Russia’s cooperation with the Kurds of Iraq and Syria in the fight against ISIL has been widely publicized by the Western media. However, less well-known is the fact that Russia’s relations with various Kurdish groups date back almost two centuries.

Spread across the mountainous frontiers of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, the Kurds number approximately 30 million people. Although united in a struggle for civil and political rights, they comprise various tribal affiliations and speak different dialects. Most Kurds are Muslim (primarily Sunni, but also Shia). Some are adherents of the Yazidi faith, a religion that shares common elements with Christianity, Islam, and Zoroastrianism.

Russia’s southern expansion (from the 18th century on) in search of secure borders and natural resources brought it into contact with different Kurdish tribes. Since then, Moscow has maintained relations with Kurds both inside and outside of its borders. This history forms an important part of Russia’s relationship with the Middle East and underscores its unique position between Europe and Asia. Below are 10 of the most significant moments in Russian-Kurdish relations, from Pushkin to the Peshmerga.

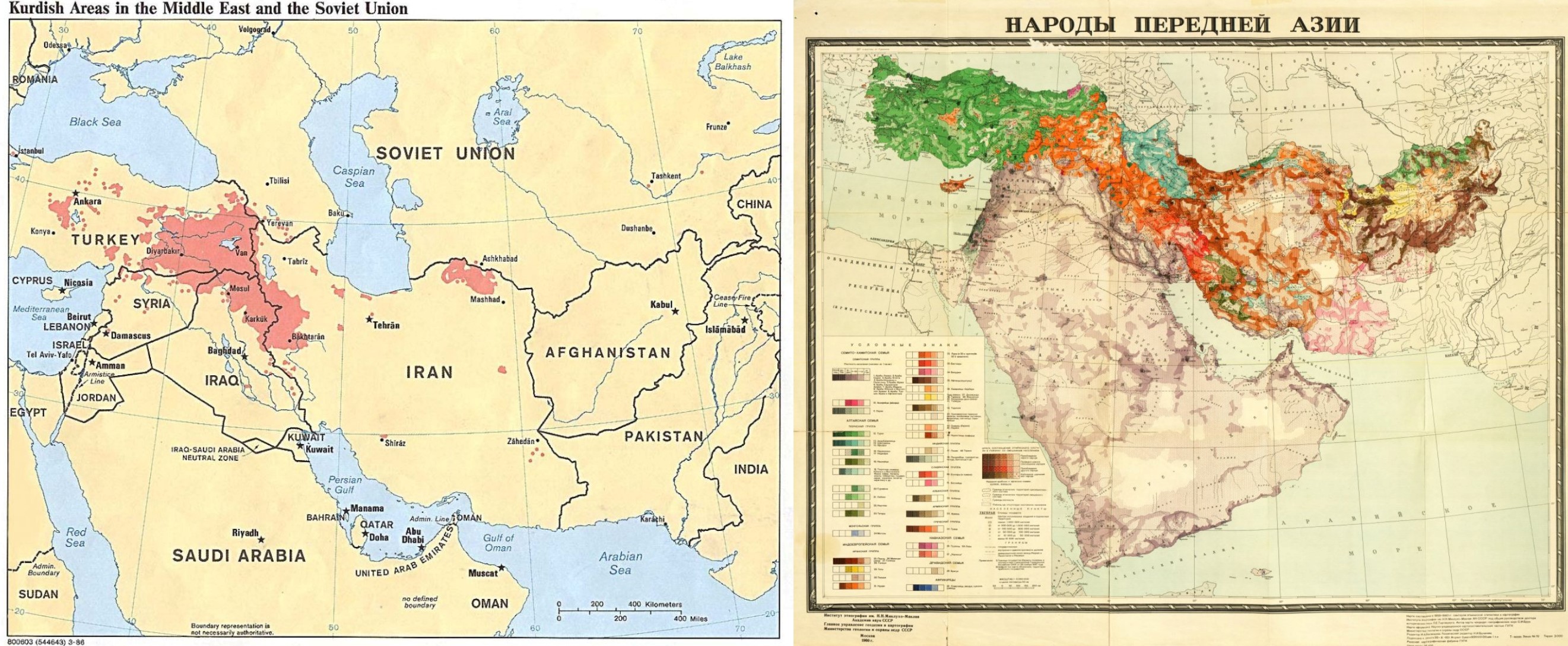

1986 CIA map of Kurdish-inhabited areas in the Middle East and the Soviet Union (left), and 1960 Soviet ethnographic map of the Near East with Kurdish populations in orange. (Courtesy of the Stephen S. Clark Library at the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.) For more maps of the Kurdistan region, see the work by Dr. Mehrdad Izady at the Gulf/2000 Project at Columbia University here.

1. The Poet and the Peacock People

Self-portrait of Aleksandr Pushkin on horseback, 1829, from the Ardis republication of the 1934 edition of Pushkin's Journey to Arzrum assembled by Russian émigré ballet dancer and choreographer, Serge Lifar. (Image from author's personal collection, courtesy of the John G. White Special Collection of Folklore, Orientalia, and Chess at the Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland.)

Russia’s conquest of the Caucasus brought several new ethnic groups into the tsarist state. Among them were many Yazidi Kurds, also known as the “peacock people” due to Melek Taus, the “Peacock Angel,” one of the central figures in their faith. While accompanying the Russian military during the 1829 Turkish campaign, the Russian poet Aleksandr Pushkin encountered a detachment of Yazidis in the Russian army. “There are about three hundred families [of Yazidis] who live at the foot of Mount Ararat,” Pushkin wrote in his Journey to Arzrum. ‘They have recognized the rule of the Russian sovereign.” From Yazidi chief Hasan Aga, “a tall monster of a man in a red tunic and black cap,” Pushkin learned about the particulars of the Yazidi faith. After exchanging these pleasant tidings with the curious Yazidis, the poet was relieved to find that they were far from being the “devil-worshippers” that many claimed.

2. Khachatur Abovian, Armenian Founder of Russian Kurdology

Abovian Among the Kurds, painting by Mkrtich Sedrakyan, 1950. (Image from author's personal collection, courtesy of the Khachatur Abovian House-Museum, Yerevan, Armenia.)

Celebrated Armenian writer Khachatur Abovian was the founder of Kurdish Studies in Russia. Educated at Dorpat (present-day Tartu, Estonia) on the invitation of Friedrich Parrot, he was the first Armenian author to write in the Armenian vernacular as opposed to Classical Armenian. Although a major Armenian national figure, Abovian’s outlook was universal. His wife was German and he recorded Kurdish and Azerbaijani Tatar folklore in Armenia.

Abovian quickly became a “trusted friend” of the Yazidis and Kurds. He wrote extensively about their life and customs, though he erroneously contended that the Yazidi faith was a heretical offshoot of the Armenian Church. In 1844, Hasanli Yazidi chief Timur Aga was invited by Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, the new viceroy of Russian Transcaucasia, to a banquet with Kurdish and Turkish tribal leaders in Tiflis. After returning to his tribe with a gift from Vorontsov, the chief held a feast and invited Abovian to attend.

3. Red Kurdistan

Following the Sovietization of the Caucasus, Soviet authorities began delineating national boundaries according to the Soviet nationality policy. In 1923, the Kurds of Soviet Azerbaijan sandwiched between Soviet Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, were granted their own district by Baku with its center at Lachin. Officially known as the Kurdistan Uezd (“Red Kurdistan” or “Kurdistana Sor”), it was not formally autonomous and the Soviet Azerbaijani government did little to promote Kurdish culture.

According to the 1926 Soviet Census, 72% of the population were Kurds, although most of them spoke Azerbaijani Tatar as their first language. The uezd was abolished in 1929 alongside other Azerbaijani uezds, but was briefly revived in 1930 as the Kurdistan Okrug, before being divided into districts. In subsequent decades, the Kurds of this region were assimilated into the Azerbaijani population, while other Azerbaijani Kurds were deported by Soviet authorities to Central Asia under Stalin in 1937.

4. Zare – The First Kurdish Film

Zare (1926), the first Kurdish film, was produced in the Soviet Union by Armenkino, the Soviet Armenian film studio. It is about a young Yazidi Kurdish girl, Zare, and her love for the shepherd Saydo on the eve of the Russian Revolution. Unfortunately for Zare and Saydo, they have to fight for their love against a licentious bek (local noble), a corrupt tsarist Russian bureaucracy, and local social patriarchy. The film was directed by Amo Bek-Nazaryan in the era of the Soviet New Economic Policy (NEP), which saw the rise of avant-garde filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein. Bek-Nazaryan praised Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), released a year earlier. “In his wonderful movie,” wrote Bek-Nazaryan, “Eisenstein boldly used not only actors, but also people previously not connected to theatre or cinema, but whose appearances meet his artistic vision… In Zare, I was forced to do the same.” The film remains a classic of Kurdish cinema.

5. The Kurdish Republic of Mahabad

Mahabad (2017). Short documentary film from the Kurdistan Memory Programme.

In 1941, wartime allies Britain and the Soviet Union invaded Iran to secure crucial Allied supply lines. Iranian leader Reza Shah, who harbored sympathies for the Axis Powers, was overthrown by the Allies and his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was placed on the throne. Iran remained occupied for the duration of the war, with the USSR occupying the northern half of the country and Britain the southern half.

At the end of the war, Moscow refused to leave its zone of influence and began to sponsor breakaway republics in Iranian Azerbaijan and Iranian Kurdistan. The latter republic was established at Mahabad in 1946. Qazi Mohammad served as its president, and Mustafa Barzani, the Kurdish rebel leader from Iraq, served as its Minister of War. The euphoria of this Kurdish republic was short-lived. Stalin withdrew support after Moscow secured oil concessions from the West. The Mahabad republic was subsequently crushed by Tehran.

6. A Kurdish Rebel in Exile

After Tehran retook Mahabad, Mustafa Barzani and his followers fled north, across the Aras River, into Soviet Transcaucasia in June 1947. There they engaged in training and Barzani learned fluent Russian. Initially hosted by Soviet Azerbaijan, Barzani had a disagreement with Soviet Azerbaijani leader Mir Jafar Bagirov, a close ally of Lavrentiy Beria, who attempted to control Barzani and his followers. They were transferred by Moscow to Soviet Uzbekistan in 1948. However, the group did not escape Bagirov’s wrath and were dispersed throughout the Soviet Union.

Reunited in 1951, their situation improved dramatically after the deaths of Stalin and Beria in 1953. Barzani met with Nikita Khrushchev, who was reportedly impressed with the Kurdish leader, and he went to the Frunze Military Academy. Deeply appreciative of Moscow’s assistance, the Barzanis returned to Iraq in 1958. Moscow still enjoys good relations with the Barzanis, including Barzani’s son, Masoud, former president of Iraqi Kurdistan.

7. Kurdish Culture in the Soviet Union

Photograph of Kurdish listeners of Radio Yerevan, 1955. (Image from author's personal collection, courtesy of Dr. Jalile Jalil and Zeri İnanç.)

The Soviet Union played a vital role in preserving Kurdish culture. In the drive toward mass literacy, Kurds and Yazidis in Soviet Armenia learned their language in three alphabets – first Armenian, then Latin, and finally Cyrillic. Armenia became a major center for Kurdish-language publications, including the newspaper Riya Taze (New Path) and several children’s books. The first Kurdish novel, written by Soviet Yazidi author Ereb Shamilov, was published in Yerevan in 1935.

Kurdish-language broadcasts by Radio Yerevan began in 1955 and had a major impact on Kurds beyond the borders of the USSR. Kurds in neighboring countries, especially Turkey, picked up the Soviet transmissions and were delighted to hear their native language, which was heavily repressed elsewhere. The broadcasts were crucial for the development of Kurdish ethnic self-awareness, and the socialist message of the Soviet Union strongly resonated among many Kurds. Soviet Kurds also proudly served the USSR in World War II.

8. Kurds and Yazidis in the Post-Soviet States

After the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, the Kurds of the region became divided among the newly independent states of Eurasia. The Kurds of Russia are both Muslim and Yazidi and are primarily concentrated in the North Caucasus, especially in the Krasnodar Krai. In Georgia, they are mostly concentrated in Tbilisi and there is also a significant Kurdish population in post-Soviet Central Asia.

Yazidis form the largest ethnic minority in Armenia and are located in different provinces, most notably in Armavir, Aragatsotn, and Ararat. Many fought alongside Armenians in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Divided on identity, some post-Soviet Yazidis see themselves as a subgroup of Kurds, while others see themselves as a separate ethnic group. Currently, the largest Yazidi temple in the world is under construction in Armenia. Yazidis have representation in the Armenian and Georgian parliaments and both Armenia and Georgia have accepted Yazidi refugees who are fleeing persecution by ISIL.

9. Russia Allies with Syrian and Iraqi Kurds against ISIL

Syrian Kurds open a diplomatic mission in Moscow. Footage from Ruptly, February 10, 2016.

Russia is allied with the Syrian and Iraqi Kurds in the fight against ISIL. After the shootdown of the Russian Sukhoi-24 plane by Turkey over the Turkish-Syrian border, Moscow enhanced its relations with representatives of the Kurdish communities in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. It has maintained these ties even as its relationship with Ankara improved. Allies of both Washington and Moscow, the Syrian Kurds have managed to bring the two powers together against ISIL.

However, as the Syrian Civil War comes to a close, new questions arise regarding the post-war peace. Damascus has signaled its openness to devolving power to the Syrian Kurds through political autonomy. However, the Syrian Kurds prefer a federal system for Syria based on direct democratic representation. Russian President Vladimir Putin expressed support for convening an all-Syrian peace congress with “all ethnic and religious groups.” On October 31, Moscow invited the Kurds to participate in this congress.

10. Russia and the Iraqi Kurdish Independence Referendum

On September 25, 2017, the Kurds of Iraq held a referendum on political independence from Baghdad, which 92.3% of the population supported. The result provoked an angry response from the Iraqi central government, supported by Turkey and Iran. The tension culminated in Baghdad’s capture of the oil-rich city of Kirkuk.

Russia was restrained in its reaction to the referendum. Although it “respected the national aspirations of the Kurds,” it simultaneously encouraged dialogue between Erbil and Baghdad. Significantly, Russia was the only major power that did not call on the Iraqi Kurds to cancel the referendum. In addition to Moscow’s historical ties to the Barzani clan, it is the top funder of Iraqi Kurdish gas and oil deals. Russia has emphasized that cooperation in the energy sphere remains unaffected by the referendum. On October 18, Russian energy giant Rosneft signed an energy deal with Iraqi Kurdistan, reaffirming its commitment to the region.

BONUS: Aram Khachaturian's Saber Dance

Soviet Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian is regarded as one of the three “titans” of Soviet music, alongside Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergey Prokofiev. One of his most famous ballets, Gayane, involves Kurdish characters and themes. Completed at the outbreak of World War II, it featured a libretto by Konstantin Derzhavin and choreography by Nina Anisimova, Derzhavin’s wife. The original libretto was an interethnic love story involving Armenians, Kurds, and Russians, set against the backdrop of a mountainous kolkhoz (collective farm) in Soviet Armenia, on the Soviet-Turkish frontier.

The ballet is best known for Khachaturian’s fiery Saber Dance, which he originally called “the Dance of the Kurds.” In November 1942, Khachaturian wrote that he started composing the melody “at three in the afternoon and worked until two AM.” When it was performed at a dress rehearsal the following evening, the composer noted that it “immediately impressed the orchestra, the dancers, and the audience.”