The Arab-Israeli War of June 5-10, 1967 (known in the West as the Six Day War) was a brief but momentous military clash that reshaped the Arab-Israeli dispute, redirected U.S. relations with key states of the Middle East, and resulted in territorial and political changes that remain consequential on this month’s 50th anniversary of the war.

Israeli and Egyptian forces clashing during the Six Day War, 1967.

The 1967 armed contest was the third in a series of Arab-Israeli international wars. It was preceded by a conflict in 1948-49 in which Israel secured its independence by defeating invading armies from Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq and suppressing internal resistance from indigenous Palestinian Arabs; and by an unsuccessful 1956 gambit by Israel, in collusion with Britain and France, to secure its southeastern border by invading Egypt and causing the downfall of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

While diplomats of the United States and other members of the United Nations (U.N.) arranged ceasefires in 1949 and 1956, they failed to resolve the complex underlying Arab-Israeli controversies over territorial boundaries and sovereignty, the status of Jerusalem, the disposition of Palestinian refugees who had been uprooted by the 1940s warfare, control of the precious fresh water of the Jordan River, international trade, and other political and economic issues.

Festering disputes over these issues set the stage for the 1967 war.

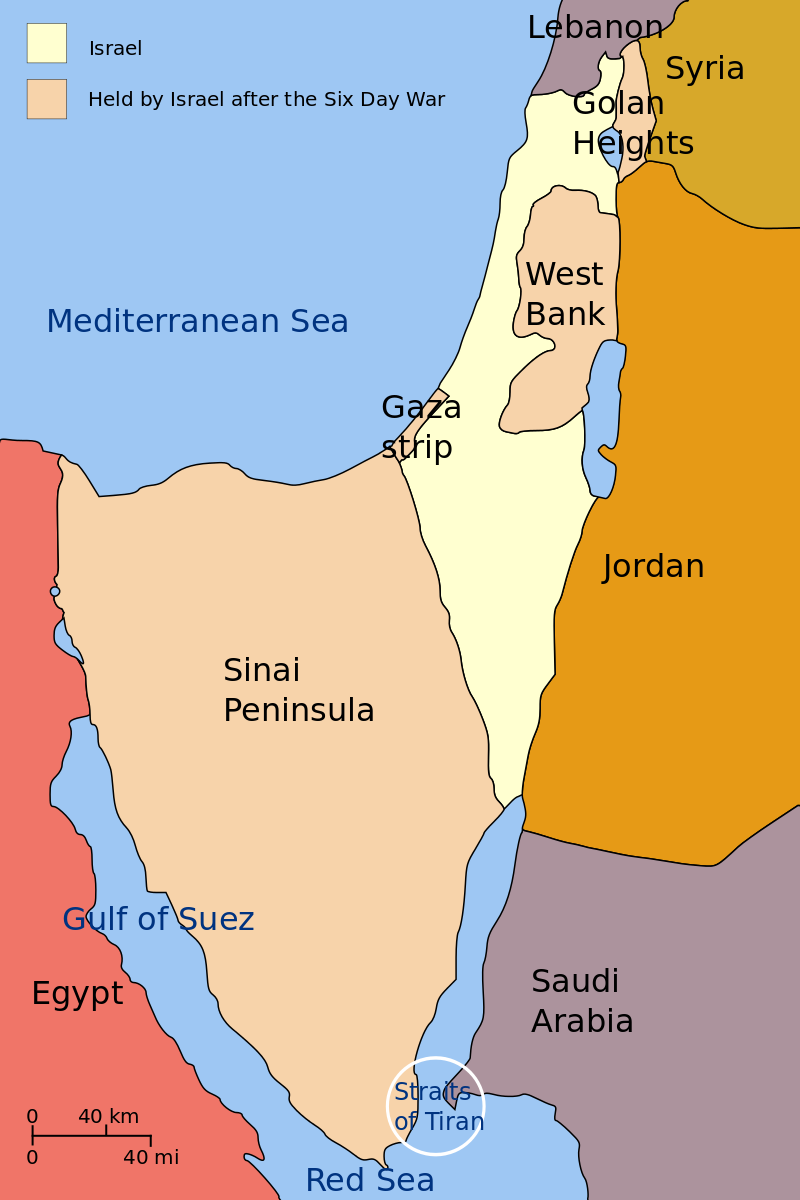

Map of Israeli borders before and after the Six Day War of 1967.

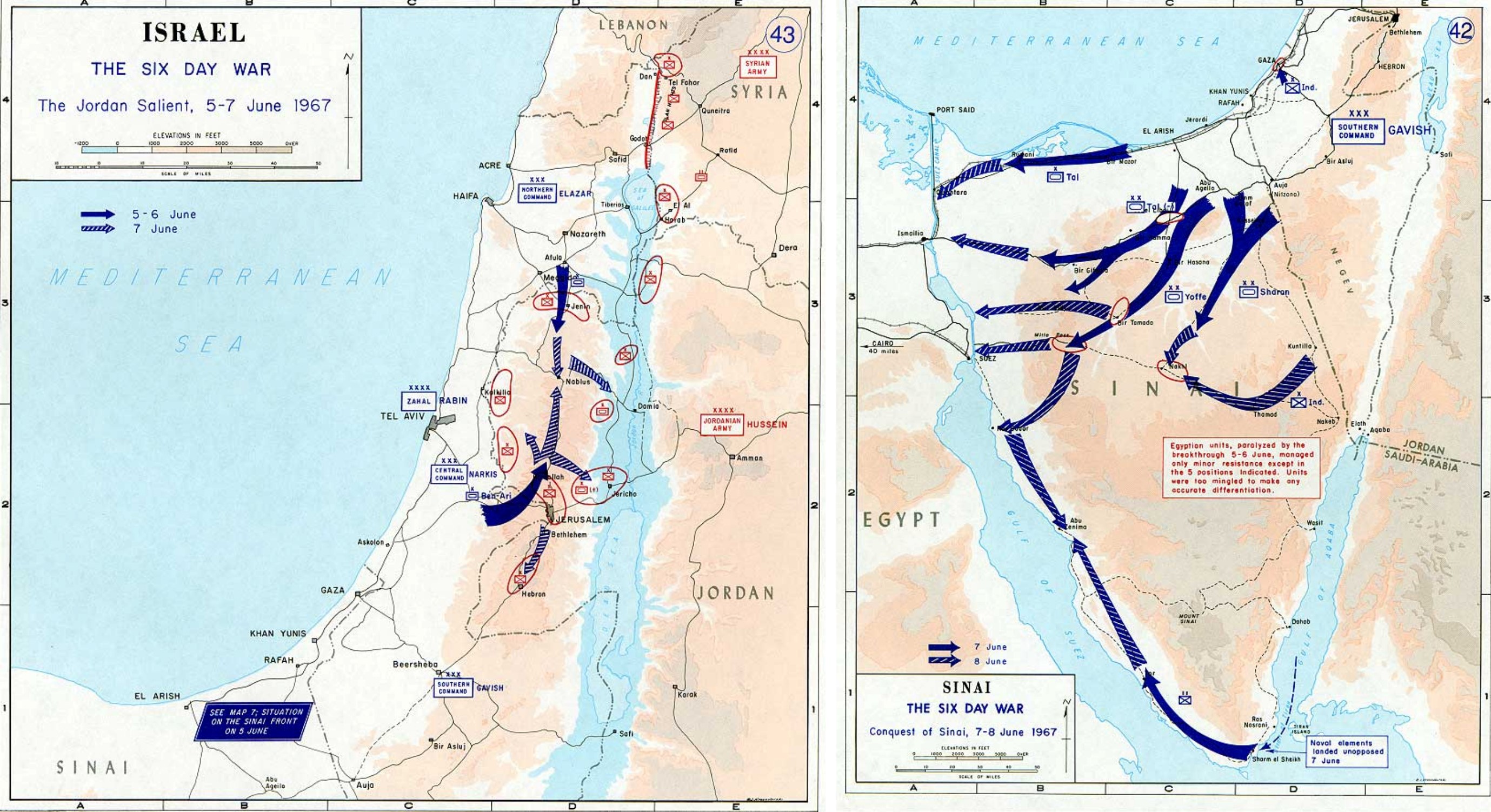

Tensions along the Israeli-Syrian border led to dogfights in early April in which Israeli military jets downed Syrian aircraft, and to violence in northern Israel that prompted Israeli threats to occupy Damascus in early May. President Nasser of Egypt ordered U.N. peacekeeping forces that had been embedded in the Sinai Peninsula since the 1956 ceasefire to evacuate that territory. Egyptian troops occupied the U.N. military bases and closed the Straits if Tiran to Israeli shipping, threatening to choke trade routes vital to Israel. The leaders of Israel threatened to use force to reopen the waterway and otherwise deal with Egyptian threats. On June 5, they made good on such threats by preemptive military action aimed initially at Egypt.

U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson attempted to resolve the mounting crisis by appealing to Nasser to rescind his moves against Israel, by cautioning Israel to rely on peaceful means to ensure its interests, and by organizing a multilateral Western initiative to break the Egyptian blockade through assertive means including naval force. These maneuvers faced numerous political and tactical obstacles, however, and they failed to dissuade Nasser from his confrontational approach or to deter Israel from escalating the hostilities.

The Lyndon B. Johnson White House situation room during the Six Day War.

Scholars have debated whether Johnson, in the days preceding hostilities, continued to discourage or perhaps even secretly authorized the Israelis to take offensive action. Memoirs by Israeli officials and snippets of archival evidence make it plausible that the president, frustrated by Nasser’s policies and calculating U.S. domestic political factors, diminished his opposition to Israeli military action.

Yet other archival evidence indicates that numerous U.S. diplomats in the Middle East continued to counsel peace on all states, consistent with policy directives sent by the State Department, and that Johnson privately expressed regret about the war’s outbreak and expected repercussions.

This debate among scholars might be resolved in part by recognizing that officials in the multi-layered U.S. government communicated a range of messages including some statements that were construed by Israeli leaders, who faced profound security threats, as encouragement to take up arms.

On June 5, 1967, Israel launched a series of military attacks beginning with a surprise aerial assault that demolished Egyptian airpower. In succeeding days, the Israeli military inflicted decisive military defeats not only on Egypt but also on Jordan and Syria.

Israeli troops examine destroyed Egyptian aircraft, June 1967.

By the time the U.N. brokered a ceasefire on June 10—after six days of combat—the Israeli military occupied vast swaths of Arab territory including the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula (taken from Egypt), the West Bank (from Jordan), and the Golan Heights (from Syria). Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, including many who had fled to those territories as refugees in the 1940s, were uprooted and forced to flee across the international borders of historic Palestine.

Map of Israeli movement into the Jordan salient June 5-7 (left) and the Sinai Peninsula, June 7-8 (right).

Whatever the consistency of U.S. opposition to the outbreak of war, the Johnson administration moved quickly to end the fighting and contain the resulting instability.

U.S. officials secured the U.N. Security Council ceasefire resolution and pressured the belligerents to accept it. Johnson sought to prevent Soviet political gains by pressuring Moscow to accept U.S. ceasefire terms and by moving U.S. naval ships into the Eastern Mediterranean after the Soviets threatened vaguely to intervene militarily on behalf of the Arab states. In late June, the U.S. president met Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin in an impromptu summit meeting in Glassboro, New Jersey in an effort to de-escalate superpower tensions that had been aggravated by the war.

The June 1967 war dramatically recast the political dynamics of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Israelis became euphoric that they had survived the seemingly-mortal threats arrayed against them, scored a huge victory, and captured land that they could use as bargaining chips to shape Arab behavior.

Arab leaders were devastated by their catastrophic defeat, and made false charges that U.S. military forces assisted the Israeli assault on Egypt. The war would prove to be a watershed in Arab politics by discrediting secular nationalist leaders such as Nasser and thus contributing to the rise of radical and religious ideologies and leaders.

These consequences perpetuated the territorial outcome of the 1967 war and hindered diplomatic initiatives to promote a permanent peace settlement. Bitter anger among Arab leaders and an attitude of superiority among Israeli leaders created poor conditions for postwar peacemaking.

In November 1967, the Johnson administration achieved passage of U.N. Security Council Resolution 242, which called for a peace settlement including Israeli withdrawal from territories occupied in June and Arab recognition of Israel’s right to exist as a state.

That resolution, however, included two crucial ambiguities. First, it provided that Israel would withdraw from “territories” rather than “the territories,” a loophole that gave Israel legal footing to claim permanent retention of some of the land it had occupied. Second, the resolution failed to specify whether Israeli withdrawal should precede or follow Arab recognition. These ambiguities strictly limited the eventual effectiveness of U.N. 242 as a basis for permanent peace agreements.

Meeting of the United Nations Security Council on June 7, 1967. (UN photo by Teddy Chen)

The 1967 war also strained U.S. relations with the belligerent states. Although U.S. officials rejected the accusations by various Arab leaders that U.S. warplanes had participated in the Israeli attacks against them, anti-U.S. passions soared in Arab countries. Mobs threatened the safety of U.S. nationals, and Arab governments severed diplomatic relations with the United States.

U.S.-Israeli relations experienced temporary strain during the war after Israeli warplanes attacked the U.S.S. Liberty, a naval intelligence-gathering ship sailing off the coast of Egypt, killing 34 U.S. sailors, on June 8. Israeli resistance to postwar diplomacy to achieve permanent peace agreements also irritated U.S. officials.

Offsetting these U.S.-Israeli tensions, however, Israel enjoyed surging support in U.S. public opinion and in subsequent years, U.S. officials came to identify it as the most stable and reliable state of the region.

The 1967 war has cast a prominent shadow over fifty years of Middle East history. The scale of Israel’s battlefield victories burnished its enduring reputation as the region’s foremost military power. From such a position of strength, Israel used the prospective return of the occupied territories as levers in peace negotiations with Arab states, with a range of results.

On one hand, Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula in exchange for diplomatic recognition by Egypt under the Egypt-Israel peace treaty of 1979, the first-ever Arab-Israeli settlement. On the other hand, Israel remained in the Golan Heights amidst perpetual deadlocks in Israeli-Syrian peace talks and persistent border tensions. In fact, Israel announced the formal annexation of the Golan in 1981 (a move not recognized by the United States and most other countries) and in subsequent years promoted the settlement of thousands of Israeli citizens on the disputed territory as a way of solidifying its Israeli character.

Israel’s control of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip remain highly contentious in 2017. Jordan (which in 1994 became the second Arab state to sign a peace treaty with Israel) and Egypt relinquished their respective claims over the West Bank and Gaza to the Palestinian inhabitants of the territories.

Yasser Arafat, who rose to prominence in the 1960s by organizing violent resistance to Israel among the stateless Palestinians, began exhibiting statesmanlike behavior during a late 1980s Palestinian uprising known as the intifada. That transition, as well as such global dynamics as the end of the Cold War in 1989-91 and the Gulf War of 1990-91, set the stage for the U.S.-brokered, Israeli-Palestinian peace process of the 1990s.

Palestinians during the first intifada, 1987. (Photo by Peter Stepan)

Based on the “land for peace” formula of U.N. Resolution 242 of 1967, the peace process brought Israel and the Palestinian community to the verge of a treaty that would establish a Palestinian state in portions of the West Bank and Gaza, a state that was committed to recognition of and peaceful coexistence with Israel.

By 2000, however, the peace process collapsed short of a final settlement over irreconcilable differences between the two camps on such matters as the actual borders between Israel and Palestine, the property rights of Palestinian refugees, and the prospect that Jerusalem could serve as the capital city of both countries.

The deadlock of the peace process helped spark a second, more violent intifada by Palestinians in the occupied territories, which Israel suppressed with severe security measures. Falling increasingly under the sway of their citizens who opposed yielding the West Bank, Israeli officials took two steps to make permanent their control of that territory.

First, they promoted massive construction of settlements, housing hundreds of thousands of Israeli citizens, in West Bank locations with strategic, cultural, and political significance. Second, they erected a concrete and barbed-wire wall to shield the settlements (as well as Israel proper) from violence or rebellion—in the process disrupting the mobility of peaceful Palestinians as well. Both measures had the subtle effect of solidifying the Israeli identity over and attachment to substantial portions of the West Bank, making it tactically more difficult to effect a land-for-peace deal.

Ma'ale Adumim Israeli settlement in the West Bank.

In Gaza, Israeli officials faced acute violence perpetrated by religiously-inspired Hamas militias. In 2005, Israel withdrew its settlers and occupying forces from Gaza, although on several occasions thereafter it intervened militarily in Gaza to suppress Hamas and eliminate its leaders.

Fifty years on, the June 1967 Arab-Israeli War continues to reverberate across the Middle East: in Israel’s military superiority to its Arab neighbors and its expansive territorial aspirations in the West Bank and Golan; in the political instability of several Arab states and their strained relationships with the United States; and in the statelessness and resultant deprivations of the Palestinian people.