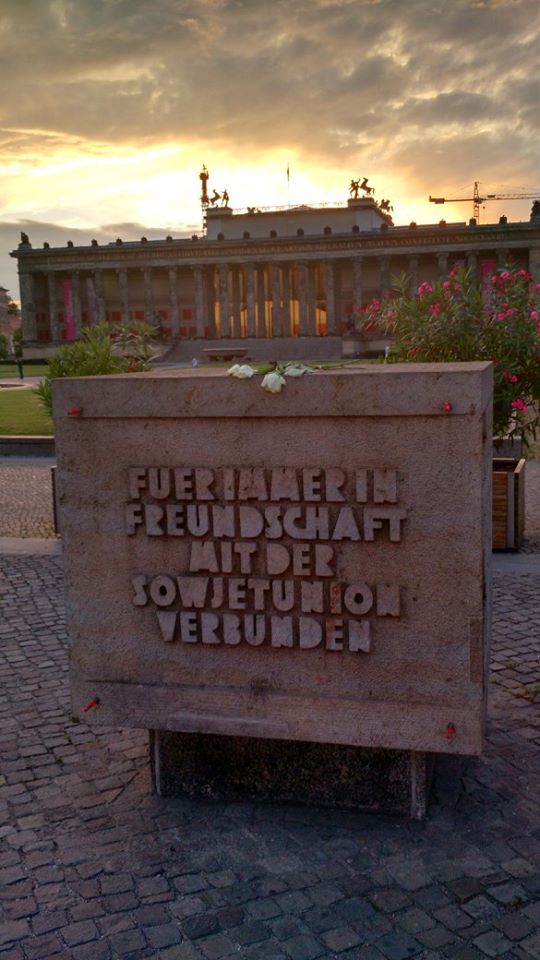

The way Berlin remembers the Cold War era is complicated. At one level, there is a nostalgia, pithily termed “Ostologie,” for the ideological values, and for the culture and products of the former East Germany, and small commemorations of the longer communist past are not hard to find. Streets and subway stations bear the names of communist German leadership from the Weimar era, statues of Karl Marx stand unharmed, and streets are still named for Friedrich Engels.

A small monument declaring eternal friendship with the Soviet Union.

On the other hand, there are monuments to the victims of the division, including large pieces of the Berlin Wall itself. The city honors ordinary people who died trying to cross the border as well as those who suffered at the hands of East German police.

A piece at the East Side Gallery depicting the number of years the Berlin Wall stood. The bolder numbers indicate deaths as a result of the partition.

Berliners mark the past by linking its lessons to the present, making their opinions known to the city and the world through street art. Berlin’s renowned graffiti speaks volumes about the attitude of residents remembering the past and connecting it to contemporary issues. Occasionally graffiti is clearly just meant to be bizarre or shocking, but more often than not it has a political goal.

Typical street art in Berlin.

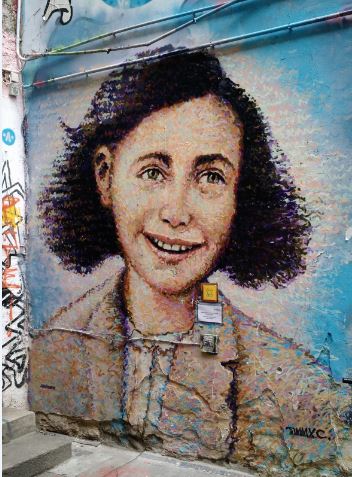

Street art goes beyond simply condemning Nazis and proclaiming “Never Forget” in a bold font. Art for Berliners captures the viewer’s attention and makes them consider what they are looking at.

Graffiti depicting Ann Frank celebrating what would have been her 87th birthday.

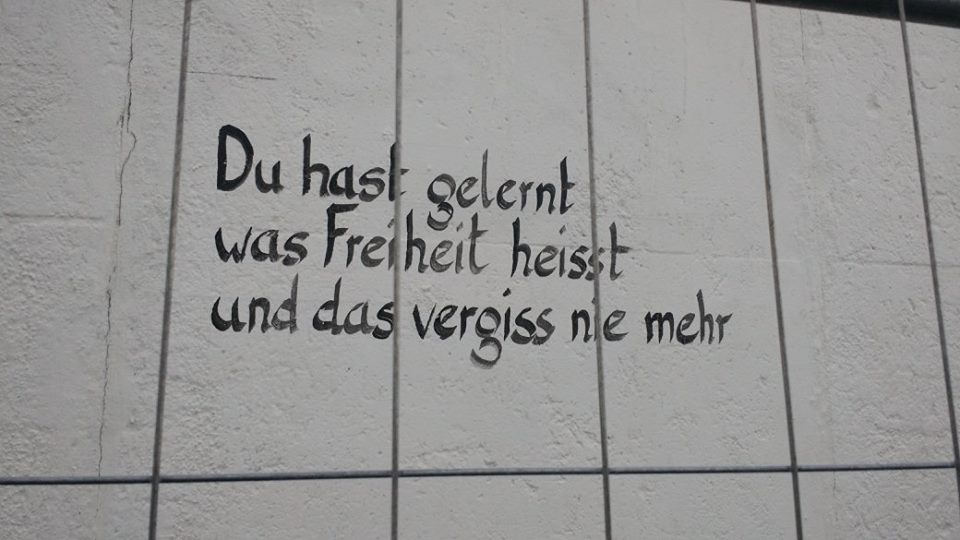

The meshing of politics and the past is perhaps best represented in the East Side Gallery, a public display meant to mimic a segment of the Berlin Wall. The art, ranging from poetry describing the cost of freedom to famous images such as the so-called fraternal kiss between Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker, usually convey a political message: peace no matter the price. This theme repeats itself on remaining sections of the Berlin Wall, with symbols of peace and personal appeals for love and understanding appearing in abundance.

A poem painted at the East Side Gallery. It roughly translates to: “You have learned what freedom means and will forget no longer.”

The infamous Fraternal Kiss (also referred to as “My God, Help Me Survive This Deadly Love”) immortalized both as a photograph and work of art. Found at the East Side Gallery, Berlin.

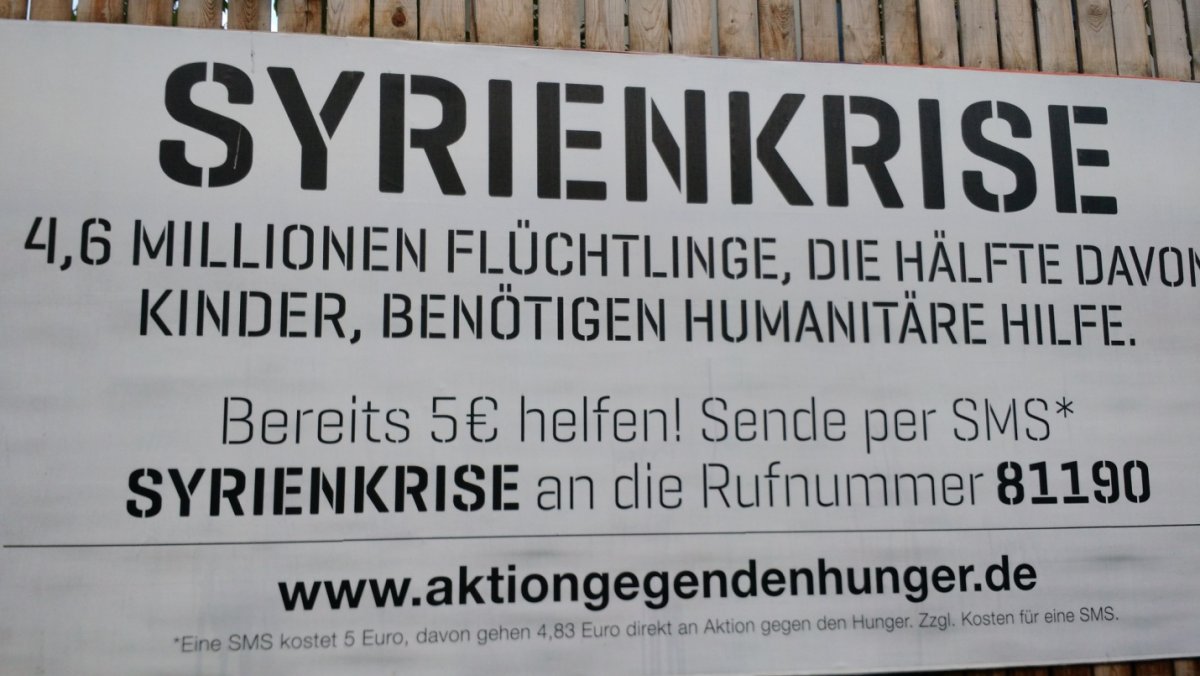

The most recent topic of controversy to be depicted on the city’s walls is the Syrian refugee crisis. Many European countries have been hesitant to accept the massive influx of desperate Syrians, but the mood in Berlin, as expressed by its artists, is one of elation to demonstrate their ability and willingness to accept and care for people in need. “Refugees Welcome,” a phrase repeated in all shapes and sizes throughout Berlin, is a small but consistent reminder of the German eagerness to help those affected by political violence.

A sign urges Berliners to donate in order to help feed Syrian refugees.

Graffiti on the Spree River welcomes Syrian refugees to Berlin.

The balance between the past and present can be tricky for any city, and Berlin is no exception. The city is a shrine to the triumphs and tragedies of German history, but also a space for millions to work, play, and live. Ultimately Berlin belongs to Berliners; but its monuments, its lessons, and most importantly its history, belong to the world.

A surviving section of the Berlin Wall in Potsdamer Platz, Berlin.

[All photos by author]