The Crimea that most people have come to know is a peninsula occupied by Russian forces, ostensibly annexed to the Russian Federation, and one epicenter of an international conflict over Ukraine that seems far from resolution.

While we look to history for answers and explanations of these current events, this place has a tremendous story to tell in its own right. Here are ten fascinating moments from this remarkable center of contact and conflict in world history.

(But First ) From the Steppe to the Sea: A Geographical Overview

A peninsula jutting into the Black Sea, most of Crimea is steppe (prairie, often cool and dry), including all of its northern regions, Simferopol, the northern environs of Sevastopol in the west and Feodosia in the east. The Crimean Mountains, which slope right into the sea, create a second warmer and sunnier climate zone along the south coast of the Black Sea, where lush tourist resorts such as Yalta are located.

1. Crimean Antiquity

Settlements first appeared in Crimea in the 9th to 6th centuries BCE, particularly towards the coastline’s mountain slopes. Herodotus, ancient Greece’s original historian, called Crimea’s local peoples the Tauri when he came to the region to visit Greek colonies. Greeks had settled at the magnificent Chersonesus, now just east of Sevastopol, among other places According to Herodotus, the Greeks and Tauris fought relentlessly and he went so far as to call their Tauri foes marauding pirates. Crimea’s classical name, used often until the twentieth century, was Taurica (Tavrida in Russian).

2. The Emergence of the Crimean Tatars

Beginning in the thirteenth century, Italian merchants (from the city-state of Genoa) took control of trade along the south coast of Crimea for two hundred years. Crimean Tatars, a Turkic-language speaking peoples who inhabited the steppe north of the coast, combined forces with the Ottoman Empire and expelled the Genoese merchants from Caffa, their largest trading port (now Feodosia). Caffa became infamous during a siege in 1347 when, Mongols hurled corpses infected with the plague over city walls—one of the first recorded cases of biological warfare in human history. Infected traders and residents likely spread the famous Black Death to Europe. Partly independent and partly subject to the Ottoman Empire, the Crimean Khanate existed from 1441-1783.

3. Russia Annexes Crimea

Beginning in the 1760s, under the guidance of Empress Catherine the Great, plans were laid for an invasion of the peninsula with the goal of subordinating the “barbarous and savage” Crimean Tatars. After a series of wars from 1768-74, which resulted in Russian victory and the expulsion of Ottoman influence, Catherine ordered the creation of a Crimean state, independent from Russia. In 1783, after the Tatar ruler she imposed proved unpopular and with no one powerful enough to stop her, she announced the formal annexation of Crimea into her empire.

4. Catherine’s Grand Tour

In 1787, Empress Catherine the Great set out on a Grand Tour of the lands her forces conquered in the south. Her “favorite” (and lover) Grigorii Potemkin prepared extensively for this visit, to the point where “Potemkin Villages—facades set up to impress the Empress—became the stuff of legend (though it is likely that Potemkin Villages were actually just that: legends propagated as part of court intrigue). The most crucial feature of Catherine’s Crimean tour was how it symbolized the importance of Crimea to Russia, as the ancient site where, according to medieval Russian documents, Prince Vladimir “the Baptist” founded the Russian Orthodox Church in 988 CE.

5. The Crimean War (1853-56)

In 1853, Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire, ostensibly over the mistreatment of Slavs and Orthodox Christians who lived under Ottoman rule. Britain, France, and Sardinia responded by successfully invading Crimea, fearing Russian control of the straits connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Military debacles and disease plagued both Russia and the invading allies. Often evoked in Russia through Tolstoy’sSevastopol’ Sketches, the war is best remembered in the West for the tragic heroism of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem Charge of the Light Brigade and for Florence Nightingale, who founded the modern nursing profession while serving British soldiers.

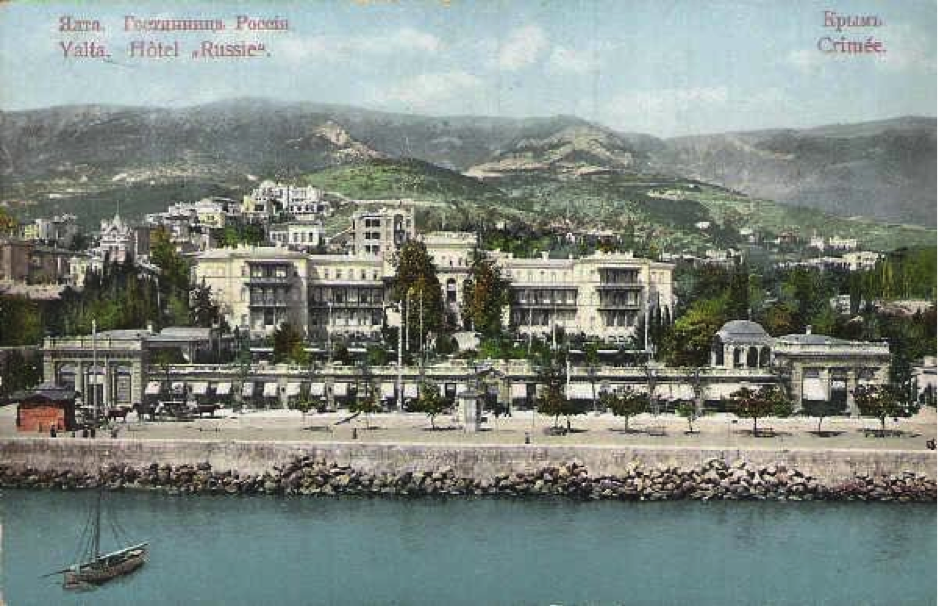

6. The Russian Riviera

Crimea became the destination of some of Russia’s first tourists in the early nineteenth century. Tsars Alexander II, Alexander III, and Nicholas II visited Crimea’s Black Sea coast annually for decades after the Crimean War. Wealthy aristocrats followed them, purchasing land and building magnificent villas across the mountainous landscape. By 1900, Crimea earned the moniker “the Russian Riviera:” the most fashionable tourist location in the empire and a “coast of health” that Russians suffering from tuberculosis and other ailments went to receive treatment. Crimea enticed hundreds of thousands of Russians to visit or permanently relocate there in the years leading up to the First World War.

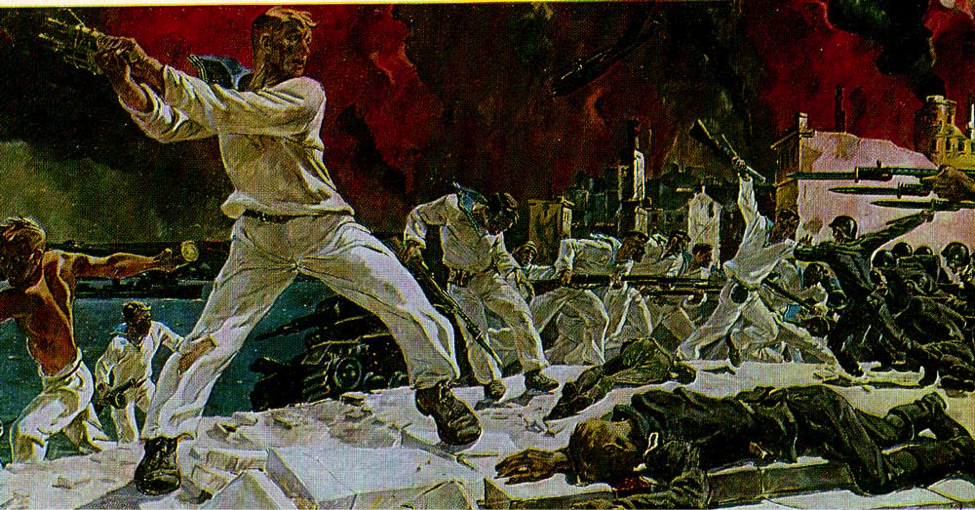

7. Sevastopol: Hero-city

German aircraft during World War II besieged Sevastopol for 250 days from October 1941 to July 1942. Defended by navy units, Sevastopol became the location for a full-scale Soviet push-back against Nazi forces. Despite the efforts of thousands of Soviet factory workers, medical personnel, and soldiers, a Nazi bombardment that destroyed much of the city’s infrastructure in June 1942 proved decisive. Soviet troops withdrew, but returned in 1944 to liberate the city. 50,000 men and women were awarded a special medal “For the Defense of Sevastopol” and the city itself was given the prestigious title of “Hero-city.”

8. The Deportation of the Tatars

When the Red Army recaptured Crimea in 1944, the entire Crimean Tatar community was unjustly accused of collaborating with the Nazis. Thousands of NKVD agents (Stalin’s secret police, precursor to the KGB) in mechanized infantry units moved into Crimea on May 18, 1944, surrounding virtually every Tatar village. With one hour to collect their belongings, the NKVD transported Tatar communities at gunpoint to train stations, and loaded them into cattle cars modified only with a small pipe for defecating in the corner. The entire community was deported, mainly to Uzbekistan, and because many of the trains were sealed, and the victims given virtually no food, thousands died during the voyage.

9. Crimea and Ukraine

In 1954, to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Russia’s union with Ukraine, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev transferred Crimea to a different administrative division of the USSR, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. This shift in borders within the USSR was of little consequence at the time. However, when Ukraine emerged as independent state in 1991, the interested parties came to the following agreement to prevent a crisis in the predominantly Russian Crimea: Crimea remained a province of independent Ukraine but Russia kept their naval forces in Sevastopol (on a contractual lease) and the Crimeans received autonomy and recognition of their special historical status inside Ukraine.

10. The Santa Barbara Affair

Since the late nineteenth century, Crimea’s predominant language has been Russian, and Crimea’s Russians have cared deeply about their right to speak their native language even as part of Ukraine. In the early 1990s a crisis emerged when the Ukrainian government broadcast a popular American soap opera, Santa Barbara (which ran from 1984-93 and was dubbed into Russian) in Ukrainian. Many Russians—viewing the Ukrainian language as nationalist imposition of the Ukrainian government, a peasant language, and as inferior to Russian—marched to the Parliament and demanded a reversal of the policy, calling it linguistic imperialism.