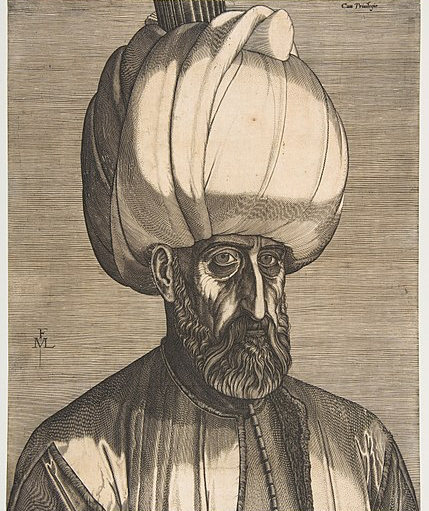

Süleyman, who would be known to the west as “the Magnificent,” began his reign as sultan of the Ottoman Empire in September 1520.

His political career began far earlier: as a teenager, he served as a provincial governor and was key participant in his father Selim’s (r.1512-1520) rebellion that secured him — and Süleyman, by extension — the throne. Süleyman’s reign lasted 46 years, the longest in Ottoman history. Over that span, he rose to be one of the most powerful and influential monarchs of European history, feared on the battlefield and the conqueror of new lands for his empire.

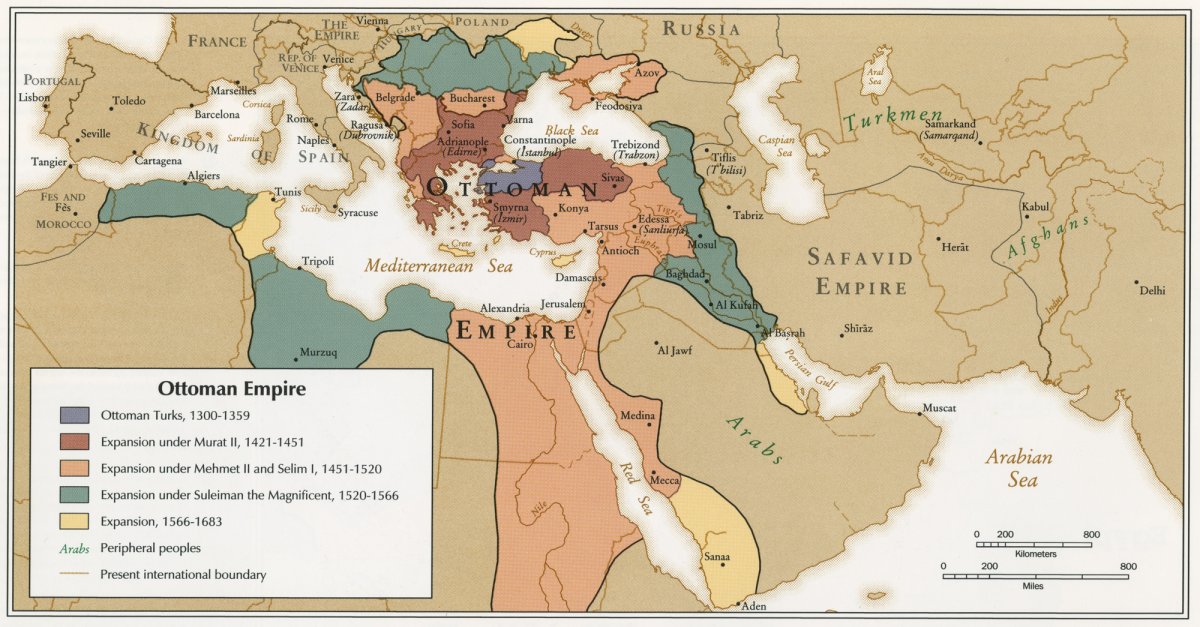

When Süleyman was made sultan, his kingdom encompassed the peoples and territories of the Balkans, Anatolia, the Levant, and Egypt. Under his reign, it expanded to include much of North Africa, Hungary, and Mesopotamia.

In the first six years, Süleyman took Belgrade and Rhodes. In 1526, he also scored a decisive victory against the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies at the Battle of Mohács, during which Hungary's King Louis the Second (r.1516-1526) lost his life. His death sparked a succession crisis and border dispute among Habsburg Austria, the Ottomans, and the kingdoms of Croatia and Hungary, allowing the bulk of Hungary to come under Ottoman rule. Years later, Süleyman himself died “peacefully” in his command tent while leading his last campaign against Szigetvár, Hungary in 1566.

A map showing the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, with conquests by Süleyman indicated in green.

His was a multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic, and multi-confessional empire. The Ottoman state had little interest in radically changing the attitudes or practices of local groups if they were peaceful. Consequently, Ottoman governance was often curtailed by local custom. It was expected that Ottoman officials would have a knowledge of local practices and norms, which they were not to tread upon lest it cause unrest.

The Ottoman world was one in which Islam was privileged and Süleyman’s reign marked a renewed interest in Islamic religious matters. Nonetheless, all groups of the empire found niches to fill and were generally allowed to maintain their way of life and flourish during his reign.

Süleyman played a pivotal role in European affairs during his 46 years in power. He pledged assistance to Protestant causes (to undermine the Habsburgs and others) and did not hinder Protestantism taking root in Hungary or Transylvania. He formed an alliance with the French against the Habsburgs and transformed much of the Mediterranean Sea into an “Ottoman lake” for decades to come. The effects of Süleyman's reign continue to be visible in modern-day Europe.

In the Islamic world, Süleyman extended the claim his father had tentatively made to the Caliphate and Universal Rule. Henceforth, all Ottoman sultans saw themselves as Caliph and “head” of all Sunni Muslims. Süleyman’s claim further cemented differences between Shi’a and Sunni institutions, as the Shi’a Safavids (centered in Persia) and the Sunni Ottomans sought to legitimize their rule and affirm their claims against each other. This struggle intensified confessional concerns and the differentiation of the two sects and empires.

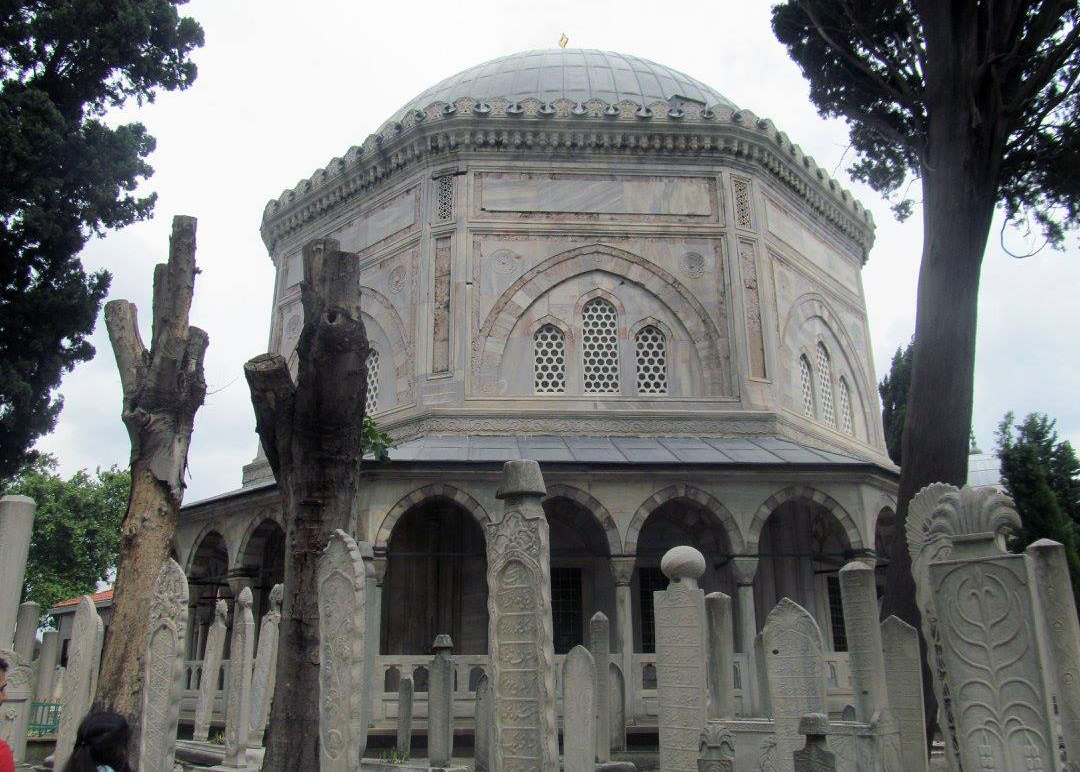

A poet and goldsmith himself, Süleyman was a major patron of the arts, whose cultural legacy endures to this day. His mosque, seen here, is the second largest of the Ottoman era in the city of Istanbul. [Photo by author]

Beyond the military conquest for which he has been remembered, Süleyman also “standardized” Sultanic law. He collected and edited the various law books of his forbearers and added a number of statutes to create a more universally applicable singular text. This law book, like its predecessors, provided the basis for punishments for various offenses, favoring cash payments based on the perpetrator’s social status for most crimes.

His work codifying laws earned the Sultan his Ottoman honorific “Kanunī,” or “law giver.” He is still remembered globally as Kanunī, a status that earned Süleyman a bas-relief in the U.S. Capitol Building as one of the world's great lawmakers.

For all the cultural splendor and military success of Süleyman's rule, it was also tragic in an almost Shakespearean sense. His marriage to Hurrem Sultan (Roxalana) (d.1558) caused a great deal of controversy because Süleyman was the first Sultan since the early years of the empire to marry. Süleyman was deeply devoted to his wife: several of his poems are directed to her and she accrued remarkable power in her own right.

This marriage supposedly caused no small amount of gossip. There were claims that she was a witch that had beguiled the Sultan and she was the excuse behind many of the intrigues that Süleyman dealt with in his long reign.

Indeed, political intrigue followed him over the course of his rule. He was forced to have his dear friend and one of his longest serving grand viziers, Ibrahim (d.1536), killed because he took too many royal prerogatives for himself. Likewise, he had his politically popular son Mustafa (d.1556) executed and participated in a minor dispute against his son Beyzid (d.1561), who was also strangled to death at his father's order.

Süleyman’s rule has long marked a turning point in Ottoman history as well as that of the regions the empire controlled. It was under his reign that Ottoman institutions reach the supposed peak of their classical form, a largely hermetic system staffed by individuals trained internally rather than accessible to outsiders.

Many historians have argued that Süleyman represented the apogee of Ottoman power and statecraft and his death started a centuries-long decline. We now know this story of decline to be false, though the Süleymanic period did give way to a moment of temporary crisis and reform in the seventeenth century.

It is arguably under Süleyman that the Ottomans began to feel the weight of their success. They largely reached the limitations of their supply lines and infrastructure, leading to a greater focus on internal affairs rather than a pressing need for territorial expansion. Although later Sultans did conquer more territory, they often found wars to be rather prolonged affairs with multiple fronts and little gain.

The system of centralized rule that “finalized” under Süleyman had to adapt in short order to the rapidly changing world and the various crises that rocked Europe during the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The empire began a controlled decentralization in response to the need for tax in kind, changes in the nature of warfare, the Little Ice Age, and other transformations in Europe. It was this adaptability—rather than clinging to raw power—that allowed the Ottoman Empire to weather these crises.

Süleyman, despite his authority, recognized this need for flexibility. His greatness and the empire's success were predicated on this mixture of “tolerance,” power, and innovation. Where so many other empires and kingdoms collapsed, the Ottomans survived into twentieth century.

Remembering the reign of Süleyman stirs up different feelings: some seek to claim prestige in the Ottoman past and others seek to revile it. Yet, it behooves us to reflect on Ottoman rule and the “Magnificent” at our current juncture.

Süleyman's tomb, which contains the remains of the Sultan and several of his descendants, is still a popular destination for Istanbul residents and visitors today. [Photo by author]

The Sultan often reflected in his poetry on the transitory nature of rule, life, and power. His poetry characterizes the world as a trap, filled largely with misery. Given the events of his long reign, he likely felt keenly the repercussions of rule. Despite the pains power caused him, he knew that nothing, including his own reign, lasts forever.

Want to Learn More?

Uriel Heyd's Studies in Old Ottoman Criminal Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973) contains an English translation of Süleyman’s law code, in addition to an analysis of it. Leslie Peirce's Imperial Harem (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993) discusses not only Süleyman’s wife but also the politics of the Ottoman royal household in general up through the seventeenth century. Tijana Krstić's Contested Conversions to Islam (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011) gives a good overview of "confessionalization" in the Ottoman empire of the sixteenth century and beyond. Finally, see The Turkish Letters, by Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (London: Eland, 2005). Busbecq, the Habsburg ambassador in 1554, and 1556, remarks not only on the culture of Constantinople, but on the political happenings of the period, including the conflict between Süleyman's sons.