On May 12, 1949, the Soviet Union officially lifted its blockade of West Berlin, allowing trains, barges, and passenger transit from Western-Occupied Germany to legally enter West Berlin for the first time since June 24, 1948.

The blockade, one of the earliest episodes in the Cold War, was largely ineffective because of several factors, including the porous nature of Soviet occupation, West Berliners’ resistance to Soviet aid, and the efficacy of the Berlin Airlift. Also, the Soviet Union simply did not have the means to support their German holdings without supplies and material from the West. These factors ultimately led the Soviets to the negotiating table.

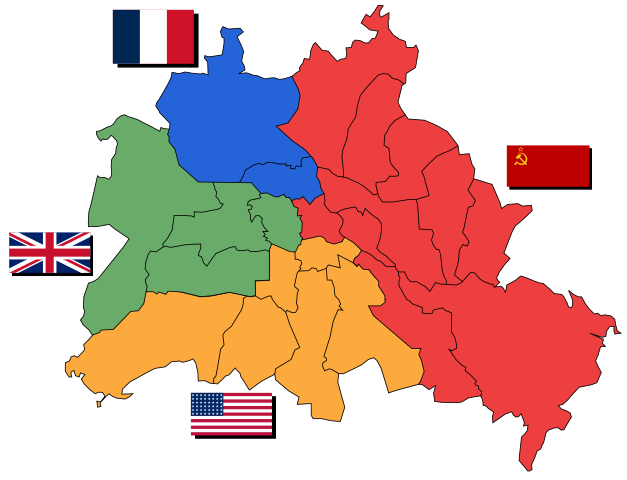

The Soviets instituted the Berlin Blockade in response to the decision by the USA, Great Britain, and France to replace the stagnant German currency, the Reichsmark with a new one, the Deutsche Mark. The Soviets opposed the currency reform, but the reform represented more than simple Monetary disagreements.

The Soviet government believed that control of Germany was crucial to establishing and expanding their hold over Eastern Europe, and a Western-backed currency directly opposed that vision, as did the existence of a hub of Western democracy in the heart of East Germany.

To achieve their goal of control, the Soviets planned to use the Blockade to turn West Berliners against the Western powers by making them reliant on Soviet goods and services, and by cutting off any contact with the West.

The Berlin Blockade began officially in June, 1948, but several loopholes and oversights by the Soviets allowed for a steady supply of goods into the city until the Soviets enacted stricter regulations and crackdowns. Despite these crackdowns, very few chose to accept Soviet offers for food aid.

The Soviets offered ration cards for Soviet foodstuffs and fuel, yet in the first two weeks of the program, only 21,000 West Berliners filed for a card, less than 1% of the total population of West Berlin. In fact, at its height in March 1949, only 103,000 Germans had signed up for Soviet ration cards, equal to about 5% of the total population.

West Berliners declined the Soviet ration cards for a variety of reasons. Initially, many believed that the Soviet Union would simply be unable to deliver on its promise, while others were able to stay well supplied because of holes in the blockade. Others cited ideological reasons, choosing to side with the West out of principle or because of the efficacy of the Berlin Airlift in winning their support. Regardless of the reasoning, it is evident that most West Berliners relied either entirely or mostly on the Berlin Airlift to survive.

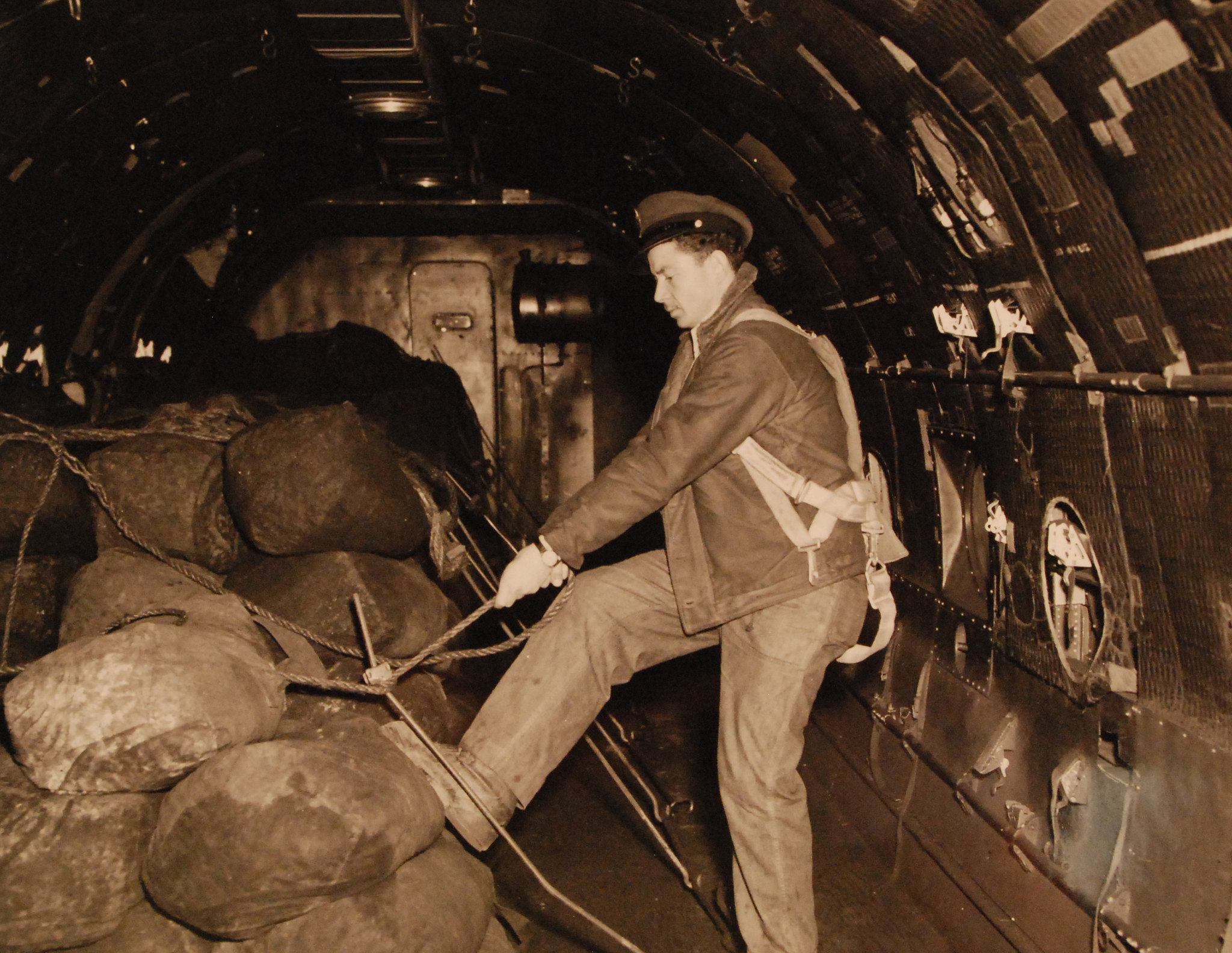

The Berlin Airlift began on June 26, only two days after the Blockade when the US government initiated “Operation Vittles,” the plan to airlift supplies to West Berlin using the U.S. Airforce in Europe. The British government, working in tandem with the United States, began “Operation Plainfare,” on June 28.

To achieve their goals, the British and U.S. planes launched several times every day, and at the zenith of the airlift, one plane loaded with supplies landed in Berlin every 45 seconds. The Western powers met their goal of dropping 3,475 tons of goods per day, and by its peak in 1949, they were delivering 12,491 tons per day.

This was no easy task. The Western powers constructed new runways in both major West Berlin airports just to accommodate the increased traffic from the large, heavy, Western bombers and supply planes. By the end of the airlift, they had flown over Berlin more than 250,000 times delivering 2,334,374 tons total.

Especially popular amongst children because of the sweets they delivered, the planes, dubbed “raisin bombers,” also succeeded in winning the hearts and minds of West Berliners.

Embarrassed by the success of the Berlin Airlift, and facing the realization that their supplies were inadequate to continue feeding West Berlin, the Soviet leadership elected to end the blockade and resume free travel between West Berlin and Western-occupied Germany.

Despite this, planes continued to deliver supplies until September 1949 to build an adequate stockpile in case the Soviet Union decided to resume the blockade. The Soviets never implemented this tactic again, but the events that led to the blockade, and the Western efforts during the blockade, contributed to increased tensions and the eventual construction of the Berlin Wall.

In addition to its impact on East-West relations in Germany, the Berlin Airlift also offers a reminder of the stark difficulty of humanitarian operations conducted even in fairly accessible locations. To feed the city took the coordinated efforts of two Great Powers following the war, and cost millions of dollars. In places like Gaza and Ukraine in 2023-2024, the West faces comparatively more dangerous and difficult situations.

Though the Berlin Airlift was no doubt a success, it should be viewed as an exception rather than the standard by which to compare modern humanitarianism. It illustrates both the triumphs of Western humanitarians and the tremendous efforts it takes to achieve such victories even in mostly ideal conditions.

![]()

Further Reading:

To Save a City: The Berlin Airlift, 1948-1949

Berlin on the Brink: The Blockade, the Airlift, and the Early Cold War

"The Incomplete Blockade: Soviet Zone Supply of West Berlin, 1948–49"