In recent weeks, the Yellow Vests (Gilets Jaunes) protest movement has convulsed France. As high emotion and violence grip the country, we are reminded that France is no stranger to political protest. The country has a long history of its people taking to the streets to show their discontent with the status quo.

While originally peaceful, some protests by the Yellow Vest movement—Gilets Jaunes—in France have turned violent in recent weeks.

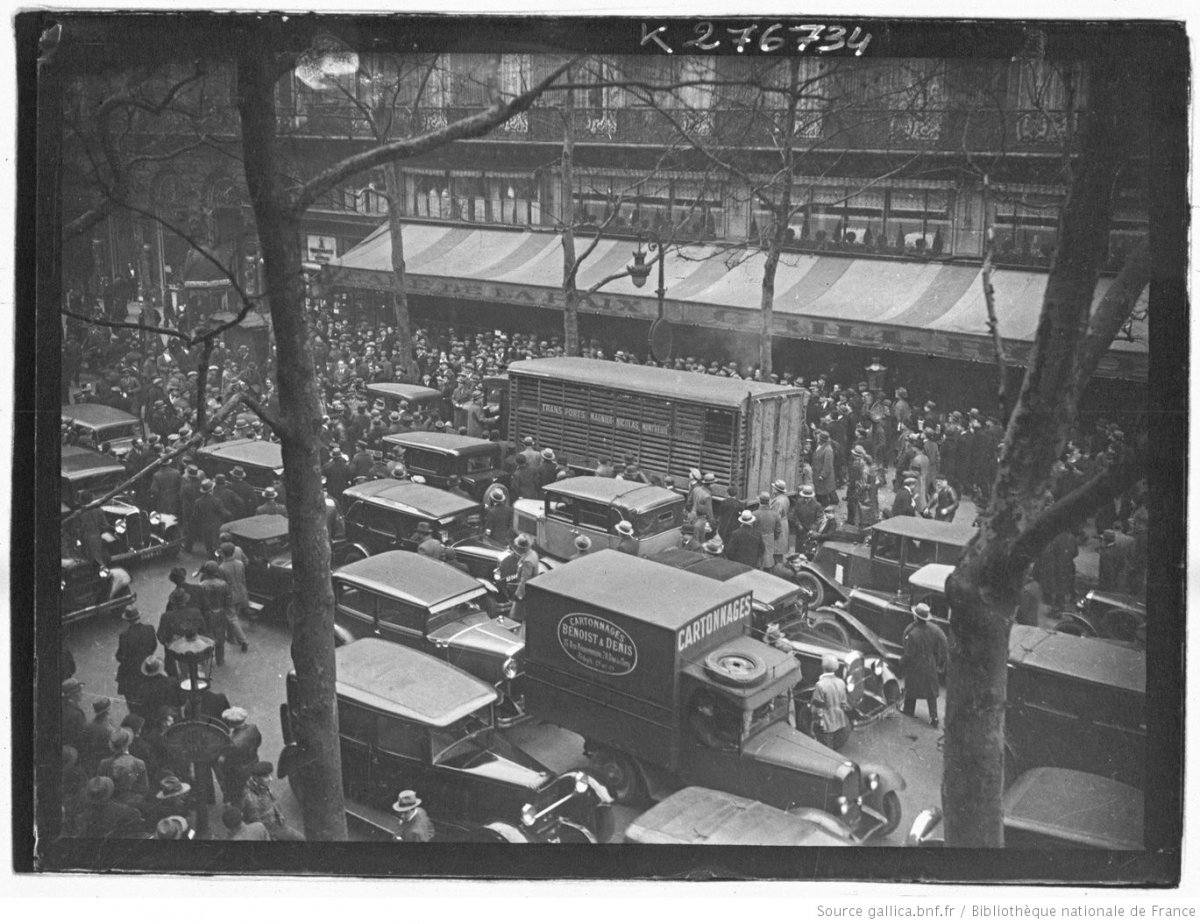

On February 6, 1934—85 years ago—tens of thousands of demonstrators amassed in the streets of Paris to protest the center-left government. Gathering at the Place de la Concorde, the disorganized, and largely far-right, crowd erupted into violence as night fell. The protestors burned buses and destroyed property as they attempted to breach the barriers surrounding the Chamber of Deputies where the parliamentary deputies were in active session.

Police, panicking at the intensity of the protest-turned-riot, fired into the crowd, and a battle ensued. By the riot’s end, 26 were dead and 1,500 injured. Many feared that this level of violence spelled the beginnings of a coup d’état from the extreme right.

Crowds gather at Place de la Concorde, February 6, 1934. (BnF)

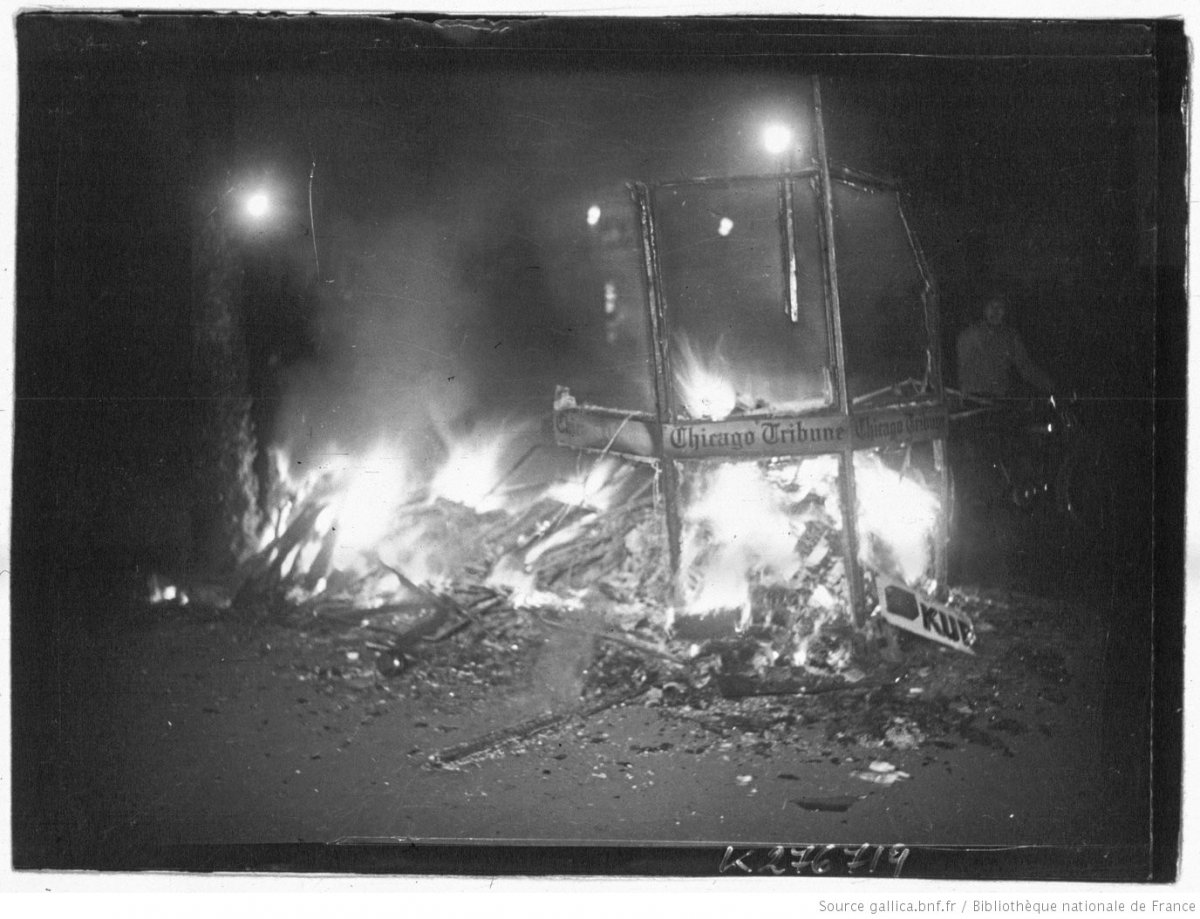

Newspaper Kiosk set on fire during the protests on February 6, 1934. (BnF)

While the protest unfolded, deputies had passed a vote of confidence in Prime Minister Édouard Daladier’s government. But based on advice from army and police officials and political advisors, Daladier stepped down to avoid increased violence. For the first time in the history of France’s Third Republic, street protests and fighting brought down the legally formed government.

The Third Republic persisted and the center-left Radical Party retained control of the government. However, street protests and violence continued in Paris and across major French cities. In fact, the riots of February 6th have become shorthand to describe the protests and violence that unfolded over the next week, the most violent period of political protest in France since the Commune of 1871.

The Paris Commune was a radical revolutionary government that controlled Paris for two months in 1871.

Protests had become even more frequent in the Interwar period. With the Great Depression arriving in France in 1932, politics became increasingly divided. As the decade unfolded, partisans on the right and left ardently defended their political beliefs as they attempted to resolve the mounting social and political discontent in France. Less and less space remained for compromise and moderates.

At its base, the protests were a reaction to the Stavisky Affair. Alexandre Stavisky, a man of Ukrainian Jewish descent, had been mired in political scandal after the public learned that he had used his connections to the Radical Party to issue fraudulent bank bonds.

The 1934 protestors initially took to the streets in reaction to the Stavisky Affair, in which Alexandre Stavisky had been accused of using connections to the Radical Party to issue fraudulent bank bonds.

In the climate of the Great Depression and the rising tide of xenophobia and anti-Semitism, his relatively minor swindling scheme garnered outsized attention. The press, especially newspapers affiliated with the political right, used the scandal as a rallying cry to blame Radicals for covering up Stavisky’s actions.

Given France’s political factionalism, and despite the focus on Stavisky, the February 6th protests had no clear goal. The vast majority of the protestors were members of far-right political organizations and nationalist veteran groups—many of whom advocated for more authoritarian governance in France—but they did not have a single leader around whom to rally.

Protestors block traffic—similar to the Gilets Jaunes today—on the Boulevard des Capucines on February 6, 1934. (BnF)

Yet, communists also participated in the protests. If February 6th drew the far right into the streets, a coalition of communists and socialists turned out in greater numbers on February 9th and 12th. Their participation highlights that it was not solely a movement for right-wing, authoritarian rule in France.

There were long-term political outcomes of these February demonstrations—a new coalition on the left, known as the Front Populaire, which won the 1936 elections. The widespread and grass-roots protests on February 12th signaled the beginnings of this new alliance between communists and socialists.

February 12, 1934, protestors with socialist deputies leading the march. (BnF)

As the decade unfolded, the political factions became further entrenched in their differences and took to the streets again and again to protest against the decisions of the other side. Unlike Germany and Italy, the French were able to hold off the complete collapse of the French Republic for the remainder of the 1930s, despite how close they came on February 6, 1934. But by July 1940, the Third Republic had been dissolved and, in its place, born from the political division of the previous decade, was an authoritarian government.

Elections in 1936 brought a leftist coalition known as the Front Populaire to power.

The February 6th protests are remembered for symbolizing the growing political divisions throughout Europe in the 1930s. Yet, the protests were also a profoundly French experience. “Aux barricades” (To the Barricades”) has been a familiar refrain in French protests across the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries—one which has been immortalized in popular imagination through descriptions of street protests and rebellion like those in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables.

Barricade erected by protestors on February 6, 1934. (BnF)

The barricades are an image that protestors use to garner more support and establish the validity of their movements to this day. Protestors in May 1968 built barricades to protect themselves and to proclaim that they would not back down.

For the past several months, the Yellow Vests—Gilets Jaunes—movement has convulsed France as protestors have taken to the streets upset with the cost of living.

Even more recently, the Yellow Vests Movement has been barricading streets every weekend since mid-November 2018 (and they have now been joined by counter-protests of the “Red Scarves”). Despite calling for the resignation of French President Emmanuel Macron, the Gilets Jaunes have not been as successful at forcing change as protestors in 1934.