The St. Louis No. 1 Cemetery sits on Basin Street, within the Tremé neighborhood and about a block north of New Orleans’s famed French Quarter. Completely walled in, the cemetery is unwelcoming. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans placed a ban on unescorted tourists in the cemetery in 2015 after an uptick in vandalism.

However, licensed tour guides of St. Louis No. 1 are always happy to show tourists the alleged tomb of Marie Laveau, legendary voodoo Queen of New Orleans, as well as the ostentatious pyramid purchased by actor Nicolas Cage for his future burial.

St. Louis No. 1 Cemetery, New Orleans.

Established in 1789, St. Louis No. 1 is the longest operating cemetery in New Orleans, yet it looks nothing like its portrayal in movies and television. After the cemetery’s less-than-respectful depiction in Easy Rider (1969), the Archdiocese banned filming in St. Louis No. 1 and filmmakers have turned to using the Garden District’s Lafayette Cemetery instead.

At St. Louis No. 1, there are no eerily beautiful angels fixed to mausoleums, welcoming the souls of the dead while simultaneously warning away the living. The photogenic pristine white tombs, so elegantly aged and garlanded by vines in Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, are obscured by rows of faded gray mausoleums and crumbling brick walls.

While many souls laid to rest since 1789 remain in their tombs, the walls of the cemetery are also lined with what tour guides call “condos”—stone mausoleums that grow so hot in the subtropical climate that the bodies of the dead within are rendered to little more than bone within a year. These remains are then moved to their family’s tomb, their desiccated ancestors swept to the back to make room for the new.

Either a holdover tradition from the city’s French founding or a necessary measure to counter a high-water table depending on who you ask, these above-ground mausoleums occupy little space and yet contain thousands of New Orleanians, etching the Cities of the Dead on the city’s landscape.

A tomb often mistaken for that of Marie Laveau, bearing graffiti Xs left by tourist making a wish to her spirit (left); “condos” at St. Louis No. 1 Cemetery (right).

Like St. Louis No. 1, New Orleans carries its history in its very bones, still bearing marks of the past on its infrastructure and layering lives lived to mingle the new with the old. A major New World port, New Orleans is a uniquely multicultural city.

Over a 100-year period, formal control of New Orleans changed hands three times: from France to Spain, then back to France, and then finally to the United States as a vital component of the Louisiana Purchase. During this period, a vibrant capitalist system developed along the river, lending French, Spanish, English, and African influences to the architecture, food, and music—all staples of modern New Orleans tourism.

In Jackson Square, war hero and American president Andrew Jackson stands guard over the St. Louis Cathedral (named for the child King of France), the Spanish Cabildo (the seat of the Spanish colonial government), and numerous restaurants serving Creole étouffée and po’boys.

In February, notorious Mardi Gras beads adorn lamp posts outside distinctive Creole townhouses and French Pontalba rows long past Fat Tuesday.

These infrastructural bones come with their own ghosts, haunting the streets of the city. While New Orleans has long pushed Louisianan Creole culture to the forefront of the city’s image, recognition of the slave trade that brought Africans to New Orleans is often relegated to the background.

A Pontalba Row building bearing an advertisement for Antoine's, the city's oldest restaurant, established in 1840.

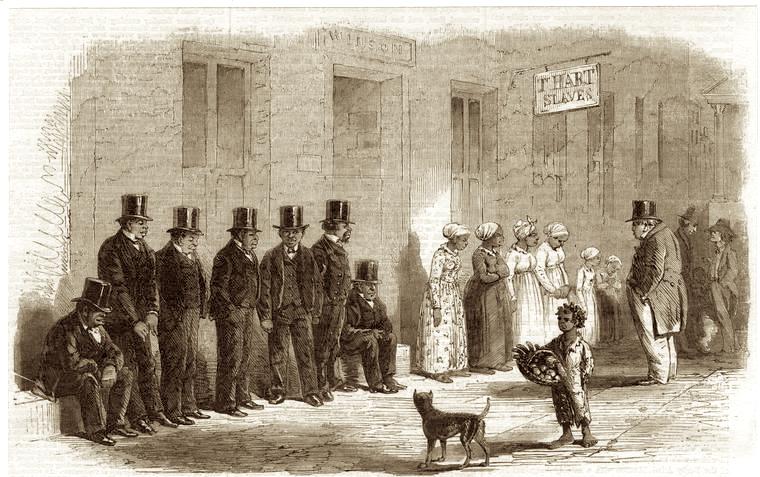

During the 19th century, New Orleans was a major hub of the American slave trade, with several thousand enslaved persons trafficked through the city and sold at auction at the St. Louis Hotel in the French Quarter, now renamed the Omni Royal.

Many slaves were kept in bondage in New Orleans, building many of the vital fixtures of the city. Others were sent to neighboring plantations that cultivated rice and sugar, crucial staple crops and brutal fixtures of Louisiana’s slave economy.

An 1861 illustration of enslaved women and children at auction in New Orleans

The dark history of the slave trade in Louisiana is often overlooked in favor of less violent aspects of antebellum history. Until recently, there was no recognition of the slave trade in the French Quarter and many of the plantations around the city have been converted to museums that sanitize elite white antebellum culture.

In recent years, however, New Orleans has taken strides to reckon with its history of racial violence. In 2018, the city erected plaques at key points around the French Quarter, recognizing New Orleans’s role in the American slave trade.

The Whitney Plantation seeks to tell the history of slavery in Louisiana.

Just outside the city, the Whitney Plantation opened in 2014. In stark contrast to the typical plantation museum, the Whitney is a Louisiana time capsule designed to preserve the history of slavery and to honor the victims of the slave trade.

Whitney tour guides escort visitors through the grounds of this once-profitable sugar plantation, showing the monuments erected to commemorate the names of the slaves who worked in their fields, the preserved slave quarters, and Coming Home, a statute dedicated to the children lost to the high infant mortality rate of American slavery. The Whitney is a devastating experience to visit, as informative as it is evocative.

Statues of children in the reconstructed slave quarters at the Whitney Plantation (left); "Coming Home," a memorial in honor of the thousands of enslaved children who died before reaching the age of three (right).

The tour guides at the Whitney are exceptionally knowledgeable, and are also adept at letting guests wrestle individually with the realities of American slavery. Crucially, this allows guests to recognize the racial inequality and violence that continue to haunt the streets of New Orleans as a specter of the slave trade — a legacy so often omitted from the image New Orleans projects in tourist hot spots like the French Quarter.

Like the tombs in St. Louis No. 1, the lives of New Orleanians throughout history are layered onto the streets of the city. These recent steps to recognize the lives that were pushed to the back allow us to recognize who New Orleans was, is, and what it can be.

A French Quarter Pontalba Row building.

[All photos by author, unless otherwise indicated]