On August 25, 1944, Paris was liberated after more than four years of Nazi occupation. Following a week of guerilla combat between Resistance fighters and the occupying German troops, General Philippe Leclerc’s Second Armored Division of the Free French Army rolled through the city on the night of August 24-25, 1944, supported by the U.S. Fourth Infantry Division.

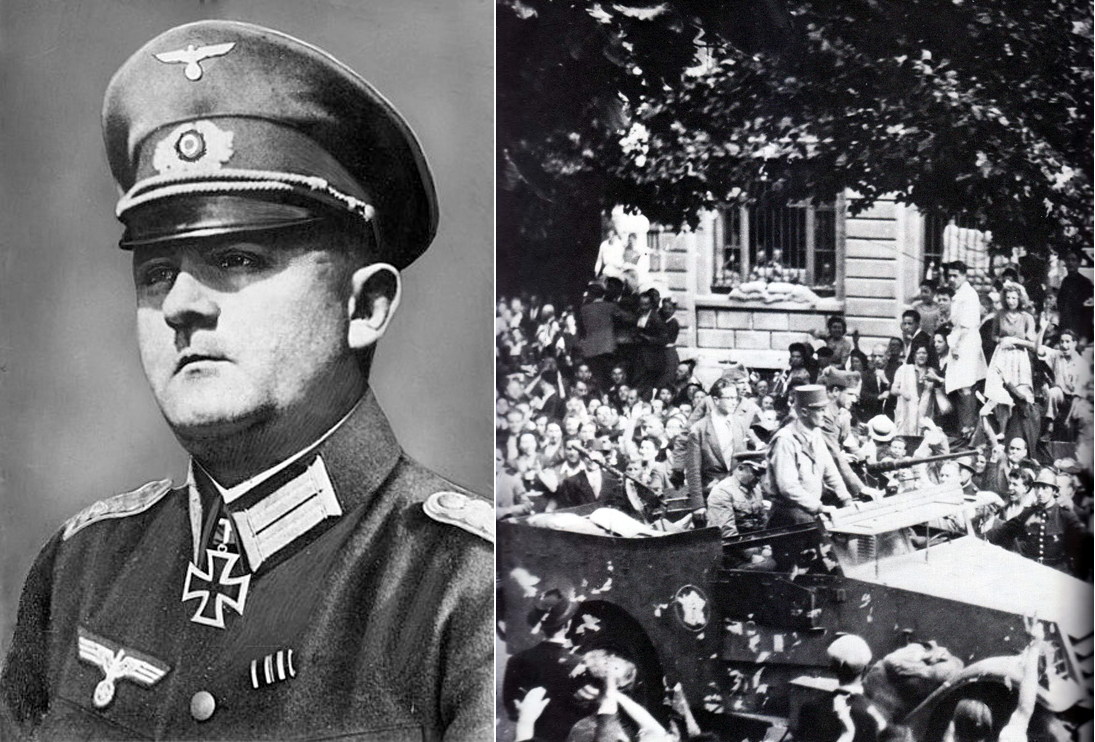

The following morning, General Dietrich von Choltitz, the German military governor and commander of the city’s German garrison, formally surrendered to the Allies. After four years of occupation, humiliation, and the persecution of its most vulnerable citizens, Paris was free.

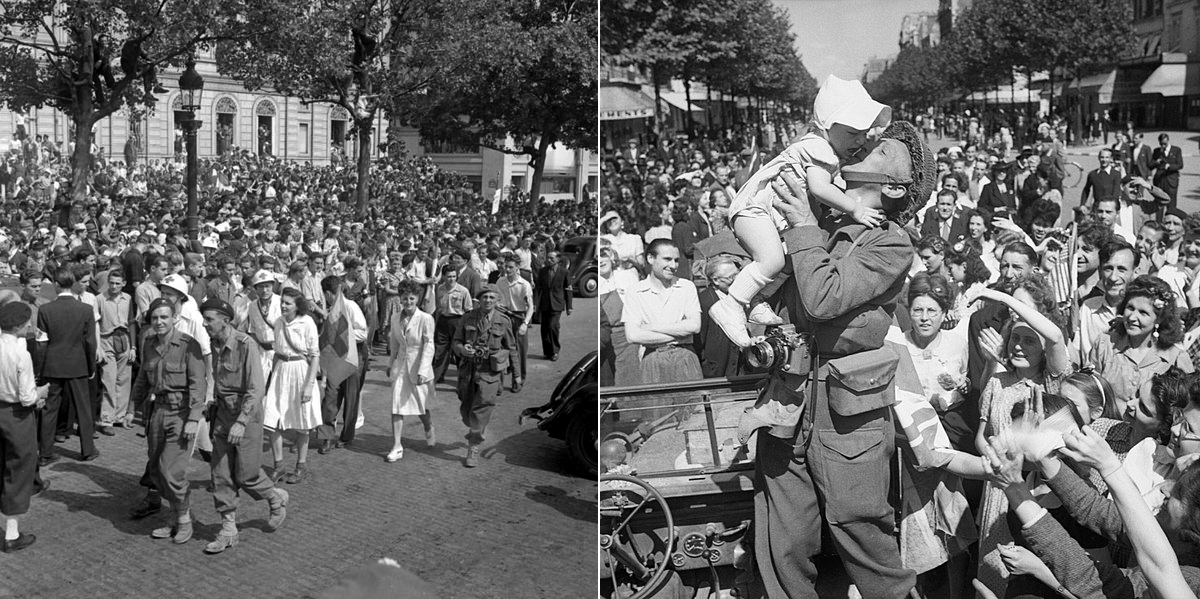

Troops of the French 2nd Armored Division parade down the Champs-Élysées on 26 August 1944.

Contemporary accounts capture the stunned delirium and catharsis that pervaded the city. Jean Guéhenno, a resident of Paris, wrote in his diary:

Friends call me, saying they can see huge fireworks all over the Hôtel de Ville [city hall], with red and blue rockets answering them in the south and west. It was the signal. The first tanks of Leclerc’s army had just rolled up to Notre-Dame. And then all the bells of all the churches rang in the night, drowning out the rumbling of the big guns.

On August 25th, Parisians took to the streets en masse. “I have never seen in any face such joy as radiated from the faces of the people of Paris this morning,” wrote Charles Christian Wertenbaker, Time Magazine’s war correspondent. Six firefighters secretly scaled the Eiffel Tower and hung a homemade French tricolor flag from its antenna. The American writer Ernest Hemingway, a longtime Paris resident embedded with the 4th Infantry, made haste to the Ritz Hotel, where he “liberated” its famous bar and helped himself to several dozen dry martinis.

The residents of Paris throng the streets to greet the arrival of Allied troops after liberation, August 1944 (left); a photographer with the U.S. Army Film and Photographic Unit kisses a small child in Paris, 26 August 1944 (right).

Charles de Gaulle, leader of Free France and president of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, gave a speech at the Hôtel de Ville. “Paris! Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris liberated!” he proclaimed. “Liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the help of all France, of the France that fights, of the only France, of the real France, of the eternal France!”

The following day, de Gaulle led a procession of French troops down the Champs Elysées. A towering figure at six feet, five inches tall, de Gaulle made a ripe target for German sharpshooters, yet he refused to duck as snipers fired on the crowd. Later that day, he displayed similar bravado when shots rang out in the middle of Notre-Dame Cathedral, midway through the recitation of the Te Deum prayer of thanks.

Today, these are all iconic scenes, but the liberation of Paris almost did not happen in the summer of 1944. For U.S. and British military officials at the time, Paris was simply not a high priority. They saw the capture of the French capital as ancillary to the main Allied objective: ending the war in Europe as quickly as possible by compelling the surrender of Germany, in order to pivot their focus to the Pacific Theater and the war against Japan.

After landing on the beaches of Normandy on June 6 in Operation Overlord, the Allies’ advance had stalled for several weeks amid the thick hedgerows of the Norman countryside and dug-in German opposition. Even after their successful breakout from the Normandy beachhead in early August opened the road to Paris, Generals Dwight Eisenhower and Omar Bradley considered Paris an unnecessary detour that would slow the Allied advance towards Germany. They sought to avoid the type of house-to-house urban fighting that had ensnared the Germans at Stalingrad and were leery of having to feed the city’s nearly two million residents.

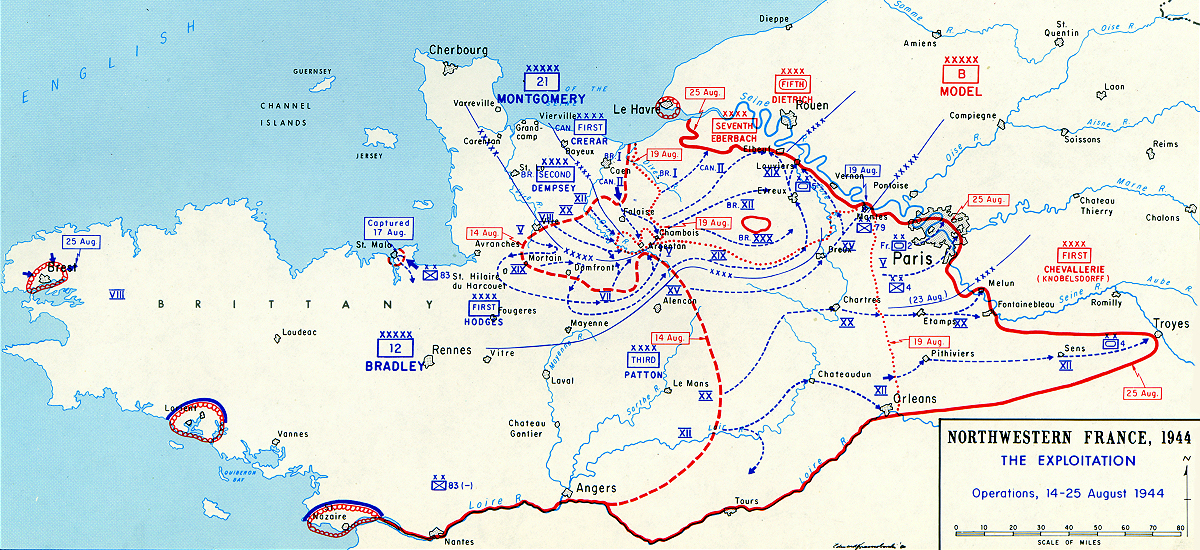

The Allied advance from Normandy to Paris, 14-25 August 1944.

For de Gaulle, however, bypassing Paris was unthinkable. While the city’s value as a military objective was limited, de Gaulle keenly understood its symbolic importance. Whoever liberated France’s capital would gain a huge advantage in determining France’s postwar political fate—and de Gaulle was determined that this advantage fall to the Free French Army, rather than to British or American forces, or another Resistance group.

In the end, events on the ground rendered the debate moot. On August 18th, a general strike broke out across Paris in reaction to news of the Allied advance and two days later, the first barricades went up throughout the city: a telltale sign of Parisian unrest whose origins predate the French Revolution. Resistance units in Paris began to mobilize and clashed with the occupying German troops.

As unenthusiastic as Eisenhower was about diverting the Allied advance, he was also unwilling to stand by and allow German forces to crush the uprising. On August 22nd, he authorized the French 2nd Armored Division to take the city.

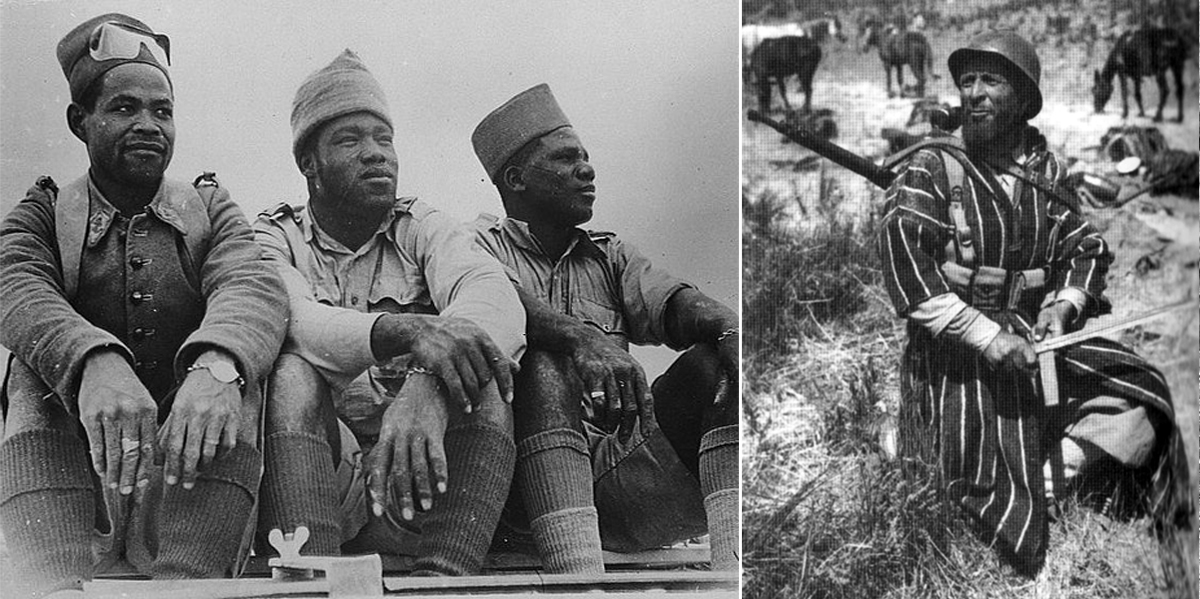

While Allied command agreed to cede the primary role in the liberation of Paris to French troops, the composition of those troops was another matter. As the only French unit to take part in Operation Overlord, the 2nd Armored Division boasted extensive combat experience and an able commanding officer in Leclerc, a de Gaulle loyalist. For American and British officials, however, its greatest asset was demographic: the division had a higher proportion of white soldiers than the Free French Army overall, which was composed largely of soldiers drawn from France’s African colonies.

Three African soldiers in the Free French Foreign Legion, 1942 (left); a Moroccan soldier in the French Army at Monte Cassino, Italy, 1944 (right).

The racial calculus behind the 2nd Armored Division’s selection for the liberation of Paris was quite explicit. In January 1944, Eisenhower's Chief of Staff, Major General Bedell Smith, wrote in a confidential memo: “It is most desirable that the division… consist of white personnel and this would indicate the 2nd Armored division which, with only one fourth native personnel, is the only French division operationally available that could be made 100 percent white.”

A tank of the French 2nd Armored Division in front of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, 26 August 1944.

Contemporary sources fail to explain this insistence on an all-white French unit. But historians have speculated that U.S. officials may have been concerned about how the American public would react to newsreel footage of the liberation of Paris that showed racially integrated troops. The desegregation of the American armed forces would not occur for another four years.

Even when the 2nd Armored Division rolled into Paris, its ranks were not entirely French. Many soldiers were actually Spanish Republicans who had joined the French Resistance after fleeing the fascist regime of Francisco Franco.

The Paris that French and American soldiers found in August 1944 was not the same as it had been before the war. Although spared the physical devastation that befell other major European capitals like London, Berlin, and Warsaw, the occupation upended life in Paris. Four years of strict rationing had drastically reduced Parisians’ food intake, especially those who were too poor to buy additional food on the black market or who did not have relatives in the countryside who could send supplementary parcels. Tuberculosis cases climbed, as did the rates of childhood illnesses and malnutrition. These conditions did not immediately improve after liberation. In March 1945, the average Parisian was still consuming less than 1,400 calories per day.

And then there were those Parisians who did not live to see liberation. At least 40,000 Jews, most of them foreign refugees, were deported east from the Drancy detention camp on the outskirts of Paris to Auschwitz, where the vast majority perished. Hundreds of French Resisters were executed, as well as hundreds more civilian “hostages” in retaliation for acts of sabotage. The Nazis killed more than 1,500 members of the Resistance in the skirmishes during liberation itself.

Parisian Jews being rounded up for transport from the Drancy detention camp, August 1941.

For some, liberation meant a reckoning. The German occupation of Paris had benefited from both the tacit consent of everyday French citizens and the active support of high-ranking French officials and prominent elites like fashion designer Coco Chanel and author Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

During the frenzied, chaotic first days after liberation, impromptu kangaroo courts sprung up to deliver the people's justice. Residents exacted retribution on their neighbors, often in public: women who had slept with German soldiers were humiliated, forced to have their heads shaved and clothes torn. Hundreds of summary executions were carried out across the city.

In most cases, however, separating out the heroes and villains of occupation was far more complicated. De Gaulle’s claim that “all France” had liberated Paris was more patriotic myth than historical fact, an attempt to manufacture unity and restore national pride. The reality of living in an occupied city for four years meant that most people did not fall into the easy binary of collaborator or resister.

Even General von Choltitz defies easy categorization. Military governor of Paris for only three weeks before liberation, Choltitz was a committed Nazi who had overseen the destruction of the cities of Rotterdam and Sevastopol earlier in the war. Even so, when Adolf Hitler ordered him to raze Paris rather than let it fall into Allied hands, Choltitz ignored the command.

General Dietrich von Choltitz, German military governor of Paris, in a May 1940 photo (left); General Philippe Leclerc, 2nd Armored Division (standing, center), transferring Choltitz (seated) to the Gare Montparnasse, where Choltitz signed the surrender of German forces in Paris (right).

Choltitz's motivations have been the subject of debate and speculation for decades. Was he persuaded to spare the city by the entreaties of its prominent residents? Disillusioned with Hitler and the war? Looking to save his own reputation and avoid Allied prosecution for war crimes?

In his memoirs, Choltitz maintained that he had defied Hitler out of love of Paris. In truth, far more pragmatic concerns likely carried the day. Nevertheless, this idea that the City of Light was saved by its own beauty, that it enchanted even the man explicitly charged with destroying it, remains undeniably compelling to all who visit Paris today.