On June 28th, 1969 a belligerent and diverse crowd led an uprising at New York’s Stonewall Inn. The event has become iconic in popular memory as the spark for a new radical lesbian and gay activism. In his Second Inaugural Address, President Barack Obama even linked the event with other marginalized people’s fights for inclusions when he saluted freedom fighters “through Seneca Falls, and Selma, and Stonewall.”

In Stonewall’s wake, a Gay Liberation movement galvanized gay communities nationwide and its anniversary has become a cultural touchstone, as LGBT communities across the country stage Gay Pride events throughout June, displaying queerness in all of its diversity. But while the Stonewall riot indisputably marked a turning point, its history and its legacy are more complicated than the usual celebratory narrative suggests.

The basic contours of what happened are well established.

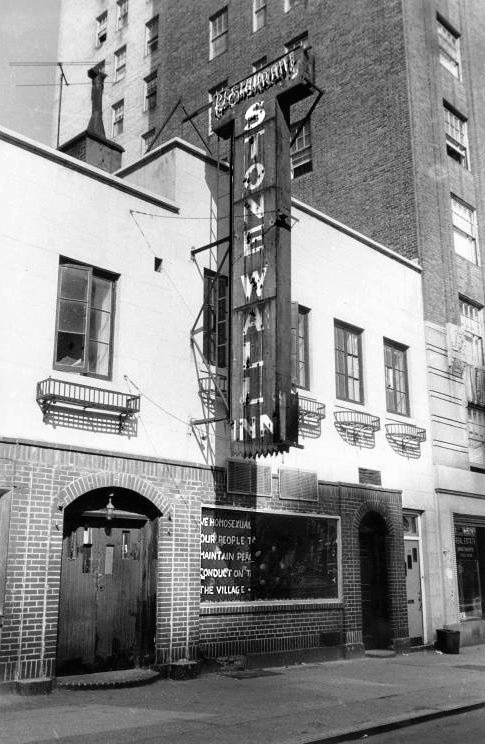

The Stonewall was a seedy gay club in New York’s Greenwich Village—the heart of the gay community. Like many such establishments in the city, it was run by the Mafia and subjected to regular police raids. It was popular with a diverse cross-section of the community, including underage boys as well as transsexuals and drag queens, the latter of whom were vulnerable to arrest for violating state laws against cross-dressing.

As part of an investigation into mob activity, police raided the Stonewall on Tuesday, June 24 and then again in the early morning hours of Saturday, June 28. Although patrons were accustomed to periodic harassment, the second raid turned their mood ugly, and instead of acquiescing to arrest, some of the crossdressers pushed back.

A crowd soon gathered outside, and when the police began aggressively forcing detainees into police wagons, people in the crowd threw rocks and bottles. A full-fledged riot ensued; during which police actually locked themselves inside the Stonewall for their own protection until riot police arrived and cleared the area.

News of the riot spread, and the next night thousands gathered in front of the bar in anticipation of further confrontation. When police arrived to break up the gathering, it instead touched off a second night of rioting.

A reporter for the Village Voice who was present both nights penned a graphic account—reprinted nationally—that characterized the uprising as an unprecedented turning point for the gay community. Thanks in part to the national attention his coverage received, he proved to be right.

The poster for Stonewall (2015).

More often than not, however, this attention has centered on white men as the essential players in the LGBT movement—a tendency that marginalizes other queer people. In particular, some accounts of the uprising erase or minimize the participation of drag queens. The 2015 film Stonewall is the most prominent offender. In the film’s telling, a naïve white teenager from Indiana is the hero of the uprising who touches off the melee by being the first to throw a brick. The 1995 movie of the same name fares somewhat better, as it highlights the presence of women and people of color. However, it, too, features a young white male as its protagonist.

The Stonewall uprising did not happen in a vacuum. Over the prior two decades, gay men and lesbians had faced extreme repression. In what is known as “the Lavender Scare,” the U.S. government purged thousands of men and women from federal jobs in the 1950s and 1960s on suspicion of homosexuality.

During the same decades, courts routinely stripped parental rights from lesbian mothers and gay fathers. And in cities across the country, police departments subjected lesbian and gay establishments—primarily bars—to surveillance and harassment. The raid on the Stonewall Inn was one of many; a regular and unremarkable event to its patrons.

Still, a hesitant gay and lesbian movement was taking shape.

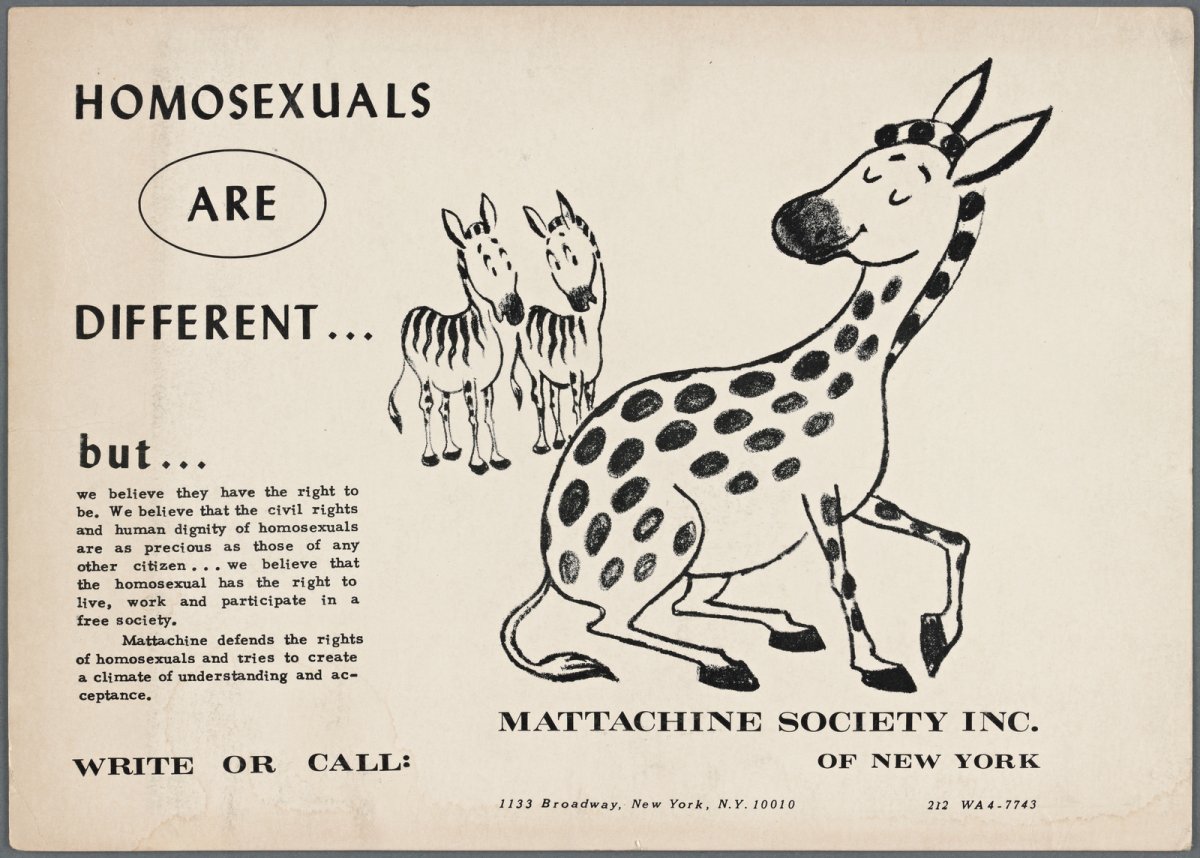

In the mid-1950s, so-called “homophile” groups–the male-focused Mattachine Society and the lesbian organization the Daughters of Bilitis–formed in a handful of major cities. For the most part, the homophiles stressed respectability, and early on they focused more on social activities than on political organizing. As the 1960 progressed, they organized some peaceful pickets, but even then, they aimed to present themselves as not much different from their straight counterparts.

Literature distributed by the Mattachine Society of New York (1951-1975).

By the end of the 1960s, the black freedom struggle and anti-Vietnam War protests, along with an emerging counterculture, had galvanized a new generation of activists fighting for social justice. The new lesbian and gay radicalism was rooted in this milieu.

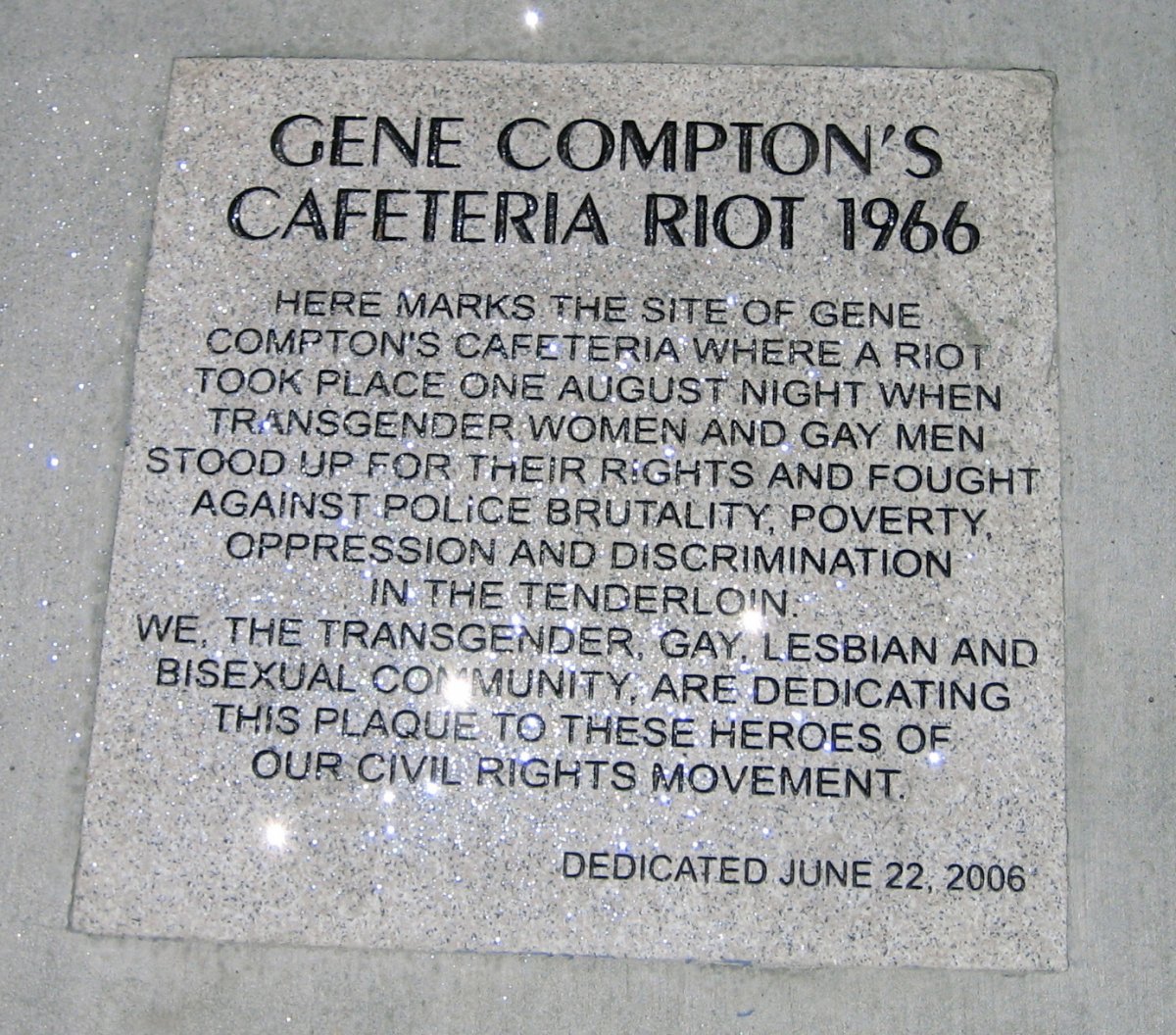

The Stonewall riot was not the first of its kind: patrons of Compton’s Cafeteria—a late night establishment in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district catering to transgender women and drag queens—rose up against a police raid in August 1966. It was Stonewall, though, that ultimately triggered a revolution.

Monument to the LGBTQ participants of the Compton Cafeteria Riot.

In the riot’s immediate aftermath, a group of young activists in New York organized the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), which staged public protests and emphasized coming out of the closet as a transformative act, both because it made gay people publicly visible and because it allowed them to express their authentic selves. GLF activists demanded an end to police violence and fought against the stigma attached to homosexuals (a noteworthy result of which was the American Psychological Association declassifying homosexuality as a mental illness in 1973).

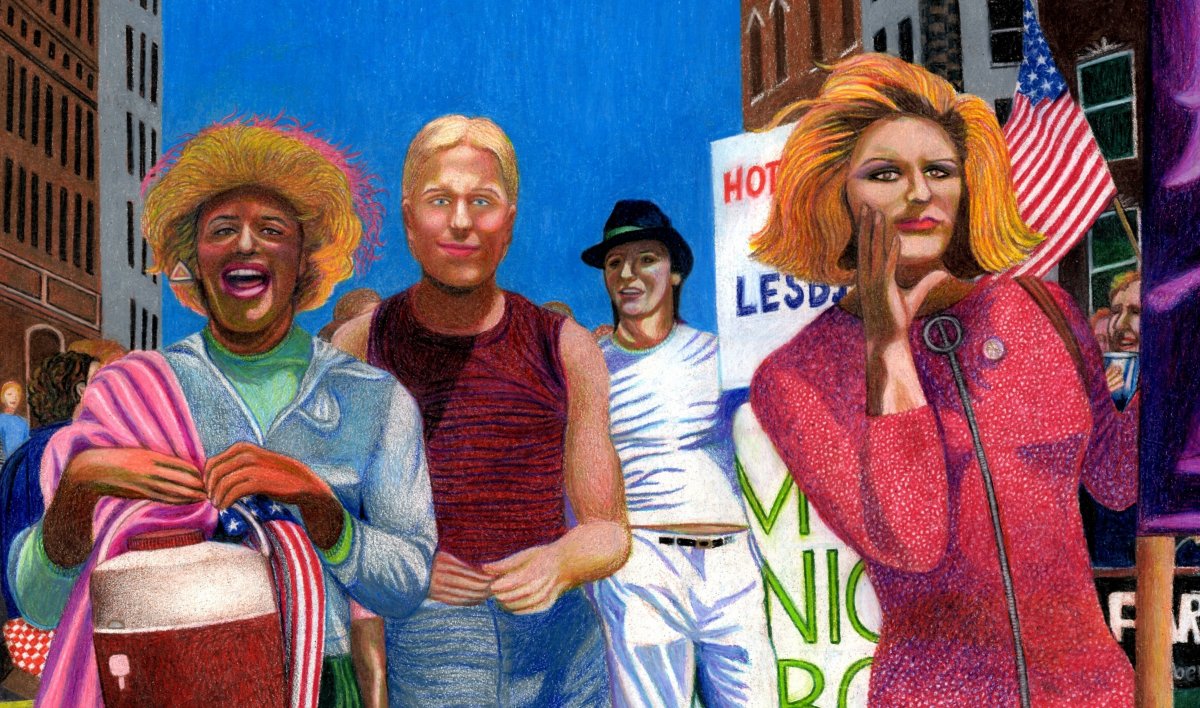

Stonewall served as a rallying cry, and inspired Gay Pride marches in several cities on the first anniversary of the uprising. And in marked contrast to the homophiles, gay liberation’s scope was broad: chapters sprung up in both large and small cities across the country, as well as on a number of college campuses.

By the mid-1970s, gay male activists in the nation’s biggest cities largely shifted their focus to a fight for political inclusion, while many lesbians embedded their activism within feminist organizing circles.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s produced a more somber kind of activism centered on health care along with demands for accelerated research and government aid. The urgency of the epidemic also precipitated a return to confrontational tactics, primarily on the part of the upstart AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), whose rallying cry was “Silence Equals Death.”

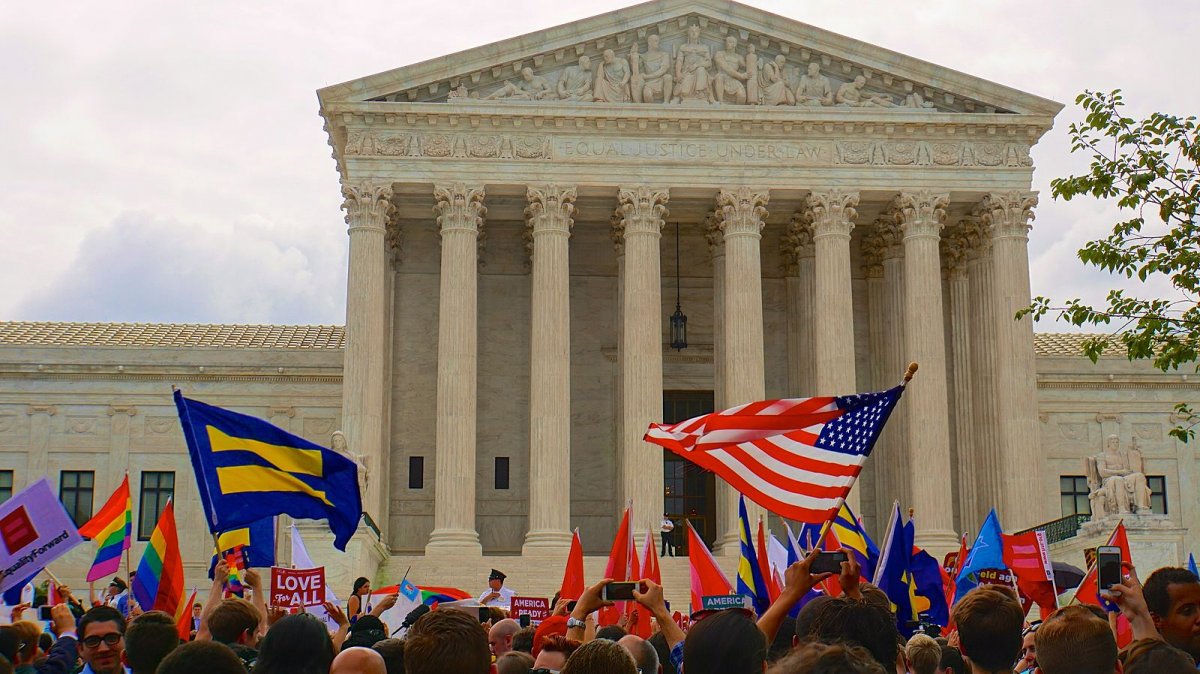

As the twenty-first century dawned, the focal point of queer activism shifted once again. In a return to the politics of inclusion, LGBT organizations embarked on a concerted and ultimately successful campaign to gain legal recognition of same-sex marriage, something once unimaginable to even the most radical gay liberationists.

Yet despite the remarkable gains the LGBT movement has made, the current moment is fraught. The Trump Administration has championed so-called “religious freedom” laws as well as laws limiting transgender rights. In addition, just in recent weeks, the Supreme Court agreed to take up a series of cases that will decide whether the Civil Rights Act’s protections apply to sexual orientation.

Even after more than half a century, the Stonewall Uprising underscores both the diversity of LGBT activism and the continued urgency of fighting for freedoms. Only when there is justice for all of the heroes of Stonewall will President Obama’s stirring words fully ring true.