On June 18, 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte's forces were defeated at Waterloo by the armies of the Seventh Coalition, led by the British Duke of Wellington and Prussia's Marshall von Blücher. This fateful encounter doomed Napoleon's brief restoration as Emperor of France and preserved the balance of power that Europe's traditional monarchs had just struck at the Congress of Vienna.

It also marked the end of two decades of nearly continual warfare that had cost millions of lives, ushering in a period of peace across most of Europe that would go largely unbroken for the next century.

| The Battle of Waterloo, 1815 |

In twenty-first century Europe, the ramifications and legacy of Waterloo still remain the subject of heated debate.

In February 2015, Belgium proposed a specially minted euro coin to celebrate the bicentennial of the battle, which took place some ten miles south of Brussels. However, these plans were stymied by the French government, who claimed it was "prejudicial" to elevate "a symbol that is negative for a fraction of the European population."

|

| France rejected Belgium's plans to make a special-edition euro coin commemorating the Battle of Waterloo. Belgium still proceeded to mint the above non eurozone circulating €2.5 coin. |

France's objections generated widespread international ridicule, particularly in the United Kingdom. "Water-boo," crowed The Sun. "Just for once, France DOESN'T surrender," sneered The Daily Mail. One Conservative politician decried the French lack of respect for "a momentous event in Europe’s history and an important one for freedom and democracy."

These cross-Channel jibes are especially striking given that Britain, which left the European Union after a contentious 2016 referendum, never actually used the euro. As one pro-Brexit politician put it, "I know the euro is a useless currency, but I didn’t know that the French still could not cope with the fact they were defeated."

In the years since the battle different groups have disagreed over just how significant the fighting really was and what its legacy has meant.

|

|

| These two paintings, The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries (left) and Napoleon Abdicating in Fortinbleau (right), represent very different portrayals of Napoleon. |

The challenge of interpreting Waterloo began almost as soon as the guns fell silent. Napoleon himself published the first French-language account of the battle. Over the succeeding years, his subordinates, acolytes and detractors all put their own accounts to paper – as did his British, German, and Dutch adversaries. The growing European literacy rate not only led to an unprecedented number of witness accounts from soldiers and civilians who had lived through the wars, but also guaranteed a large, engaged audience for published works.

More tangible reminders of the battle also proliferated throughout Europe. These ranged from the monumental, such as Wellington's Column in Liverpool and the various public spaces named after Waterloo in London, to the practical and even macabre – witness the popularity of so-called "Waterloo teeth," denture sets (right) made using the scavenged molars of fallen soldiers.

For many observers, passing judgment on Waterloo meant also judging the two decades of revolution, war and empire that had preceded it.

In defeating Napoleon, did Wellington's men "rescue innocence from overthrow" and "trample down … tyrannic might," as Sir Walter Scott wrote in "The Fields of Waterloo"? Or was Waterloo, as Victor Hugo would have us believe a "counter-revolutionary" yet ultimately pyrrhic victory, which "by cutting short the demolition of European thrones by the sword, had no other effect than to cause the revolutionary work to be continued in another direction"?

In the twentieth century, Waterloo's meaning has continued to reflect contemporary political circumstances.

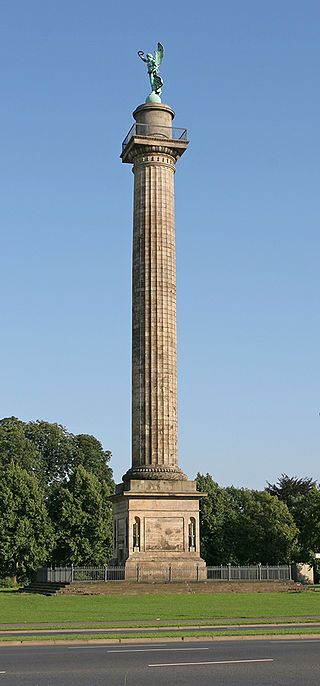

Thus, the 1915 centennial was a muted affair in Britain – not only because British soldiers were once more fighting and dying on the continent in great numbers, but also so as to avoid embarrassing France, their erstwhile foe and present ally. German commemorations, however, showed no such compunction; in Hanover, 100,000 people gathered at the Waterloo Column (left) to celebrate Germany's role in liberating Europe one hundred years earlier. For their part, the French framed Waterloo as more proof that the Germans were a "predatory race" who must be stopped at all costs.

Thus, the 1915 centennial was a muted affair in Britain – not only because British soldiers were once more fighting and dying on the continent in great numbers, but also so as to avoid embarrassing France, their erstwhile foe and present ally. German commemorations, however, showed no such compunction; in Hanover, 100,000 people gathered at the Waterloo Column (left) to celebrate Germany's role in liberating Europe one hundred years earlier. For their part, the French framed Waterloo as more proof that the Germans were a "predatory race" who must be stopped at all costs.

After 1945, Waterloo and other major historical events began to be seen as the potential foundation for greater European unity around a shared heritage.

For example, a British memorial ceremony in Belgium on the battle's sesquicentennial in 1965 honored the soldiers of all nations who had died at Waterloo, and attracted diplomatic representatives from Germany and the Netherlands.

Still, celebrating European harmony by commemorating the most famous battle in history remained a bit of a paradox – French President Charles de Gaulle allegedly explained his absence from the ceremony by saying he was too busy planning for the 900th anniversary of the Norman invasion of Britain.

On the eve of Waterloo's bicentennial, the tension between national pride and international cooperation remains no less potent.

On June 18th of 2015, members of the British royal family joined high-ranking dignitaries from other European nations and a quarter of a million spectators at a commemorative reenactment that seeks to represent the battle in all its multifaceted and multinational dimensions.

At the same time, however, the Conservative victory in the British parliamentary elections in May reflected a deep ambivalence about Britain's ties with the rest of Europe – an ambivalence that already existed in the wake of Waterloo.

|

| This 1881 painting depicts the British Royal Scots Greys at Waterloo. |

"For Europe," said Britain's Foreign Minister in 1822, "I shall be desirous now and then to read England." This ambivalence animates and helps explain the passion aroused by historians’ debates about the role of other Coalition soldiers at Waterloo. (The liberal Guardian newspaper provocatively suggested Waterloo was really a "German victory" while the Daily Mail dismissed such talk as "mere spoilsports’ mighthavebeen.")

Similarly, France's decision not to send a representative to the June 18th ceremonies demonstrates how potentially divisive Waterloo and the larger Napoleonic legacy remain in France.

|

|

| Present day site of the Battle of Waterloo. |

Many cherished French institutions originated during the Empire, from the Legion of Honor to the civil code (Napoleon’s highly influential law code), and nostalgia for a conquering France in some circles reflects contemporary anxieties about a France in decline. At the same time, Napoleon's establishment of a dictatorship and his reinstitution of slavery stand as deeply unsettling moments of exclusion in the French heritage.

On June 9th, 2015, Belgium issued a commemorative Waterloo coin after all, through a loophole that allows individual nations to unilaterally produce coins of irregular denominations. 70,000 2½ euro coins were minted, bearing the years 1815-2015 and an image of the Waterloo memorial.

The Daily Mail's take on the subject? "French suffer another Waterloo defeat."