In 1973, a 36-year-old Black woman named Nial Ruth Cox entered a North Carolina law firm with a record of her forced sterilization. Cox’s revelation ignited a shocking court case exposing decades of sterilization abuse in the name of eugenics.

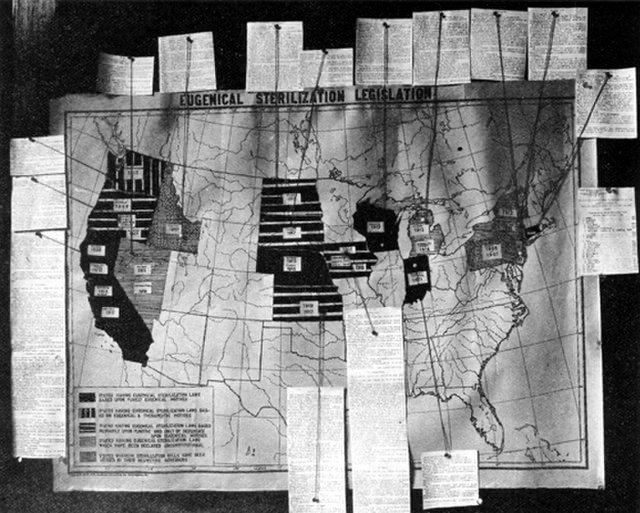

Eugenics boards in 33 states oversaw the sterilization of thousands of people between 1907 and 1977. Nearly all were classified as “feebleminded” and the procedure was often performed against their will or with coerced consent.

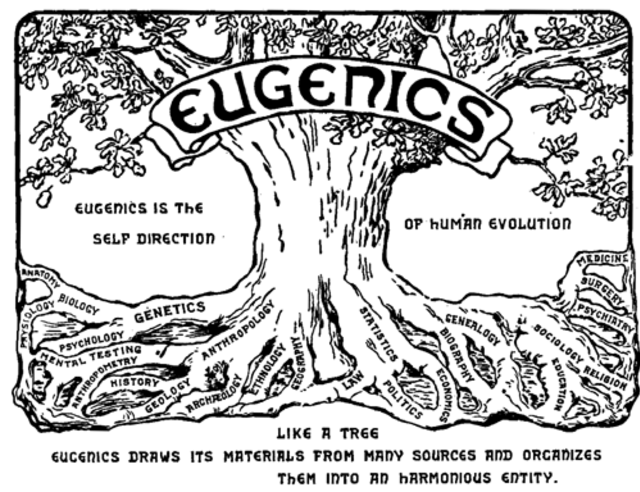

Eugenics, or the ideological demarcation between “fit” and “unfit” reproduction, drove the long history of forced sterilization in the United States. Among the many states with eugenics legislation, Virginia is infamous for its legal campaign to forcibly sterilize Carrie Buck and thereby entrench sterilization abuse as the law of the land.

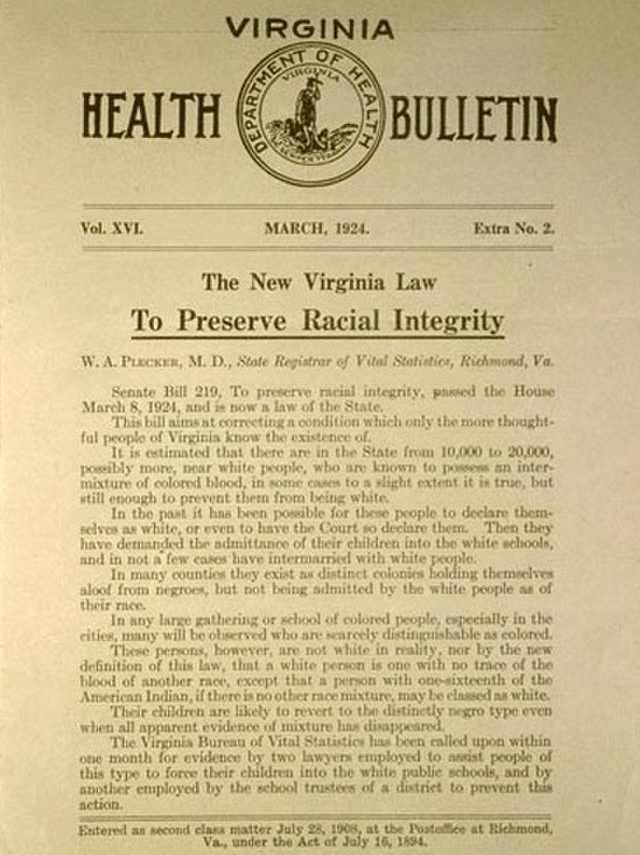

The legislative framework that made possible Carrie Buck's eventual court ordered sterilization took shape in a single afternoon. On March 20, 1924, the Virginia state legislature passed a series of devastating legislative initiatives.

The Virginia Sterilization Act provided for the sterilization of people deemed “feebleminded” or “socially inadequate”—two incredibly broad categories that could be stretched to include virtually any institutionalized or socially marginalized person.

Meanwhile, the Virginia Racial Integrity Act of 1924 “reified the idea of white purity by defining blacks as having one-sixteenth or more ‘negro blood’ and indigenous peoples as those having the same proportion of ‘Indian blood’,” in the words of Dorothy Roberts.

With its notions of racial purity thus established, the Racial Integrity Act also prohibited interracial marriage and specified that “the clerk or deputy clerk shall withhold the granting of the license” until the registrar’s office established the racial classification of each appellate. Together, these laws set the course for eugenics in Virginia.

Just three years later, in 1927, a seventeen-year-old white girl named Carrie Buck was at the center of debates about the state’s sterilization law.

Buck was a resident of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, where her foster family abandoned her when she became pregnant as a result of rape. For Buck’s foster family and the doctors who recommended sterilization, a pregnancy out of wedlock was one of the “eugenic symptoms of inherent immorality.”

Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes upheld this view when he specified Buck could not choose for herself whether to be sterilized because “she is further incapacitated by congenital mental defect.” Over Buck’s objections, the Court recommended that she be sterilized because, according to the last line of their decision, “three generations of imbeciles is enough.”

Buck was sterilized on October 19, 1927, soon after the Supreme Court’s ominous ruling.

A series of letters from Buck to Dr. John Bell and a nurse between 1927 and 1934, reveal her awareness that she was akin to a “furloughed inmate … on parole.” Until her marriage in 1932, she remained a ward of her employers for whom she provided live-in domestic work for the paltry sum of $5 per month. During this time, she could be recalled to the Colony for any perceived infraction.

After Carrie Buck’s forced sterilization, the number of states with legal provisions for the sterilization of “feebleminded” and “criminals” ballooned. In several states, women were institutionalized at much higher rates than men for the express purpose of being sterilized.

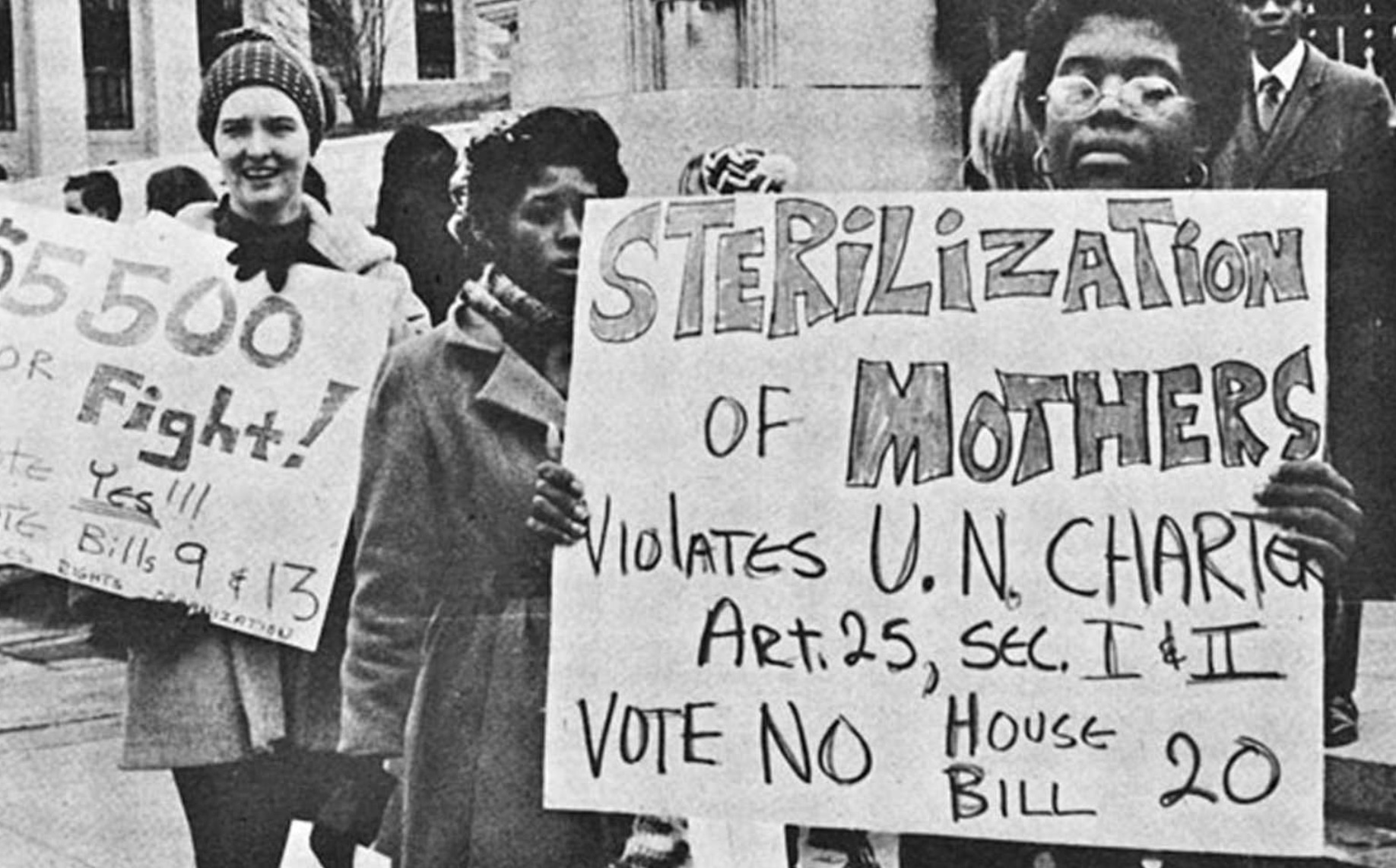

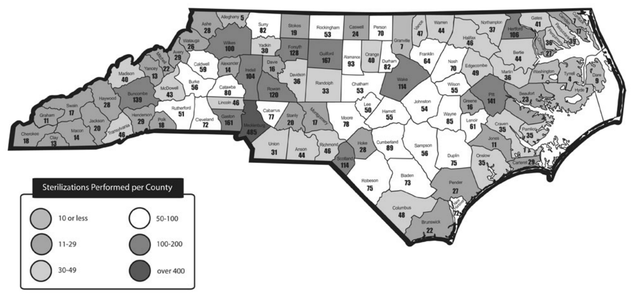

In the records available, women of color were forcibly sterilized at much higher rates than white women. For example, in North Carolina, African American women accounted for 64.8% of those sterilized by the eugenics board between 1964 and 1966, a rate more than five times their population representation.

The issue of sterilization abuse and its disproportionate impact on women of color became a rallying point for feminists of color in the 1960s and 1970s.

Groups such as the Boston-based Black lesbian feminist Combahee River Collective placed anti-sterilization activism prominently among their commitments. The group’s mission statement in 1977 noted: “Issues and projects that collective members have actually worked on are sterilization abuse, abortion rights, battered women, rape, and healthcare.”

Their inclusion of anti-sterilization activism in their struggle “against racial, sexual, heterosexual and class oppression” is instructive for challenging contemporary sterilization abuse and understanding the legacies of Carrie Buck’s sterilization after the Buck v. Bell ruling in 1927.

While eugenic ideas have a long and troubling history in the United States, these beliefs continue to negatively impact people today. Existing laws continue to steal away reproductive autonomy and subject people to forced sterilization, especially women of color, disabled, and incarcerated women.

A report by the National Women’s Law Center and the Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network found that 31 states and Washington D.C. allowed forced sterilization of disabled people in 2021. The report describes these laws as antithetical to disabled people’s right to make decisions about their bodies. It also contains the haunting revelation that Black disabled women are more likely to be sterilized than white disabled women. Other reports document the forced sterilization of immigrant women in detention centers and incarcerated women.

Almost a century after Buck’s sterilization, few states have issued formal apologies for the many thousands forcibly sterilized under eugenic statutes. North Carolina, California, and Virginia alone authorized reparations for survivors of sterilization.

For their part, survivors and their allies oscillate between relief at public recognition after often decades-long battles to raise awareness and a hollow sense that no compensation could ever replace what was stolen from them.

![]()

Learn More:

Dorr, Gregory Michael. Segregation’s Science: Eugenics and Society in Virginia. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008.

Fields, Karen E. and Barbara Jeanne Fields. Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life. New York: Verso, 2012.

Roberts, Dorothy. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-First Century. New York: New Press, 2011.

Sherman, Shantella. "In Search of Purity: Popular Eugenics and Racial Uplift among New Negroes 1915-1935" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/68.

“Wangui Muigai” in Projit B. Mukharji, et. Al. “Open Conversations: Diversifying the Discipline or Disciplining Diversity: A Roundtable Discussion on Collecting Demographic Data,” Isis 111 no. 2 (2020): 310-353