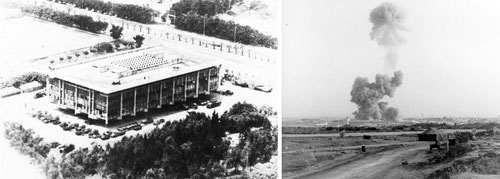

At 6:22 a.m., October 23, 1983, a massive explosion ripped through the barracks of the battalion landing team (BLT) of the 24th Marine Amphibious Unit at the Beirut International Airport.

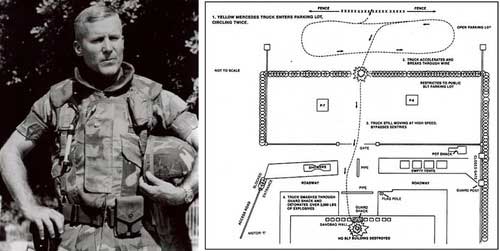

Originating from a truck that had rammed through the marines’ perimeter, the detonation struck with the force of 21,000 pounds of TNT. 240 U.S. servicemen and one Lebanese custodian were killed in the attack. It was the greatest single-day loss of life for the Marine Corps since the first day of the Battle of Iwo Jima in February 1945.

A short time later, a second explosion at a French barracks in Beirut killed 58 French paratroopers.

The deadly attacks happened 30 years ago this month; from then until now, U.S. policy has continued to struggle to find a clear, consistent policy to achieve stability in the Middle East in the face of complex, multi-faceted challenges. With atrocities now piling up in Syria, and the question of U.S. intervention hovering, the events leading up to the 1983 barracks bombings remind us of the difficulties of finding a way to quickly and cleanly intervene in the Middle East.

The American and French forces were serving in Beirut as part of a multinational peace-keeping force. Sectarian political and religious groups had clashed in Lebanon for years.

Founded after World War I under French control, Lebanon included Maronite Christians and Muslims (divided between Sunnis, Shi’ites, and Druze). The Maronites held the majority by a thin margin at that time. The Muslims, however, tended to want to be a part of Syria, currently also coalescing under French rule.

Following independence from France in 1943, the Muslim factions agreed to maintain a unified Lebanese state, the Maronites agreed to accept the essentially Arab nature of Lebanon, and the “National Pact” was established. The sides agreed that a Maronite would be president, a Sunni prime minister, and a Shi’ite speaker of the Parliament. A ratio of 6.5 to 1 Maronites to Muslims would be maintained in Parliament.

By 1958, cracks developed in the Pact, as President Camille Chamoun attempted to change the constitution to exceed his limit of one term; the resulting chaos led to the first U.S. Marine intervention there.

By the 1970s, although demographic changes had made the Maronites only a third of the population while the Shi’a became the majority, the Maronites opposed Shi’a demands for political reform to reflect this reality. Several Maronite leaders, most notably Pierre Gemayel, formed militias to protect the status quo.

To make matters worse, the Palestinian Liberation Organization used Beirut as its main base after being expelled from Jordan. Welcomed by Lebanon’s Muslims, the Maronites objected to their presence. When violence broke out in 1975 after an unidentified gunman killed several Maronite militia members, an escalating series of reprisals led to all-out civil war.

At the height of the violence, as many as twenty-five distinct armed groups divided by religion and political ideology fought with one another as the Lebanese government collapsed under the strain of the violence. Lebanon was also occupied by foreign powers seeking to support their proxies and maintain their position in the fragile Middle Eastern power system. Syria occupied the Bekaa valley in eastern Lebanon in 1976, ostensibly to stabilize the civil war; Israeli invaded in June 1982, in order to finally dislodge the PLO from its base of support amongst the Palestinian refugee population.

Following the Israeli incursion, the multinational peacekeepers were deployed in an attempt to restore stability. Early indications that the peacekeepers’ presence led to greater stability were promising. Thomas Friedman, then based in Beirut as a reporter for The New York Times, reported that some civilians were actually beginning to replace their shattered windows, a sure sign of hope.

By September 1982, international forces had withdrawn. However, a subsequent massacre of Palestinians, largely non-combatants, by a Maronite militia led to the redeployment of the peacekeepers in an open-ended stabilization mission.

The peacekeepers’ mission was to project a sense of stability but not to actually engage in combat operations. Meanwhile, while a combined U.S. Army/Marine unit trained the nucleus of a national Lebanese army. U.S. long-term plans remained only partially formed and reactive to events on the ground. The U.S. settled on supporting the government of Maronite Amin Gemayel, largely because Gemayel won Israel’s support by opposing the Palestinians.

Rather than act as the national leader Washington hoped for, Gemayel continued to act as a factional leader. He pursued the interests of the Maronite minority over those of the other sectarian communities and the country as a whole. Now, however, he was as a factional leader with the support of a powerful friend.

Despite some initial optimism in the United States and Lebanon, the situation began to deteriorate. Violence was increasingly targeted at the U.S. presence.

In April 1983, a truck bomb exploded outside the U.S. Embassy in Beirut. Dozens were killed, including several key members of the CIA station, hampering effective intelligence activities for months to come. Sporadic attacks followed, killing several Marines, and wounding dozens.

When Col. Timothy Geraghty took command of the Marines on May 30, 1983, however, he was still given to understand his mission was not primarily a combat one. Marines in the guard stations around their increasingly insecure base at the Beirut International Airport kept their weapons unloaded unless a direct threat presented itself. As the main threat to the Marines at the airport was random attacks from rockets, artillery, and small arms, Geraghty increased the number of marines billeted in a fortified building that became the home of the Marine Battalion Landing Team, the main combat unit of 24th Marine Amphibious Unit.

Increasingly identified by the various factions in Beirut as aligning with Gemayel’s faction, the peacekeeping forces remained officially neutral.

However, in September, during particularly heavy fighting between the American-trained Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) and various militia groups, U.S. Ambassador Robert McFarland requested that the U.S. provide direct air and naval support to the LAF.

Geraghty, with the support of senior Army and Naval officers, blocked these requests, fearing they would be tantamount to a renunciation of U.S. neutrality. Reflecting later on the repeated calls for intervention against the Shi’a militias, Geraghty reported that he “wondered if anyone else realized where this f——— train was headed.” The strikes were eventually carried out over his objections.

While there can be no direct link drawn between the decision to directly aid the LAF and the October 23 bombing, it is clear that the by the time of the bombing the Marines’ situation was substantially changed from its original parameters. While their basic stated purpose was neutral peacekeeping, specific plans for a long-term settlement remained elusive.

The Marines also faced the danger of militia groups supported by Syria and Iran. The president of Syria, Hafez al-Assad, wanted to establish Lebanon as a buffer between Syria and Israel. Iran wanted to export its Islamic revolutionary movement.

Though officially it was a group called “Islamic Jihad” that carried out the attack on the Marine Barracks, elements of Hizbāllah were deeply involved. Rather than a secular, Arab nationalist group like the PLO, Hizbāllah (“The Party of God”) was a pro-Iranian Islamist organization that accepted the Iranian call for warfare against the West in general and Israel and the United States in particular.

Recently declassified material has shown that on September 26, 1983, the NSA intercepted an Iranian message to their ambassador in Damascus, directing him to “take spectacular action against the American Marines.” That intercept was not passed along to Col. Geraghty, who after the attack was reprimanded for concentrating his men so closely and not taking steps to prevent the truck bomb, though such a massive bomb had been unprecedented.

The bombing led to the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Beirut early in 1984. President Reagan did not want to have to fight Congress for a further commitment. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger had opposed the intervention from the start.

The fallout of the Marine intervention was the direct cause of Weinberger and General Colin Powell cooperating to develop what would eventually be referred to as the Powell Doctrine. Also deeply influenced by the American experience in Vietnam, the doctrine called for the commitment of U.S. troops only in cases of vital national interest, assured public support, and clearly defined and attainable goals.

In the thirty years since the bombing, U.S. policy has struggled to find clear objectives and the means of obtaining them in the Middle East. The diffuse, unpredictable terrorist organizations like Hizbāllah came to overshadow earlier, secular groups like the PLO. Following the Marine withdrawal, an emboldened Hizbāllah continued to act aggressively in the region. Geraghty, among others, later argued that a failure to retaliate against Hizbāllah only further emboldened the movement.

The sectarian divisions that the peacekeepers sought to transcend in Beirut but which ultimately engulfed them remain a fact of life in many conflicts throughout the Middle East and the world. Such is the case currently in Syria, in which an Alawite government, supported by a predominately Shi’a government in Iran and by other minority groups in Syria, faces a diverse opposition from the majority Sunni population that includes some groups affiliated with al Qaeda.

In calling for intervention in Syria to punish Hafez al-Assad’s son, Bashar, for using chemical weapons against his opponents, President Obama struggled to define his actual objectives. Though halted for the moment after Assad agreed to destroy his chemical weapons stocks, the situation remains terribly unstable.

Whatever the outcome of the current crisis in Syria, the tragedy in Beirut should serve as a stark reminder of the complex, unexpected, and dangerous results that can stem from open-ended and poorly defined intervention in the Middle East.