Since 1890, May 1st has been celebrated as International Workers Day.

So declared the International Socialist Congress meeting in Paris in July 1899. The comrades set the date in solidarity with organized workers in the United States, where the fledgling American Federation of Labor had scheduled the upcoming May 1 to initiate a drive for the eight-hour day. The date stuck for workers of the world—except those in the United States.

In honor of May 1, here are ten of the most important moments in American labor history.

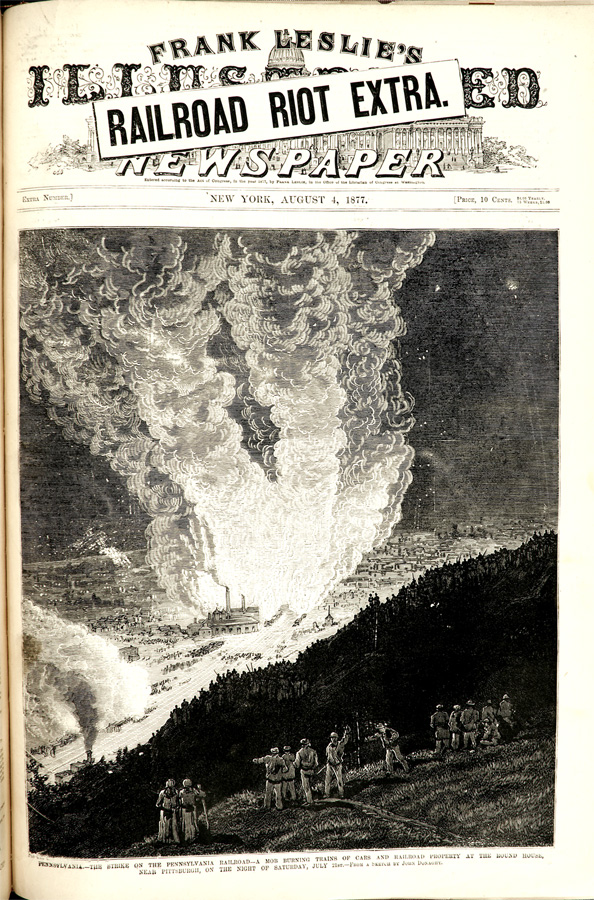

1. The Great Strike of 1877

Workers burning railroad property in Pittsburg during the Great Strike of 1877.

The Great Strike of 1877— America’s first nationwide labor conflict—was but the opening salvo of nearly two decades of constant labor-capital conflict. From the Panic of ’73 through the serious collapse of ’93, agricultural overproduction in an era of monetary inflexibility put constant downward pressure on prices and wages, and the first large waves of immigrants from Europe put additional strain on labor markets.

On July 16, 1877, a lone firefighter on Engine 32 of the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) railroad walked off the job. That spontaneous act of defiance set off a wave of worker rebellion that ran along the B&O from Maryland to West Virginia, north into Pennsylvania and westward through the Midwest.

Eventually, the Great Railroad Strike reached from coast to coast and moved even into the South. By the time the unrest cooled, at least 80,000 railroad workers and hundreds of thousands of other laborers took part. More than 100 people died in the various clashes between workers and the forces of order.

The 1877 Strike began for a very specific reason: a series of successive wage cuts the B&O imposed since the depression of 1873. But, the underlying source of antagonism was the loss of the ideal of worker autonomy in the face of large operations under the control of corporations. By 1880, corporations employed some seventy percent of non-farm labor. Those striking workers were perhaps justified in thinking they were striking not just against recent wage cuts but an entirely new form of “wage slavery.”

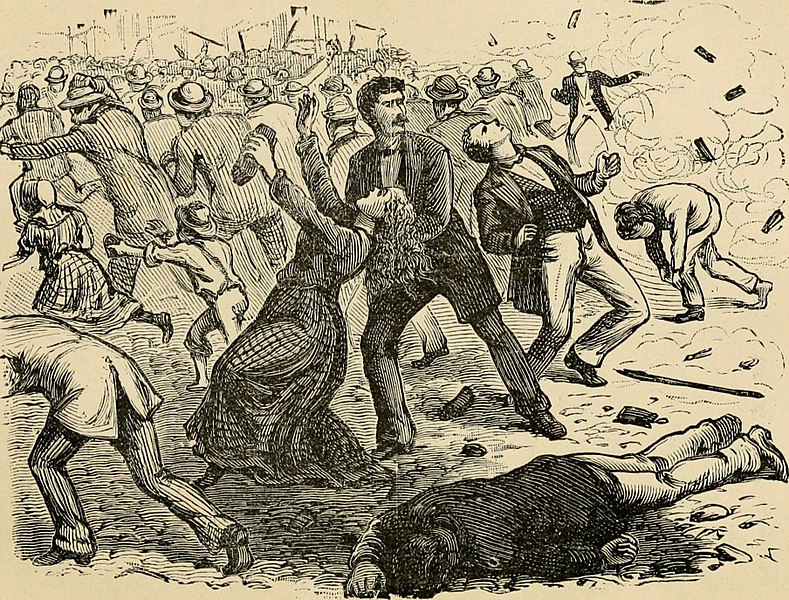

2. Haymarket Square, 1887

An 1886 engraving of the Haymarket Affair (left). Portraits of the “Haymarket Martyrs” widely circulated among anarchists, socialists, and labor activists in the 1890s (right).

The rallying cry across the field of organized labor in the 1880s was “the eight-hour day!” Along with low wages and abusive employers, many jobs went from ten to eleven hours each day. American workers—especially those in Chicago, America’s booming industrial hub—were fed up.

Fueled by the growing influence and power of anarchists, socialists, and the Knights of Labor, workers heeded a call by Samuel Gompers’ Federation of Organized Trades for demonstrations nationwide for an eight-hour day on May 1, 1886. That day, thousands of workers struck in Chicago.

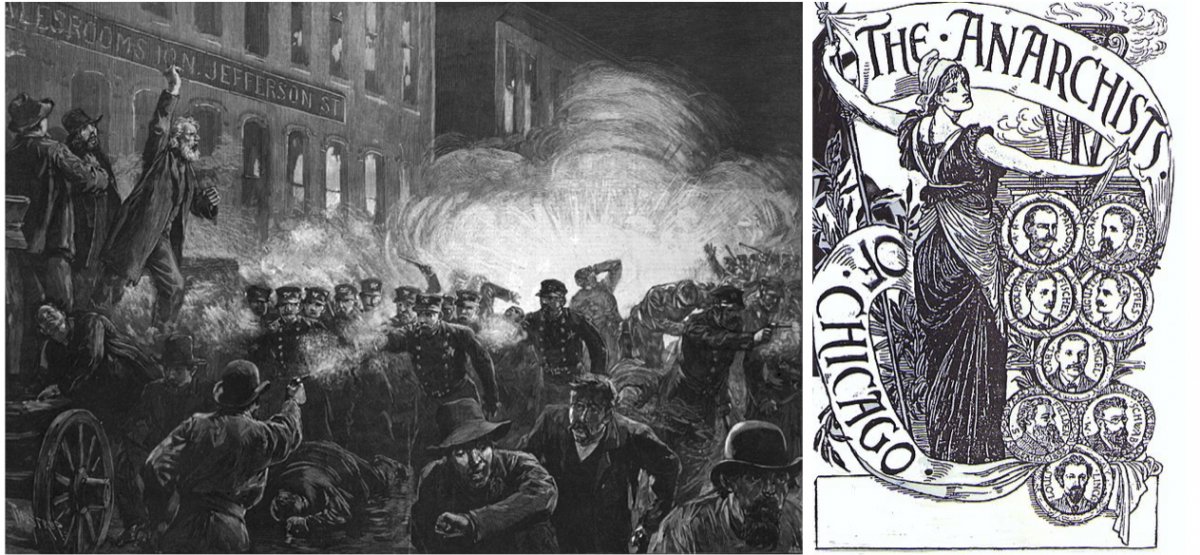

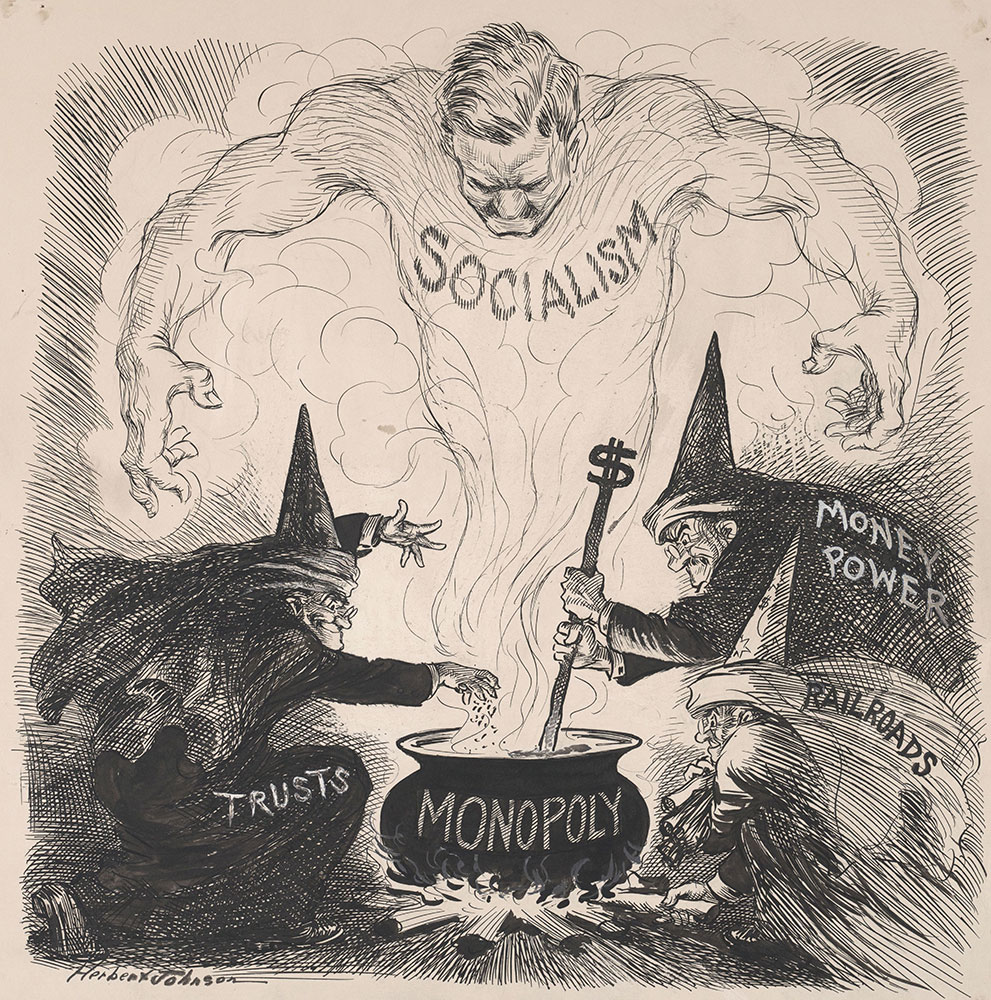

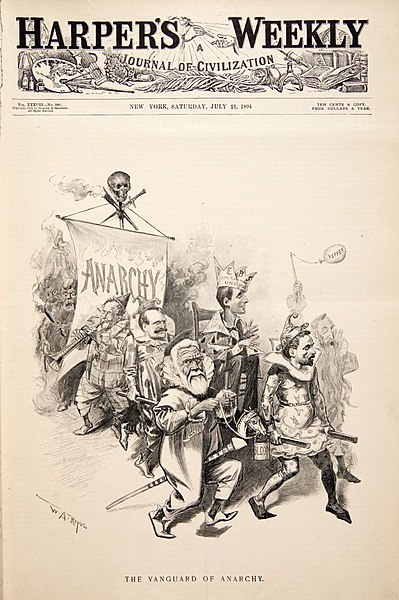

A political cartoon showing the forces that led to the rise of socialism.

On May 3, workers at McCormick Harvesting Machine Company were locked out after the notoriously anti-union company moved to replace iron molders with molding machines. Violence broke out, and the Chicago police shot and killed four workers and beat dozens of others.

The next evening police rushed a labor rally in Haymarket Square; at least thirty people were wounded and three killed by police gunfire. But a bomb placed in the crowd killed seven police officers. Ten anarchists were indicted for conspiracy to commit murder, based on cooked-up evidence and claims that anarchism and socialism were un-American. All the men but one were sentenced to death.

3. The Pullman Strike, 1894

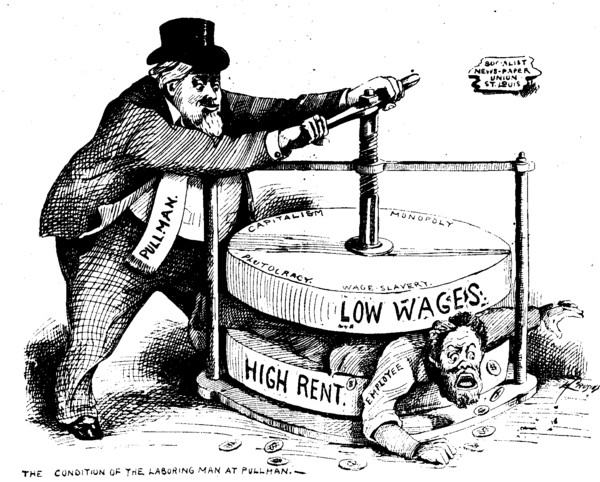

An 1894 cartoon depicting the pressures on workers.

Chicago was the prototypical industrial city. As of the 1890 census, some 3,000 firms employed a third of the city’s 360,000 laborers. Seventy-five percent of the city’s population was foreign-born or children of foreign-born parents.

The Pullman Railcar Company, which enjoyed a near monopoly in the production of luxury rail cars, pulled its largely immigrant workforce into a “company town” on Chicago’s south end. Pullman owned the houses, the opera house, the grocery store, and paid its employees in company script.

When Pullman tried to meet the pressures of the severe depression of 1893 by cutting wages but not rents, the workers organized themselves into a strike in May. They did so against the advice of the American Railway Union (ARU), led by a thirty-nine-year-old rabble-rouser from Indiana, Eugene V. Debs. They pulled the union along, however, and Debs’s vision of a national union received an enormous boost when members threw their support to the Pullman strikers by refusing to handle Pullman cars.

An 1894 political cartoon showing Eugene Debs as the crowned leader of the Pullman Strike.

Stubbornly refusing to meet with the ARU, company president George Pullman appealed to the conservative Democratic president Grover Cleveland. Cleveland’s attorney general, himself a railway lawyer by trade, declared the strike in violation of the recently passed Sherman Anti-Trust Act on the grounds that the boycott acted in “undue restraint of trade.” A law created to address the problem of monopoly was invoked in support of capital.

The use of federal legislation to circumscribe labor organization marked a dramatic confirmation that the state was aligned with the interests of business. If the state was determined to guarantee capital untrammeled freedom to abuse workers, Debs repeatedly said, then the only course for workers was to seize the state.

4. The Uprising of the 20,000, 1909-11

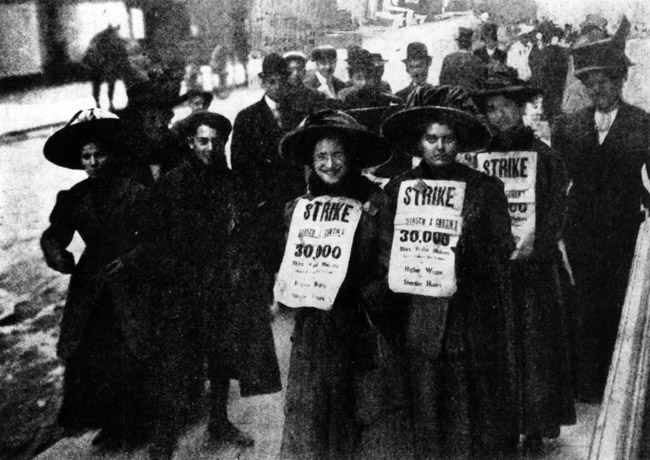

Striking workers demanding higher wages and shorter hours in 1909.

If the Pullman workers demonstrated that class-conscious solidarity across ethnic lines was possible, the young shirtwaist makers who threw New York City into chaos in November 1909 demonstrated that gender was no barrier to labor radicalism.

The fifteen to twenty thousand strikers who demanded that employers recognize the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) as well as higher wages and working conditions were virtually all women, the vast majority foreign-born. Arrested on bogus charges, roughed up by hired thugs and police, the women filled the courts. In the course of the uprising, the strikers found support from elite reformers in the Women’s Trade Union League as well as members of New York’s high society.

Some employers broke ranks and settled with the ILGWU. Others, particularly the owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, stubbornly outlasted the strikers. A little more than a year later, fire ravaged the Triangle Shirtwaist factory and killed 142 workers in the single greatest workplace tragedy in American history—until the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Together, the Uprising and the Triangle fire impelled a series of state laws that governed worker safety and working conditions for women and children.

5. Red Interlude, 1919

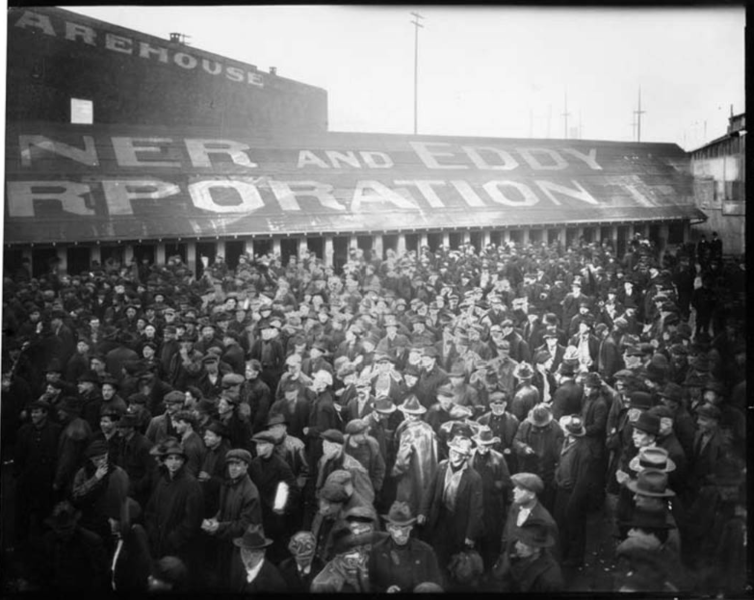

Strikers outside a Seattle shipyard in 1919.

When World War I ended, a toxic mix of abrupt demobilization and anti-Bolshevik and anti-immigrant hysteria created an atmosphere of deep hostility to worker activism. When workers tried to preserve hard-won gains, an entire year of upheaval ensued. New York harbor workers welcomed the New Year with a January strike. In February, over 90% of Seattle’s unionized workers launched a general strike that gave them control of the city for a week. State militia restored the status quo, but the Pacific Northwest remained a hotbed of labor radicalism and anti-radical reaction.

The two came together in Centralia, Washington in November when a mob attacked the meeting hall of the International Workers of the World, killed four Wobblies (as members of the union were known), and lynched a WWI veteran, Wesley Everest. In late summer, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) staged a massive walkout across the Great Lakes steel belt.

Seattle police setting up a machine gun during the general strike in 1919.

Boston police eating together during the 1919 strike.

A week after the steel strike began, the mostly Irish-Catholic Boston police, who hadn’t had a raise since before the Civil War, struck when the Brahmin city fathers refused to recognize a union and suspended officers who had been organizing under the AFL. Authorities quickly brought in state militia and the Harvard football team to preserve order.

During the high point of the year’s labor unrest, more than a million workers were simultaneously on strike. It was the largest eruption of labor conflict in American history. Yet across the board, workers lost their fights. Without the war, they had no leverage.

6. The Coal Wars, 1931-39

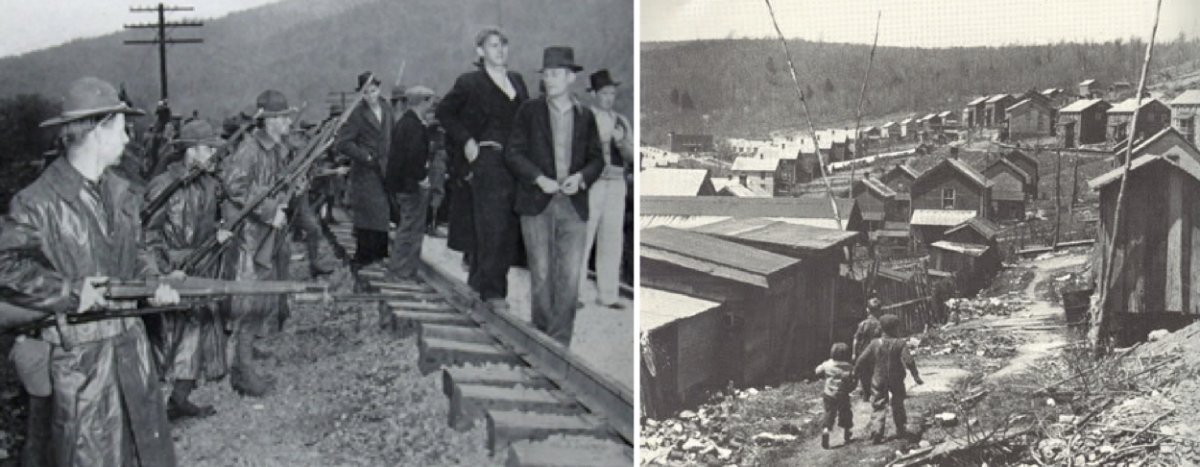

Guards keeping strikers at bay in Harlan County in 1937 (left). Harlan County miner’s homes in the 1930s (right).

The most significant industrial labor conflicts took place in cities between 1890 and 1930 and involved immigrant workers. Yet, rural, native-born workers labored in chronically depressed industries such as textiles and coal—the so-called “sick industries” of the 1920s.

Living conditions were so wretched in the bituminous coal regions of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Kentucky by 1930 that the Red Cross began emergency relief efforts. The Appalachian miners were, as novelist John Dos Passos described them, “of old American pre-Revolutionary stock” who “still speak the language of Patrick Henry and Daniel Boone.” They were disinclined to slink away from violence.

Harlan County miners in the 1940s.

When the coal companies moved to squash any efforts to revive unions by employing company police, big-city gangsters, and corrupt public officials, the miners responded in kind. The result was nearly a decade of intermittent warfare, with “Bloody” Harlan County, Kentucky as its epicenter. Miners attempting to organize in 1931 fought running battles along the roads; the state’s governor called in the National Guard after miners killed four company men and wounded many others.

While the United Mine Workers, led by the magisterial figure of John L. Lewis, secured union recognition under New Deal protections, Harlan operators resisted through the strike of 1939, when four union miners were killed and several wounded in gun battles with company guards. The coal wars ended only when World War II brought prosperity and union recognition to the coalfields.

7. The Flint Sit-Down Strike, 1937

Strikers outside a GM plant with police standing guard in Flint, MI in 1937.

Under Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, organized labor received its first peacetime legislative protections. The 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA) guaranteed the right to uncoerced organizing and collective bargaining; when the Supreme Court declared the NRA unconstitutional in 1935, congress then passed the National Labor Relations Act (the Wagner Act), which reestablished organizing rights and created a mediation process.

The United Auto Workers (UAW) saw a window of opportunity to organize the auto industry after the 1936 election brought a Roosevelt landslide and, more important for them, the election of a sympathetic governor to Michigan. On December 30, 1936, shop-floor activists in General Motors Fisher Body plant No. 2 in Flint, Michigan occupied the plant to protest several recent firings. Because the plant made the body dies for virtually every GM car, they hit at one of the company’s most strategic choke points.

Strikers guarding the entrance to a GM plant in 1937.

Workers celebrating the end of the strike after 44 days.

Unable to persuade the new governor, Frank Murphy, to clear No. 2 and other plants where sit-downs took hold, GM security police and local police assaulted No. 2 in a hail of tear gas and bullets on January 11. Thirteen union men were wounded in “the Battle of the Running Bulls.” Governor Murphy dispatched the National Guard, but as a neutral peace-keeping force. Weeks of tense negotiations, the occupation of another strategic plant, and the governor’s continued neutrality finally brought GM to recognize the UAW in all its operations.

The Flint Sit-Down strike drew tens of thousands of workers into the union and generated organizing momentum through auxiliary firms in rubber, glass, and parts. It stands as perhaps organized labor’s most successful moment.

8. The 100-Day Chrysler Strike, 1950

UAW officials ensuring that workers had health insurance during the strike in 1950.

Though it lacked the drama of other entries, the Chrysler strike of spring 1950 was the second longest in the history of the auto industry and one of the most expensive. Its historical importance, however, rests in its results.

The strike ended on May 4 with a three-year contract for UAW workers that included a company-administered pension plan. A mere two weeks later, having seen the lengths to which the UAW was willing to go to secure an extended contract and increasingly interested in long-term stability, General Motors agreed to a five-year contract that included a pension plan and annual wage hikes.

Hailed as “The Treaty of Detroit,” this set of contracts, which soon spread across the industrial economy, established a labor-relations process that held for a quarter century. Long-term contracts seemed to lock organized labor into the mainstream of American life. For UAW president Walter Reuther, the Treaty of Detroit was the means to build a social democratic America.

But left-leaning critics like sociologist C. Wright Mills were wary of labor’s institutionalization, not least because it surrendered control over the processes of work and allowed management to undercut workers’ control of production through constant technological interventions.

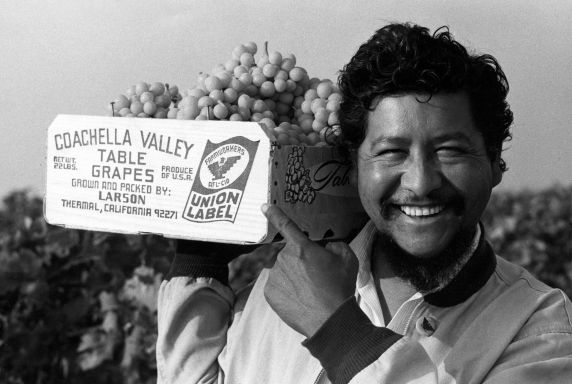

9. The Delano Grape Strike, 1965-70

Picketers supporting the grape strike and the United Farm Workers.

The long effort to win union representation for California farm workers demonstrated that the post-WWII prosperity of the United States missed entirely those at the very bottom of the labor system, and it showed as well how organically labor rights are connected to human rights and social justice.

The strike in September 1965 began when a group of Filipino grape pickers, following an experienced organizer named Larry Itliong, walked out of the fields surrounding Delano, California. Within weeks, Mexican farm workers, who had long competed with the Filipinos, followed suit. Because farm workers were never included under federal labor protections and because it remained easy to import Mexican workers even after the formal guest worker Bracero program ended in 1964, the growers ignored calls for negotiations.

Richard Chávez, the younger brother of César Chávez, celebrating the union label on a crate of grapes.

The emergence of a charismatic leader, César Chávez, gave the movement staying power. As the movement persisted, the growers used small-scale violence and intimidation against picketers and organizers. California Governor Ronald Reagan denounced the strike as “immoral” and dispatched state prison inmates to replace strikers.

Chávez shaped the organizing drive on the model of the non-violent civil rights movement and cultivated support from national figures like Robert Kennedy. In 1968, the United Farm Workers called for a nationwide boycott of California. They mobilized a constituency that, as a Boston Globe reporter found, brought together “Black Panthers and white housewives . . . doves and hawks, Resisters and politicians, professors and drop-outs, young and old.”

The strike lasted until July 29, 1970, when the growers agreed to $1.80 hourly wage, fringe benefits, and union recognition.

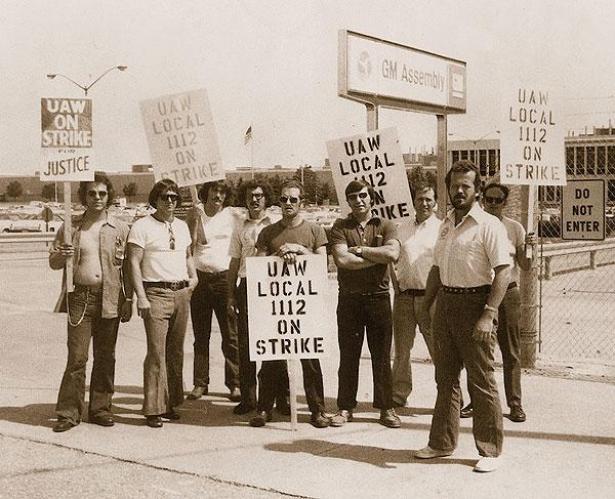

10. Lordstown Blues, 1972

UAW President Leonard Woodcock with a Lordstown, OH assembly line worker in 1970.

Like the 1950 Chrysler strike, the Lordstown, Ohio strike of 1972 was more important for what it symbolized than for any drama. Indeed, it closed the door on the Treaty of Detroit, which in retrospect was less a treaty than a truce. Even as the auto companies were signing on to long-term truces, they were using technological innovations to move plants to non-union sites while introducing automated processes that gradually reduced their need for labor.

The GM operation at Lordstown crystallized the drive for automated efficiency. In 1971, those “white shirt pocket[s]” of David Mamet’s poem (see below) installed the fastest assembly line in the world. Workers had thirty-six seconds to perform a task, which allowed GM to fire hundreds of “surplus” workers, all to produce the Chevrolet Vega, the worst American car ever made.

UAW strikers at Lordstown in 1974.

Workers called off sick, sabotaged vehicles, or simply let cars roll down the line without working on them. They choked the union grievance system with some 5,000 claims, many of which were directly related to the speed of the line, and, by early 1972, a strike appeared foreordained.

Nearly every observer of the strike pointed to the deadening nature of the work and the exhaustion of workers, most of whom were baby boomers who had been raised in the era of abundance, some of whom had served in Vietnam. They resented the de-humanized nature of the work, and they did not take orders well.

But Lordstown represented not the beginning of a new labor militancy, much less a new declaration of war against automation. Quite the opposite. It was a last gasp of resistance against the technological domination that became embedded in the globalized processes that have destroyed whatever was left of the working-class’s will to autonomy that drove those angry railroad workers in 1877.

David Mamet, Labor Day (1992)

The white shirt pocket puked Pencils and cigarettes.

The mailbox torso stuck on sausage legs,

He strode The Overpass,

Or took one during little Steel,

In the perennial red scare/that was the industrial age, until

Now not the Pinks, but the Tobacco,

Sent him to see Joe Hill.