In Ethiopia, 2019 feels like a long time ago. That fall Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali won the Nobel Peace Prize. Ethiopia is now wracked by a vicious civil war and some blame Abiy Ahmed Ali for it. This month, historian Kim Searcy traces the roots of this latest outbreak of violence to the early 20th century and the fitful experiences Ethiopia has had creating a centralized government that works for all Ethiopians.

The conflict in the northern Ethiopian province of Tigray entered its second year in November 2021 with no end in sight. Opinions have polarized concerning why the conflict continues. Many blame Abiy Ahmed Ali, prime minister of Ethiopia and Nobel Peace Prize laureate of 2019, for not only instigating the conflict but for stoking its fires long after they should have burned out. Some of the prime minister’s detractors have labeled him a hypocrite, undeserving of the Nobel Prize.

Abiy Ahmed Ali accepts his Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, 2019.

When Abiy assumed leadership of Ethiopia, a country of 110 million people and more than 80 ethnic groups, he delivered a speech emphasizing reconciliation, love, and peace. At his inaugural ceremony in 2018, he counseled a complete break with the past forms of governance that were autocratic, arbitrary, and steeped in ethnic politics. He released political prisoners, ended restrictions on the press, and invited banned opposition groups to return.

The Nobel committee was most impressed that he made peace with Eritrea. But his critics maintain that Abiy failed to deal with so-called extremists within his own Oromo ethnic community. He has given free rein to ethnic separatist groups to run roughshod over the country, and the most egregious act of these groups has been to launch a military campaign against the Tigray province in northwestern Ethiopia.

According to these critics, federal forces, ethnic militias, and allied troops from Eritrea are responsible for rapes, massacres, and the displacement of two million of Tigray’s six million people. Furthermore, journalists have been banned and phone and internet services have been severed in the region.

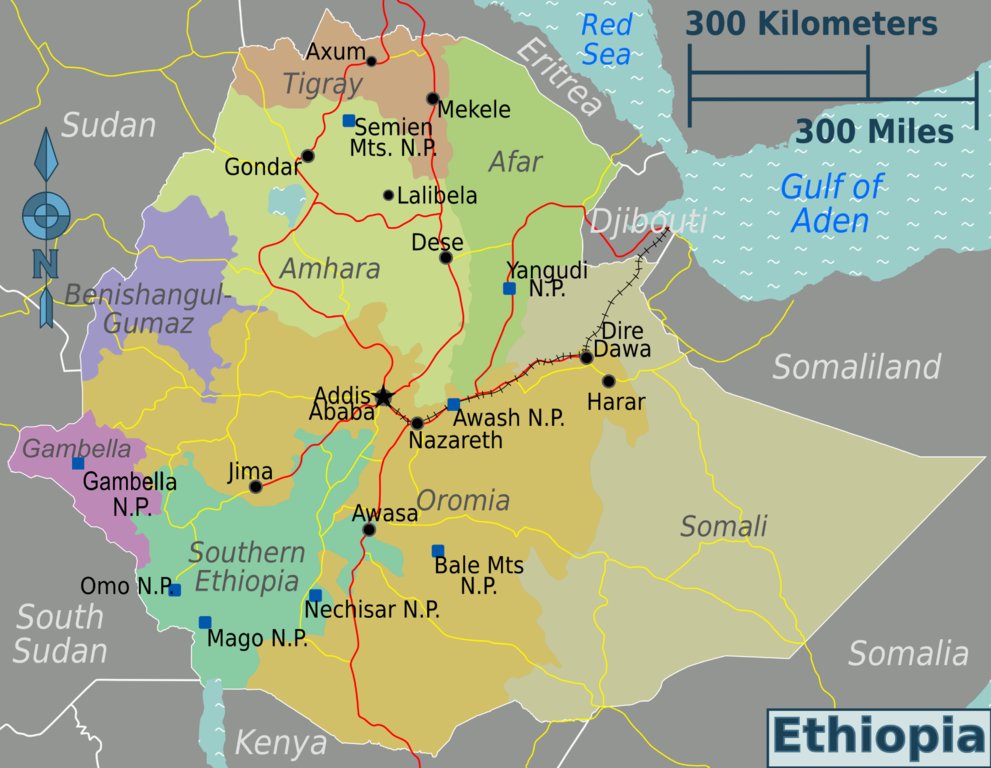

Map of Ethiopia’s regions. Tigray can be found in the northwest of the country.

Throughout the war in Tigray, accusations have been leveled against Abiy that he is preventing deliveries of food and humanitarian assistance. The United Nations reported that many farms have been destroyed. Seed and livestock have been lost. “Without humanitarian access, an estimated 33,000 severely malnourished children in currently inaccessible areas in Tigray are at high risk of death,” according to a UN report.

Additionally, charges of ethnic cleansing have been leveled against the prime minister and the central government. Amnesty International released a report in April 2021 maintaining that Eritrean soldiers fighting with Ethiopia had killed hundreds of Tigrayan civilians in the city of Axum over a ten-day period in November 2020.

An Ethnic History of Ethiopia

Ethiopia is a multi-ethnic and multi-religious country. It lays claim to being one of the oldest Christian countries in the world, but the number of Christians equals the number of Muslims there.

Ethiopian nationalism has its foundations in cultural and political symbols from the northern highlands of the country. These highlands are dominated culturally by the Semitic-speaking Amhara and Tigrayan peoples (Tigrayans constitute about six percent of Ethiopia’s population today).

Tigrayan men at a church in Axum, 2013.

The states in the highlands claim a continuous tradition stretching back to the kingdom of Axum in the medieval period and further back into antiquity. Until 1974, for example, the emperors of Ethiopia claimed to be direct descendants of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. These emperors were anointed by the Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Until the mid-twentieth century, the state was known as Abyssinia. The northern highlands of Amhara and Tigray are called “habash,” which has the same derivation as Abyssinia.

Some argue that the peoples of the southern provinces of modern Ethiopia, specifically the Oromo people who are the largest ethnic group in the country, are not a core community to Ethiopian civilization. The Oromo have been labeled as invaders, and conversely some Oromo consider the Amhara as colonizers.

Oromo villagers in the Oromia region of Ethiopia, 2014.

Yet, others contend that the homelands of the so-called Oromo invaders fall within the boundaries of modern Ethiopia and that a reading of history that excludes them from Ethiopian history promotes an ethno-centric bias that favors the northern highlands version.

Deep Roots of the Tigray Conflict

The conflict in Tigray erupted in September 2020 when the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which was the ruling party of Ethiopia for almost three decades, refused Abiy’s directives by holding elections that had been canceled in the rest of the country because of the coronavirus pandemic.

According to Western officials, Abiy launched an attack against Tigray as a punitive measure for defying his orders. Abiy, for his part, accused the TPLF of initiating a military assault on the Northern Command army headquarters in the Tigrayan capital of Mekelle to obtain artillery and other weapons.

However, the roots of the conflict are much deeper and inextricable from the modern history of Ethiopia.

Prior to 1855, Ethiopia was a country divided, with no powerful central authority. This period, which began around 1769, is known in Amharic as the Zemene Mesafint, which is translated as the “Age of Princes.” During this time the Ethiopian emperors were only figureheads, “ruling” from the capital city of Gondar. Numerous noblemen held de facto power.

There was constant warfare among the noblemen over land and authority to crown the emperor in the capital. The fighting ended when the Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855-1868) began a concerted effort to unite the country under his rule and end the decentralized Zemene Mesafint.

An illustration of Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia surrounded by lions, 1875.

A succession of three emperors and one empress followed the reign of Tewodros from 1871 to 1930, including the first female head of state of an internationally known African country, the Empress Zewditu (r. 1916-1930).

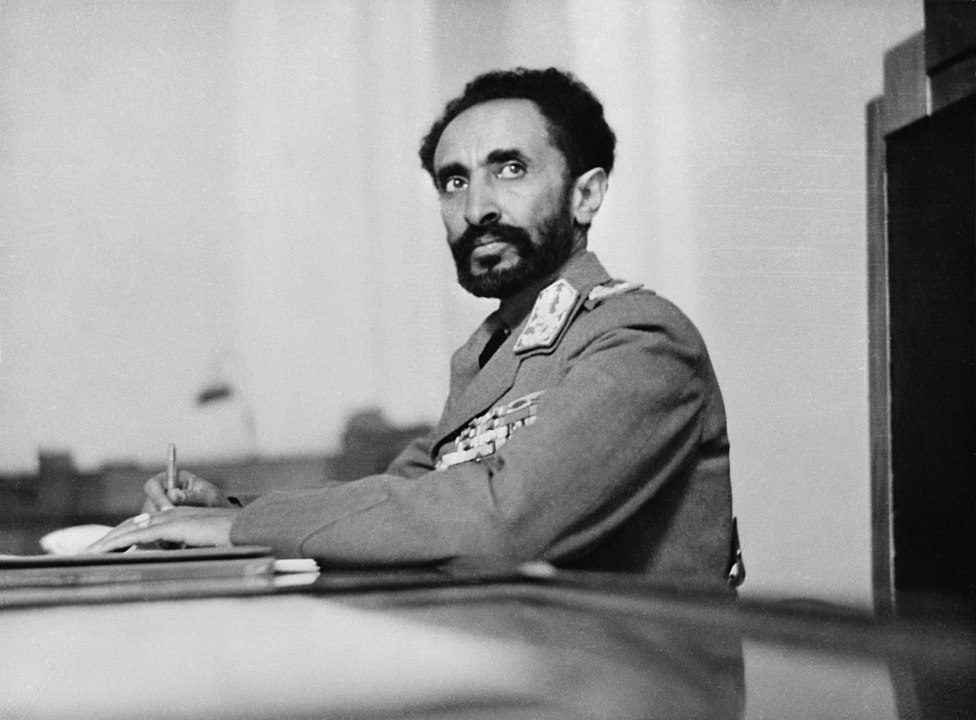

The last and most famous Ethiopian emperor was Haile Selassie (r. 1930-1974). His predecessors had failed to unify Ethiopia, so Selassie’s great achievement, as Ethiopian historian Bahru Zewde has observed, was finally “realizing the unitary state of which Tewodros had dreamed.” Power was concentrated in the hands of the ruler who governed from the capital Addis Ababa.

However, by 1935 Tigray was the one region still largely outside the control of the central government. In 1941, Selassie attempted to centralize power even further and weaken the power of regional elites, which in Tigray entailed dividing the region into eight counties. Many in Tigray resented the change because Selassie was taking power from the hereditary elites in Tigray and concentrating it in the hands of Shewan/Amhara elites.

In May 1943, Tigrayan rebels launched an insurgency called Woyane, a term denoting resistance and unity. The insurgency was crushed in November of 1943 with forceful assistance from the British Royal Air Force. Selassie requested that the RAF bomb two Tigrayan towns, the capital Mekelle and Corbetta.

Emperor Halie Selassie in 1942.

According to scholar Yohannes Woldemariam, this alliance “left a deep scar in the psyche of Tigrayans.” A second Woyane developed into a 15-year war the TPFL waged against the Derg regime (1974-1991). The third Woyane is the current conflict in Tigray.

The Origins of the TPLF

Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935. Selassie led the resistance against this colonial expansion and was forced into exile in May 1936 after Italy proved victorious. He sought refuge in England and appealed to the League of Nations. In 1941, combined Ethiopian and British troops recaptured Addis Ababa, and Selassie was reinstated as emperor.

In 1955, he created a new constitution that consolidated his power and authority over the country. However, his rule was challenged when a section of the army took control of the capital in December 1960. This coup attempt was put down with assistance from loyalist elements of the army. However, this military challenge signaled the beginning of the end of Selassie’s grip on power.

The political stagnation of the government, coupled with famine and increasing unemployment emboldened members of the army to organize a military takeover of Ethiopia in 1974. These segments of the army deposed Selassie and established a military government, known as the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army.

Popularly known as the Derg, which is Amharic for committee or council, the new regime dismantled the monarchy’s institutions, arrested loyalists and supporters of the emperor, and refashioned Ethiopia into a Marxist-Leninist state.

Mengistu Haile Mariam became chairman of the Derg in 1977. Given complete power, he launched a campaign known as the “Red Terror” and eliminated political opponents by either imprisoning or summarily executing them. Behind the motto “Ethiopia First,” Mengistu took a rigid stance against any ethnic or regional divisions as threats to Ethiopian unity and interests.

“Ethiopia First” destroyed any hope that Mengistu would address Tigrayans’ plight, and a number of ethno-nationalist groups willing to take up arms against the Derg emerged in the 1970s. The Tigray University Students Association (TUSA) was formed in the early 1970s to persuade parliamentarians, businesspeople, and other Tigrayan leaders to improve the situation in Tigray.

In September 1974, the Tigrayan National Organization (TNO) spun off from the student group, and in February 1975, the TNO became an armed movement known as the TPLF. The initial founders of the TNO were seven university students who drafted a mission statement that sought to use armed struggle to bring about the “formation of a democratic Ethiopia in which the equality of all nationalities and ethnicities is respected.”

A simplification of the Tigray People's Liberation Front's flag.

In its initial armed resistance, the TPLF fought and defeated two rival groups in the province: in the west, a large group comprised of the former nobility (who were intent on reestablishing control of the lands); in the east, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party, a student-led socialist movement.

By 1979, the TPLF was the only important opposition movement in Tigray, opposed to centralizing efforts from Addis Ababa. Nationalism and self-determination were at the core of the Front’s ideology and agenda. Ultra-nationalists within the TPLF early on sought secession from the Ethiopian nation-state, a minority position that was soon discarded.

The TPLF and the EPLF

In its earliest inception, TPLF was given a great deal of assistance by the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), which at that point had waged 15 years of armed struggle for independence against the Ethiopian government. The EPLF support for the TPLF was contingent upon the latter accepting the position that Eritrea was a colony and had a right to secede from Ethiopia.

Linguistic and cultural similarities reinforced shared political interests, and consequently, the groups united in the late 1970s against their common foe, the Derg. Tigrayan peasant recruits were trained by the EPLF. As the TPLF grew in strength and experience, the Mengistu regime was forced to send more troops to defend Tigray at the expense of its fighting on the Eritrean front.

From 1985 to 1988, the TPLF army was reorganized, and its forces increased with the founding of the Ethiopian People’s Democratic Revolutionary Front (EPRDF), a coalition of ethnically based parties under TPLF domination (including representatives from the Amhara, Oromo, and southern ethnic groups).

Broadened and emboldened, the TPLF began to destroy larger targets within Tigray instead of merely engaging in guerrilla tactics. In 1991, the TPLF successfully defeated the Derg, thus ending 16 years of military struggle and bringing to power the EPRDF coalition.

The EPRDF Gains Power

When Meles Zenawi, a founding member of the TPLF and leader of the EPRDF, became the head of state of the new Ethiopian government in 1991, it heralded the rise of the oft-marginalized Tigrayans. His ascendancy demarcated a shift in power between ethnic groups and the new Tigrayan-dominated government instituted ethnic federalism. This form of governance divided the country along ethnic lines into nine regional semiautonomous states and two multiethnic chartered administrations.

The EPRDF controlled Ethiopia for almost three decades and arguably became the largest and most powerful political party in Ethiopia, if not the entire continent of Africa. Still, the TPLF dominated the party, even as the EPRDF claimed to provide equal representation to all its constituents.

Some scholars have argued that the TPLF ruled Ethiopia,” in the words of Girma Berhanu, “as one of the continent’s most autocratic regimes: its resumé includes political persecution, outright ballot-rigging, widespread corruption and two full-scale wars in just over a decade: against Eritrea in 1998-2000, and in Somalia in 2006-2009.”

TPLF resistance to meaningful change generated popular demonstrations for three consecutive years and paved the way for Abiy’s election in April 2018.

In November 2019, Abiy created the Prosperity Party, which brought together three of the four ethnic-based parties that made up the EPRDF coalition and five other smaller parties that had been marginalized in the past. The TPLF refused to join the Prosperity Party, thus ending the EPRDF’s grip on power in Ethiopia.

Abiy’s Challenges

Abiy created the Prosperity Party ostensibly to mitigate and ultimately eliminate the ethnic tensions that had been plaguing the country for years. In his book Medemer, which in Amharic literally means addition and is often translated or interpreted to mean “coming together,” Abiy emphasizes national unity in spite of the ethnic divisions. “We need a sovereign and Ethiopian philosophy that stems from Ethiopians’ basic character that can solve our problems. . . [and] that can connect us all.”

Unity proved elusive, ironically in part because Abiy’s move toward more progressive and open politics (such as eliminating vestiges of the previous authoritarian regime) actually emboldened ethno-nationalists in Ethiopia. Even young Oromos, individuals from Abiy’s own ethnic group, protested against medemer.

Less than two months after Abiy’s installation as prime minister, the International Crisis Group, an independent organization pursuing peace, noted that Abiy faced grave challenges from ethnic conflict: “Longstanding grievances among Ethiopia’s ethnic groups are becoming more acute. The forces that kept them at least partly in check are loosening, and all around the country groups that see each other as competitors are jostling for power.”

Almost as soon as Abiy assumed the reins of leadership he had to contend with a wide range of hostilities and frictions: intra-Oromo tension, tensions between the Oromo and ethnic Somalis and Amhara, tensions between the Amhara and Tigrayans and the TPLF.

Parts of the country have suffered a surge in ethnic violence, which has led to an estimated 2.2 million people displaced. In Jijiga and other parts of the Somali regional state, violence erupted on 4 August 2018, following attempts by the Ethiopian army to dismantle the ethnic Somali force, the Liyu police.

Protesters in the United Kingdom speak out against Abiy Ahmed Ali's administration, 2021.

Prior to the conflict in Tigray, tensions were simmering in the run up to the May 2020 elections, and Abiy was caught in the middle of these tensions on four fronts. First, Abiy had to contend with rivals and even some former allies in his home state of Oromia. His critics among his own people insisted he do more to advance the region’s interests politically. The Amhara were also at odds over Oromia’s desire for greater influence.

Third, Amhara politicians were in dispute with the TPLF over territories the Amhara claim Tigray annexed in the early 1990s. The fourth area of tension was between Abiy’s government and leaders of the TPLF. The latter perceived the prime minister’s reforms as a dismantling of a political system they had created and dominated, and this final tension escalated into the war currently embroiling the country.

Media Coverage of the Conflict

Accurate news about the conflict is hard to come by. Jeff Pearce, a Canadian journalist, maintains that the conflict in Tigray is a war on two fronts. One involves military and battlefields, and the other is a propaganda war against the Ethiopian government and Abiy’s actions in Tigray.

A destroyed armored vehicle on the streets of Hawzen in June 2021.

He contends that the Western media was “positively salivating over the prospect of war and expecting a nice, long one.” Additionally, the media have created an oppressor-versus-victim narrative. “You hardly, if ever, see a story in the mainstream news about the TPLF guerrillas themselves.”

The New Africa Institute, meanwhile, claims that large sections of the media have willingly accepted poor information and not shown patience to wait for credible evidence. Lawrence Freeman, a political and economic analyst who has conducted extensive research on Ethiopia, has complained that U.S. leaders are relying on dubious information rather than legitimate State Department or intelligence sources.

Disinformation and outright fake news have often won out. This media battle has only occasionally been directed towards an internal audience: the real targets were the Western news outlets, aid organizations, and Western policymakers.

Girma Berhanu, in an opinion piece written in May 2021 in Eurasia Review, notes that for many Ethiopians and foreign observers, the news coverage of the Tigray war embraced a decidedly anti-government point of view. “What every single media outlet failed to consider are the opponents in this terrible war. Variously described as rebels or as the elected government of Tigray region, their questionable track-record during their 30 years in power are never mentioned.”

He opines that the war in Tigray has garnered so much attention in the West simply because Abiy was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. “The story of a ‘Nobel Peace Prize laureate’ waging war is simply too good to refuse. Who cares about wars in other parts of Africa? They are too messy and convoluted. Mr. Saint turning out to be a Dr. Devil is a far juicier story.”

Epilogue

As the war continues, hostilities have spread into the neighboring Afar region, east of Tigray. Tigrayan fighters have advanced south and southwest, taking control of several towns in the area of Woldiya and Gondar.

A man passes by a destroyed tank in Edaga Hamus, a town in the Tigray region, June 2021.

The objective of the TPLF is to force Ethiopian leaders to agree to their terms of a ceasefire. According to Getachew Reda, spokesperson for the TPLF, the Front is demanding a transitional arrangement that will address their grievances.

Essentially, they are calling for the ouster of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. They have characterized Abiy as a perpetrator of genocide in the region. The Prime Minister on the other hand has labelled the TPLF as a terrorist organization intent on secession.

Whatever the outcome, it is increasingly clear that there is enough blame to go around. The victims, however, are the Ethiopian people.

Academic Books:

Bahru Zedwe. A History of Modern Ethiopia 1855–1991. Suffolk: James Currey. 1991.

Richard, Pankhurst. The Ethiopians. Oxford, UK Blackwell Publishers. 1998.

United Nations, Human Rights, and Amnesty International Reports:

Tigray aid situation worsening by the day, warn UN Humanitarians,” United Nations News: Global Perspective Human Stories (Sept. 2, 2021) https://news.un.org/en/story/

United Nations News: Global Perspective - Sept. 2, 2021

“Ethiopia: Tepid international response to Tigray conflict fuels horrific violations over past six months.” Amnesty International Report May 4, 2021

Alex De Waal, Evil Days: 30 years of War and Famine in Ethiopia, Human Rights Report, 1991.

News Articles, Opinion Pieces, and Blogs

Yohannes Woldemariam, “The Unenviable Situation of Tigreans in Ethiopia, Africa at LSE Blog https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2018/03/28/the-unenviable-situation-of-tigreans-in-ethiopia/

Aregawi Berhe, “The Origins of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front,” African Affairs, Oct. 2004 vol.103, no. 413.

John Young, “Ethnicity and Power in Ethiopia.” Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 23, No. 70(Dec, 1996) pp. 531-542.

Kevin Hamilton, “Beyond the Border War: The Ethio-Eritrean Conflict and International Mediation Efforts,” Journal of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University Press, July 2000.

Yohannes Gedamu, opinion Dec. 18, 2019 “Why Abiy Ahmed’s Prosperity Party is good news for Ethiopia.” Al Jazeera, Opinion, Dec. 18, 2019.

The International Crisis Group Reports on Ethiopia, Sept. 2018- Present

Jeff Pearce- Blog: Ethiopia: “The Bogeyman Gets Smaller,” May 26, 2021 (https://jeffpearce.medium.com/ethiopia-the-bogeyman-gets-smaller-501a51e3fe9a)

New Africa Institute, https://www.newafricainstitute.org/ (May 2021)

Lawrence Freeman “Incestuous Relationship Between Western Politics and Western Media: Case of Ethiopian Conflict-Op-ed,” Eurasia Review, News and Analysis, July 6th, 2021.

Getachew Reda, TPLF Spokesperson- Twitter Sept. 18, 2021 Twitter. https://twitter.com/reda_getachew/status/1439295084206362625?lang=en.

Abiy Ahmed’s book:

Abiy Ahmed, Medemer, Teshai Publications, Ethiopia, 2019.