One of the most beautiful parts of the former Soviet Union—Nagorno-Karabakh—has recently been scarred by violence and remains trapped in a frozen conflict. Tucked away in the South Caucasus near the frontiers of Russia, Iran, and Turkey, this gorgeous mountain land boasts stunning alpine scenery, lush forests, and numerous historical monuments and churches. Sadly, it has become the center of a major feud between Armenians and Azerbaijanis.

Location of Nagorno-Karabakh highlighted within the post-Soviet Caucasus. Map by this writer, based on 1995 CIA ethnolinguistic map of the Caucasus (left), and Mountainous landscape of Nagorno-Karabakh.

During the Soviet era, the Nagorno-Karabakh region was part of the Azerbaijan republic but had a majority Armenian population. At the end of the Soviet era, the region’s Armenian inhabitants began a movement for the reunification of Nagorno-Karabakh with the Soviet Armenian republic in accordance with Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost and perestroika. The area soon became a flashpoint for conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis.

Following the collapse of the USSR in 1991, a war erupted over the contested territory, causing thousands of deaths and hundreds of thousands of refugees on both sides. The Karabakh Armenians declared their own republic and achieved de facto independence from Azerbaijan. A 1994 Russian-brokered ceasefire remains in place but is tenuously enforced. In April 2016, hostilities in this region again exploded in a four-day war amid a larger regional tussle between Russia and Turkey over Syria. Tensions along the ceasefire line between the Yerevan-backed Karabakh Armenians and the Azerbaijani Army remain high.

A view of Azatamartikneri (Freedom Fighters') boulevard, Stepanakert.

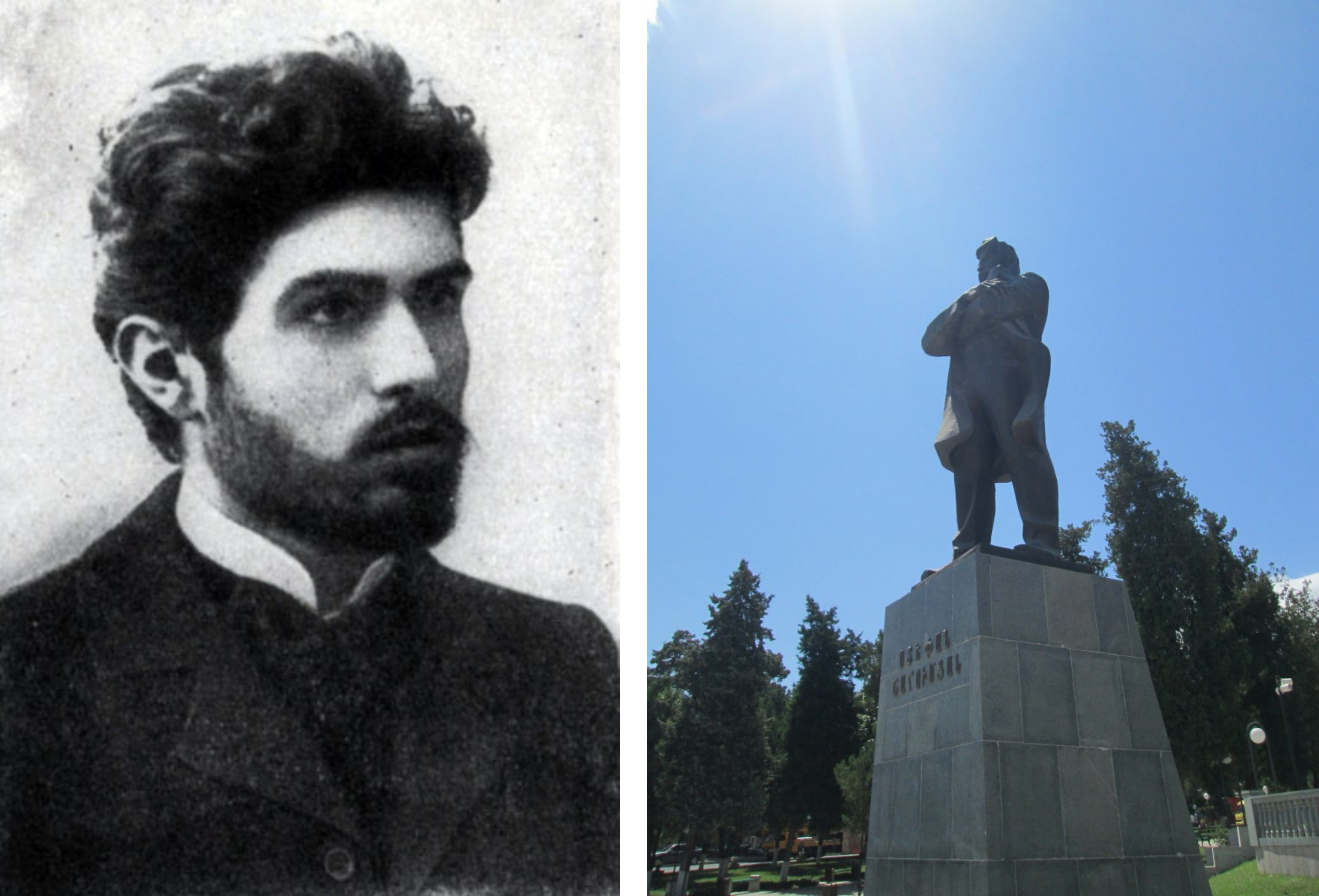

Today the self-proclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh Republic is a safe place to travel, despite the news reports of war. The local people are friendly, hospitable, and speak a colorful and distinctive dialect of Armenian that even native Armenian speakers have difficulty understanding. The region is known for its wine and mulberry vodka. Jingalov hats, a flatbread stuffed with vegetables, is a staple of Karabakh cuisine. Stepanakert, the region’s capital, is named after Armenian Bolshevik revolutionary Stepan Shahumyan, an ally of Lenin.

Stepan Shahumyan, the Armenian Bolshevik revolutionary and the namesake of Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh (left), and a statue of Stepan Shahumyan in Stepanakert.

At the time of this writer’s visit in 2014, life in the capital and other cities appeared to be relatively prosperous. On the streets, people were well-dressed and the apartments and houses were in fine condition. The economy appeared to be doing quite well in this small, self-styled republic. One local citizen even boasted of the low unemployment in Karabakh compared to neighboring Armenia.

Nagorno-Karabakh is home to many historical monuments. In Shushi, the main attraction is the magnificent Ghazanchetsots Cathedral. Nearby is the ruined Yukhari Govhar Agha Mosque. Other sites of interest include the 9th Century Dadivank monastery, the 10th Century Gandzasar Monastery, and the 4th Century Amaras Monastery established by St. Gregory the Illuminator. It was at Amaras that St. Mesrob Mashtots, the inventor of the Armenian alphabet, first taught his sacred script.

Ghazanchetsots Cathedral, Shushi.

Yukhari Govhar Agha Mosque, Shushi.

However, perhaps the most symbolic monument of the region is the massive We Are Our Mountains (or Tatik u Papik) monument. Carved from volcanic tuff by Soviet Armenian People’s Artist Sargis Baghdasaryan, it presents a stylized depiction of an elderly Karabakh Armenian couple. It is a monument to the resilience of the people of this mountainous land and their aspiration for peace.

We Are Our Mountains (Tatik u Papik) Monument, Stepanakert.

The Black Garden: What’s in a Name?

The very name Nagorno-Karabakh attests to the region’s checkered political history as a contested zone among rival empires. The “Nagorno” part is Russian for “mountainous.” “Karabakh” is a name of seemingly mixed Turkish-Persian origin, with “kara” being Turkish for “black,” and “bakh” being Persian for “garden,” therefore meaning “black garden.”

However, as Karabakh scholar Emil Sanamyan writes, “there is no academic consensus about that interpretation,” because the Turkish “kara” can alternatively be translated as “rich,” as in “rich in gardens.” Armenians know the region by its historical Armenian name, Artsakh.

The Roots of Conflict: A Complicated Past

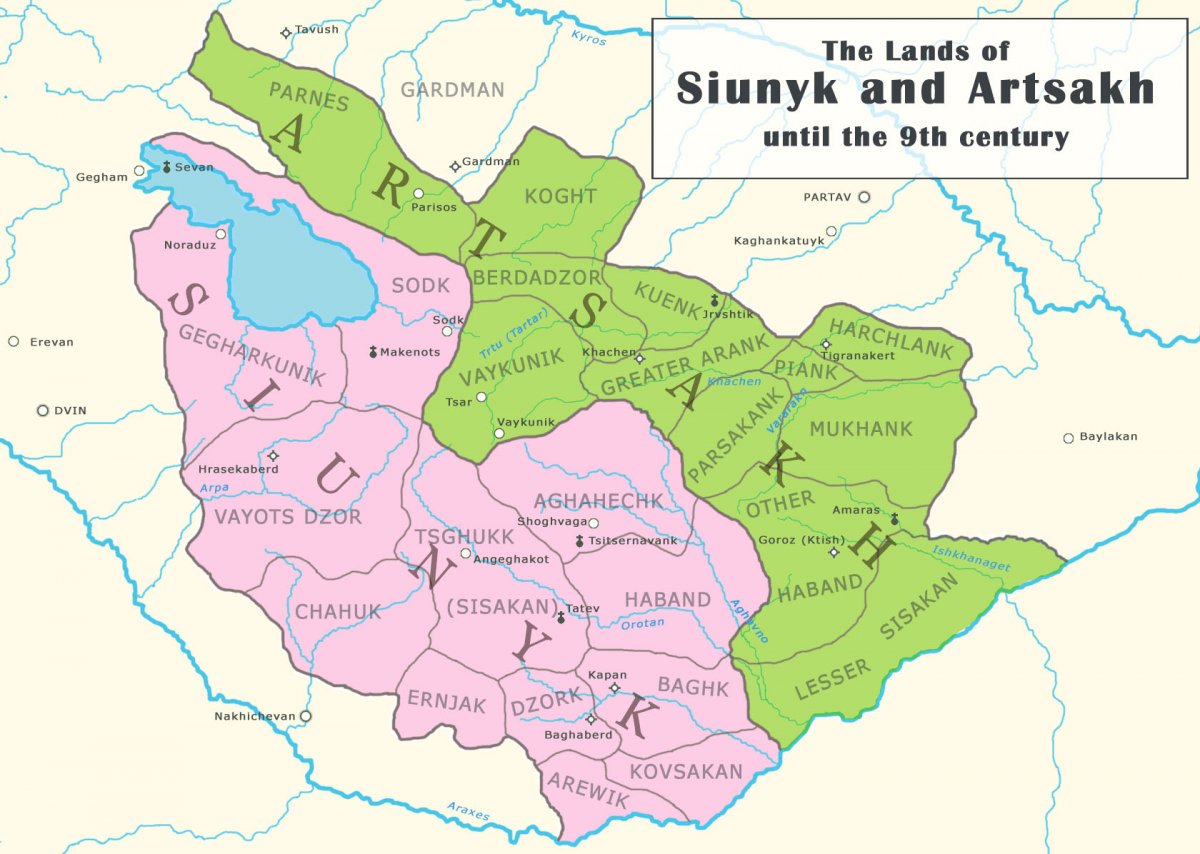

The historic lands of Syunik and Artsakh.

A natural highland mountain fortress, Artsakh was a proudly independent principality within the Kingdom of Armenia for many centuries. It enjoyed particularly close ties with the neighboring Armenian principality of Syunik. After the fall of the Bagratuni Kingdom of Armenia in 1045 and later the Georgian-sponsored Zakarid Armenian Kingdom, Syunik and Artsakh (by now known as Khachen) remained among the few places where Armenian secular political leadership and institutions persisted. In fact, it can be said that Syunik and Khachen were to Armenia what Piedmont-Sardinia was to Italy, i.e., a focal point for national unification.

It was the princes (meliks) of these eastern Armenian provinces who made the initial contact with Russian Tsar Peter the Great to liberate their lands from Persian suzerainty. Unfortunately, Peter’s 1722-23 Caucasian expedition was beset by difficulties and the Tsar had no choice but to ultimately withdraw from the region. This left the Armenians and Georgians, who sought an alliance with Peter, to resist against an invading Ottoman army.

Iranian influence over the region was restored by the great Persian leader Nader Shah. As part of the Shah’s strategy of cultivating loyalty among communities on Iran’s frontiers, he ensured the autonomy of the Armenian princes of Syunik and Khachen. However, after his death in 1747, these princes became engulfed in infighting. The fatal blow came when one Armenian prince invited Panah-Ali Khan Javanshir of the neighboring Turkic Muslim Karabakh Khanate to enter the territory and add it to his domain.

Russian Tsar Peter the Great (left), and Persian ruler Nader Shah on horseback (right).

Henceforth, the region of Khachen became known as Mountainous Karabakh. The majority-Armenian territory was distinguished both geographically and ethnographically from Shia Muslim and Turkic-speaking Lowland Karabakh.

Following the Russian annexation of the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti in 1801, the Karabakh Khanate first became a protectorate of Russia and was later annexed outright from Iran. The region was subsequently ruled as part of Russian Transcaucasia for the next century.

Map of Russian Armenia and Mountainous Karabakh within Russian Transcaucasia from Karte der Kaukasus-Länder by Henry Lange in the German edition of Baron August von Haxthausen's Transcaucasia (Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1856). Note that Mountainous Karabakh is delineated separately from "Armenian" and "Tatar" (today Azerbaijani) territory, although the city of Shushi (Shusha) is curiously located outside of it. (Courtesy of the John G. White Special Collection of Folklore, Orientalia, and Chess at the Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland.)

With the collapse of tsarist authority in the Caucasus following the 1917 Russian Revolution, Mountainous Karabakh again became a point of conflict, this time between the short-lived independent republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan. By the time of the Sovietization of Transcaucasia in 1920, the Azerbaijanis had gained control of Mountainous Karabakh, despite its Armenian majority.

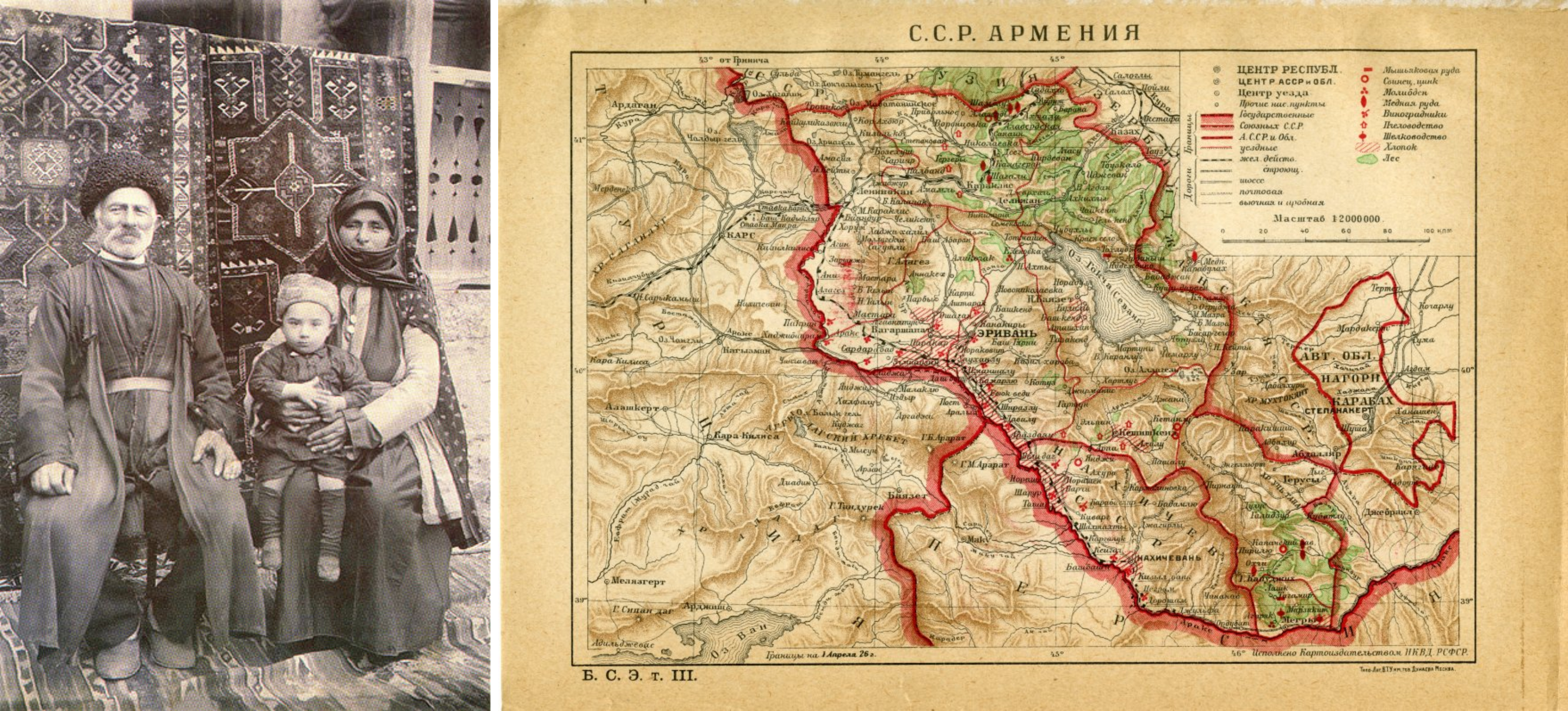

Armenian family in Nagorno-Karabakh, late 19th or early 20th century (left), and Map of Soviet Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonmous Oblast from the first edition of The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, edited by Otto Schmidt (Moscow: Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, 1926). (Courtesy of the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.)

In February 1921, an anti-Soviet rebellion broke out in the neighboring Armenian region of Syunik. Hoping to crush this rebellion and gain popular support, the Bolsheviks promised to cede Mountainous Karabakh to Soviet Armenia. The Caucasus Bureau even voted in favor of this decision on 4 July 1921.

However, literally the next day, the decision was reversed. According to historian and Karabakh specialist Arsène Saparov, the reversal was primarily due to the fact that the rebellion in Syunik had just been successfully defeated. Moreover, the Azerbaijanis continued to remain in control of Mountainous Karabakh. Bolshevik Azerbaijani leader Nariman Narimanov used this circumstance, and Baku’s oil supplies, as leverage in arguing that the region should remain under Azerbaijani control.

Primarily interested in stabilizing and securing control of the region, the Bolsheviks accepted Azerbaijani control of Mountainous Karabakh, but granted the concession of local autonomy to the Armenian population. This resolution left both sides unsatisfied and ultimately led to the outbreak of violence at the end of the Soviet era and eventually war in the 1990s.

The author in Shushi with the statue of Vazgen Sargsyan, Karabakh War military commander and the future Prime Minister of Armenia.

Gagik Avsharyan T-72 Tank Memorial, Shushi, Nagorno-Karabakh.

Nagorno-Karabakh Today

Today, the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh remains tense. Negotiations, mediated by the United States, Russia, and France are ongoing. Within the Caucasus neighborhood, Russia and Iran are primarily interested in a resolution of the conflict in the interests of regional stability. "Russia wants to avoid a further escalation in Karabakh,” noted Caucasus analyst Sergey Markedonov. For its part, Iran was particularly alarmed about cross-border shelling into its territory during the 2016 war.

Turkey seeks a resolution as well, but only on Azerbaijani terms, a position rejected by Armenia and the Karabakh Armenians. An ongoing Turkish and Azerbaijani blockade of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh only further complicates the prospects for peace. Azerbaijan’s Caspian oil supplies add to the intrigue.

Street art in Shushi, Nagorno-Karabakh.

National Assembly Building, Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh.

Ultimately, a resolution will require a peace between the societies and political leaderships of both countries. The road to such a peace is not easy, albeit not impossible. Armenians and Azerbaijanis can co-exist, but need to overcome negative perceptions of the “other.”

[All photos by author unless otherwise noted]