On September 10, Indiana University President Myles Brand dismissed Indiana University's men's basketball coach Bob Knight, nicknamed "The General," for defying university officials and for violating a "zero tolerance" policy against his angry rages. Brand was criticized for his rash act against a national celebrity. Meanwhile, Knight complained that he was a victim of changing expectations that ended his hard-line leadership.

An Indiana trustee critical of Brand's action invoked a pointed comparison: "President Truman fired General MacArthur. President Brand fired General Knight." Defending Knight, the trustee compared Knight's firing to the earlier dismissal of a popular general by a chief executive — the firing in 1951 of General Douglas MacArthur by President Harry Truman.

But is the comparison valid? In fact there are noteworthy coincidences between the two controversies. Both MacArthur and Knight were admired for their success and self-confidence, and neither tolerated ambiguity in decision-making. Their leadership style led them to defy higher authorities. When those above them in authority risked public criticism and punished their defiance, both tried to manipulate the public by casting themselves as victims.

MacArthur was arguably America's greatest military field commander. In World War II he led the recapture of the Pacific islands from Japan. In July 1950 the Truman administration sent him to Korea after Communist North Korean troops launched a surprise attack on South Korea. There he devised a daring amphibious assault behind enemy lines that enabled United Nations forces to drive the North Koreans back. This tactic confirmed MacArthur as a "virtuoso strategist," said one analyst.

Like MacArthur, Knight too has been regarded as a strategic genius. His Indiana teams were feared because of their ability to exploit feared such discipline?

Yet the very nature of the success that the two men enjoyed led each to his undoing. Both preferred to operate without supervision. After United Nations troops occupied most of North Korea, Truman, MacArthur's commander-in-chief, ordered preparations to negotiate peace. Instead, after Chinese intervention forced an ignominious retreat to the south, MacArthur tried to widen the war, pleading for American use of the atomic bomb. In an inflammatory letter to Congress, he declared, "The Communists have elected global conquest. We must win. There is no substitute for victory." Accustomed to autonomy, MacArthur ignored presidential authority and pleaded his case outside the chain of command.

Knight also created a virtual fiefdom, free from administrative interference. Indiana, said an opposing coach, was the one institution where the basketball coach was larger than either the basketball program or the university itself. Neither the university president, nor trustees, nor alumni would accept tampering with a coach so embraced by a basketball-loving state. They were seduced by success. Much as MacArthur won victory in the Pacific, Knight coached Indiana to three national titles and eleven Big Ten championships.

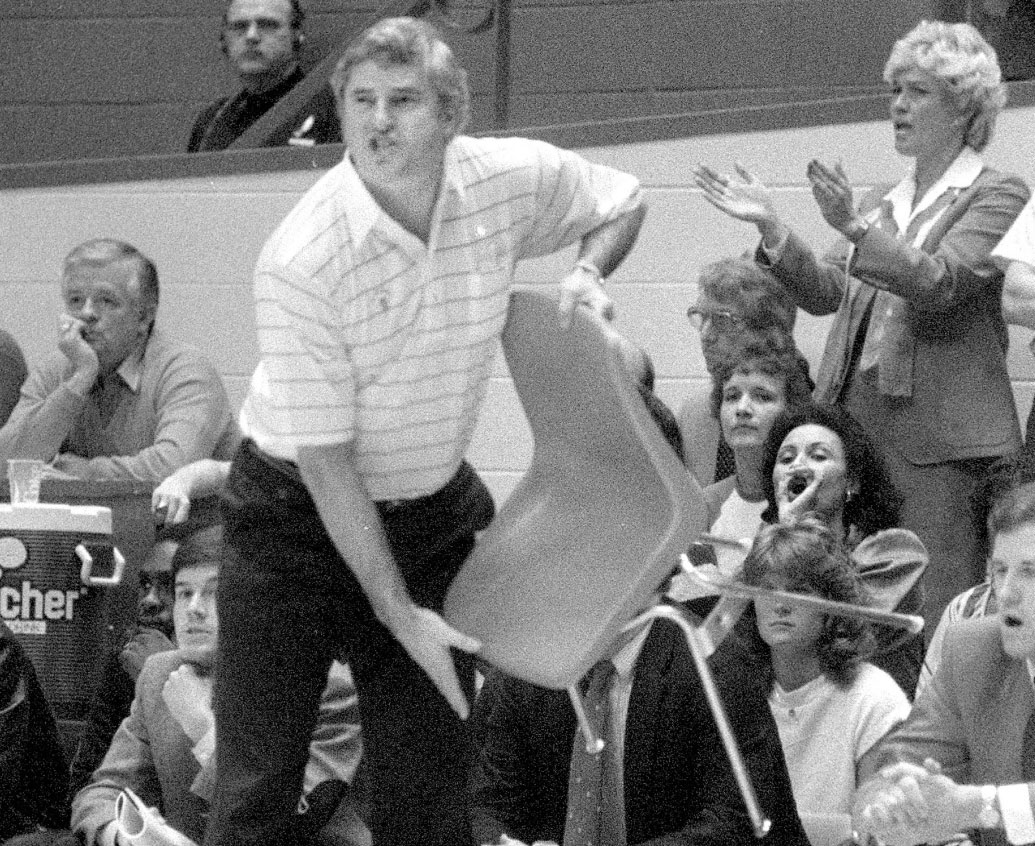

But in the midst of championships, Knight was verbally and physically abusive of fans, police, players, secretaries, referees and reporters, and was antagonistic toward Indiana University's administration. Within his domain he became a tyrant, and threatened the reputation of the entire university.

Despite MacArthur's immense popularity with the American people, Truman recalled him from Korea in April 1951. The general's removal provoked an uproar. Congressmen and newspapers called for Truman's impeachment, while American people burned the president in effigy. MacArthur addressed a joint session of Congress, whispering that he was interested only in doing "his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty." He visited New York City, where 7.5 million people gathered to cheer him.

The removal of Knight also created a firestorm, rating him a page-one story in The New York Times and a national interview on ESPN. In support of Knight, students rioted in Bloomington and burned Brand in effigy. Brand's administrators and his family were harassed. Knight has remained unrepentant, pleading that he is only a misunderstood teacher of the game of basketball.

Each in his day, MacArthur and Knight displayed a stubbornness that captured the nation's imagination. During the 1950s anti-Communist fears were widespread, and MacArthur's refusal to negotiate with an enemy that he regarded as evil won over an American public not ready to strike deals. Similarly, the image of Knight rebuking prima donna players, irritating reporters and even roughing up foreign policemen struck a chord with American fans. Both men refused to compromise their principles — even when their principles pushed them to their self-destruction.

What one observer said of Knight applies to both men: "He has a potent mix of high competence with characteristics that cause him to sabotage himself. That's a fascinating thing — in a kind of morbid way – for people to observe."

Tim Roberts is an assistant professor of history at Western Illinois University. He is the author of Distant Revolutions: 1848 and the Challenge to American Exceptionalism (Virginia, 2009).