On the surface, HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 seem as dissimilar as two viruses could possibly be. Yet, the ways in which the Soviet Union reacted to the arrival of HIV/AIDS, and how it spread in the first years of the outbreak, yield valuable insights into our current coronavirus pandemic.

In particular, the Soviet Union’s approach to HIV/AIDS in the late 1980s—how officials initially blamed foreign nations for the virus and denied the possibility of extensive community spread among the Soviet population—offers a cautionary tale worth considering as the United States struggles to cope with COVID-19.

Soviet scientists and medical experts began tracking the virus in 1985 at the Ivanovsky Institute of Virology in Moscow. From the start Soviet officials pushed forward the idea that it was a foreign virus. By the end of 1987, there were fifteen known cases of HIV/AIDS in the USSR. By 1990, that official number had grown to around 565.

An AIDS testing site in Moscow, 1987.

The number of infected was initially low in comparison to the USA, where the virus was spreading more rapidly. Soviet virologists were also quick to add that of the 565 infected, around 70-80% were foreign nationals and not Soviet citizens at all. These statistics have been disputed, and experts now believe that the number of infected was actually much higher in the late 1980s Soviet Union.

The Ministry of Health, the USSR’s all-encompassing health and wellness institution, also stated that HIV/AIDS was a virus of licentiousness and lax morality. They often stated that foreigners, especially from the West, had looser standards of sexuality. They believed that Soviet youth were less likely to catch and spread the virus in a “casual” manner and were far less likely to engage in sexual activity with foreigners.

Notably, Yevgeniy Chazov, the Minister of Health and a prominent cardiologist, stated in 1988 that, “The actions of the entire population to comply with moral and ethical standards of behavior are the first and main guarantee against [new] AIDS infections.” Thus, initial concern focused mostly around foreigners entering Soviet borders and with Soviet citizens’ interactions with those foreigners.

Dr. Yevgeniy Chazov, Minister of Health of the USSR from February 1987 through March 1990.

The popular response to HIV/AIDS of the press and concerned citizens writing to the Ministry of Health mirrored that of the official response in casting blame on foreigners. When Soviets did turn their attention to their fellow citizens, they took aim at “at-risk groups,” including intravenous drug users, sex workers, and homosexual and bisexual men.

Letter writers to Soviet newspapers floated the idea of setting up a colony for the infected, akin to a leper colony. After all, the Soviet Union was not unfamiliar with mass re-location of “troublesome” individuals to its Far East regions.

At the same time, many young people were remarkably unconcerned about the virus. Like in the USA, the notion spread that only homosexual men were prone to infection through sexual contact. Specific to the USSR, many young Soviet women boldly stated that they were not concerned about infection because they did not have sex with foreign men.

Abstention of sexual relations with foreigners was long seen as the patriotic thing for Soviet women to do. In the 1980s, the Soviet state attempted to combat an explosion of foreign-currency prostitution, as border control relaxed during the Gorbachev years. It also warned women against getting involved with foreign men, as the 1980 Summer Olympics, held in the USSR, had resulted in a baby boom of children fathered by foreign athletes and spectators.

A cartoon from Pravda, the daily paper of the CPSU Central Committee, claiming that AIDS was manufactured in the Pentagon, 1986.

While the official state response to the virus was to downplay the threat and extent of HIV/AIDS, the state privately ramped up surveillance efforts against foreigners and Soviet citizens within “at-risk” groups. The Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), the Soviet internal security police, drafted several reports tracking drug users, sex workers, and homosexual and bisexual men.

Even more than before, these “at-risk” populations were seen as posing a threat to the security of the Soviet state. The MVD’s surveillance of these communities of people, while the press cast blame on them, worked to dissuade “at-risk” individuals from seeking testing and treatment, spurring the spread of the virus.

The negative attention given to homosexual men may also have been partially responsible for why the criminal statute against homosexuality in the USSR, Statute 121, was not abolished from the criminal code during an otherwise unprecedented time of reform (perestroika).

In 1990, the Ministry of Health released a report titled, “Mathematical modeling and forecasting the development of the AIDS epidemic in the USA and the USSR.” The report estimated that roughly 2 million Americans were infected with HIV/AIDS in 1988, while only 102 people were infected in the USSR. It further projected that by the year 2000, 54.8 million Americans would be infected with HIV/AIDS while approximately 55.6 thousand would be infected in the Soviet Union.

These figures proved wildly wrong. In 2016, the USA reported 1.1 million cases and post-Soviet Russia, with half the population, had 1.5 million cases.

The 1990 report was shaped by the same erroneous assumptions that guided the Soviet response to HIV/AIDS in the first place. The authors reasoned that the USA had a much higher population of “at-risk” individuals, around 5-8%, while the USSR’s population of “at-risk” individuals was around 2-3%.

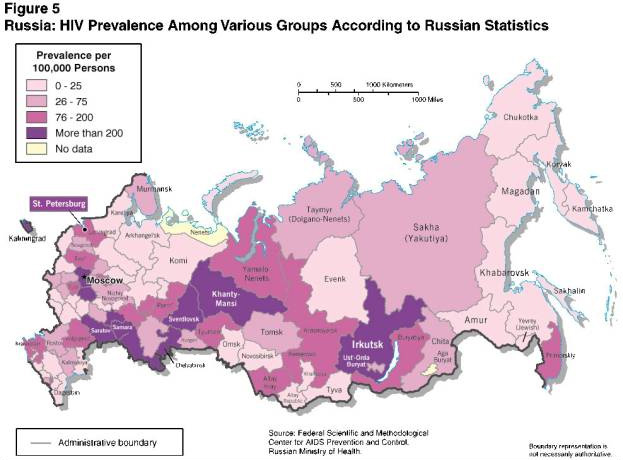

A map of HIV infections in Russia, 2002 .

The Soviet experts were right about who the virus would target in Russia: IV drug users, sex workers, and homosexual and bisexual men. However, for political reasons, they greatly underestimated how many people fell into these “at-risk” groups.

The rise of the HIV/AIDS epidemic presented a dilemma for Soviet leadership. It coincided with expansive reforms to “open up” the Soviet Union to the rest of the world. The threat of the virus spurred Soviet experts to work more closely with international research and relief organizations, especially the World Health Organization (WHO). This partnership coincided with the end of the Cold War and helped to assert the USSR’s place on the world stage as collaborative and humanistic.

At the same time, by blaming foreigners for HIV/AIDS, Soviet leaders promoted the idea that the USSR should remain a closed society and undermined its own steps in global pandemic response.

Russian postage stamp created to memorialize victims of HIV/AIDS, 1993.

And labeling HIV/AIDS as a virus of “lax morality” created stigma around those infected, especially for homosexual men who feared a positive diagnosis was an admission of a crime. Many infected persons avoided diagnosis and treatment for the first several years of the epidemic in the USSR, allowing the virus to spread rapidly and widely.

There are some obvious parallels between the response to HIV/AIDS in the Soviet Union and actions taken by the United States government (and many others, such as Brazil) during the COVID-19 pandemic. At first, both governments denied that the virus posed a real threat to their respective nations. Trump administration figures continue to downplay the extent of COVID-19 infections and deaths.

Both governments also resorted to anti-foreign rhetoric and policies. The Trump administration has repeatedly called COVID-19 “the Chinese virus” in an attempt to deflect blame for the outbreak and among its first actions was a series of travel bans.

Finally, the US administration has been reluctant to participate in international efforts to combat the virus and has repeatedly attacked the WHO. The USSR, even while suspicious of foreigners and international health organizations, engaged in robust collaboration with the WHO during the first years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

But one lesson from the Soviet experience with HIV/AIDS is clear. The strategies of blame and dishonesty employed in the 1980s failed and led to far more suffering than would have been the case had Soviet officials confronted that virus honestly and directly.