February 26, 1885, was an unremarkable day in the Congo basin, where it passed like many others. Yet thousands of miles away in Berlin, the General Act of the Berlin Conference on West Africa was signed.

The conference has become known for “carving up the African continent” for the benefit of European colonial powers, although the only boundaries that were agreed upon at the conference were those of Congo. Much of the document is concerned with guaranteeing free trade in central Africa and the free navigation of the Congo and Niger rivers.

Rather than a defining moment or a milestone, the Berlin Conference was emblematic of an era. Its dry, legal language hides a violent history and was the translation of a frenzied fever dream.

Increasing numbers of Africans were confronted with a new reality in the late 19th century: the efforts of Europeans to make inroads into their lands to rule, possess, “civilize,” and extract resources.

The meeting in Berlin was an effort by the European powers to stay out of each other’s hair while they did so. It imagined full domination rather than reflecting reality on the ground. As such, the conference did not formalize the partition of Africa so much as help enable the process in a way that managed competitive European colonial desires.

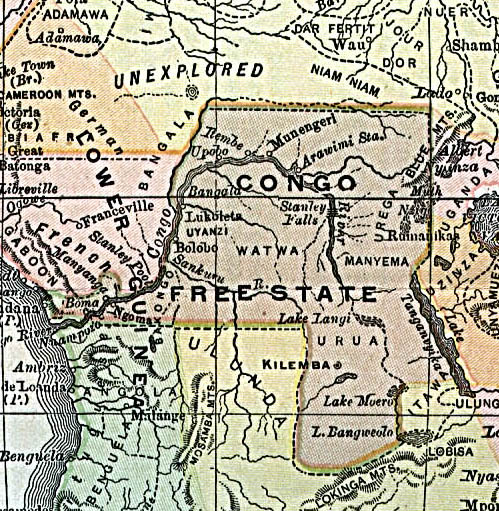

The colonial presence on the ground was scarce in 1885 and much of central Africa was in fact still unknown at the time of the Berlin conference.

The International Association of the Congo (IAC) was a vehicle for Leopold II, the second king in the young Belgian monarchy, and his entourage to explore and gain footholds the region under the guise of scientific exploration.

It had outposts that were long distances apart, as were the few missionary posts, mostly occupied by British and American missionaries. On June 1, 1885, the IAC was transformed into the Congo Free State (CFS), ruled and owned by the Belgian king.

With ambitions that far outmeasured his small kingdom, he had his sights set on lifting the profile and economic might of Belgium and its elite, as well as his own.

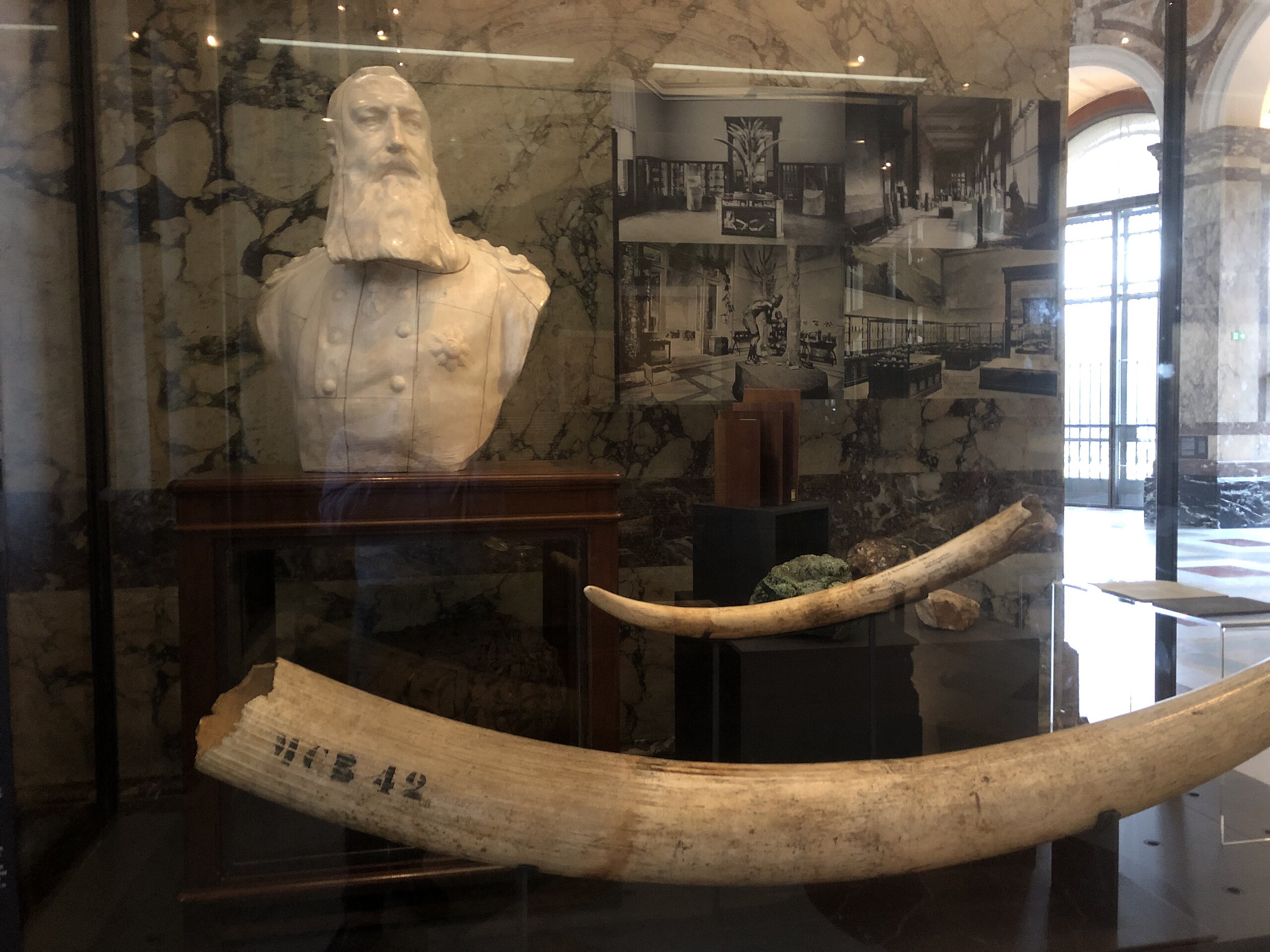

The initial economic draw of the region had more to do with the lucrative ivory trade. The latter followed the same pathways from the interior and often included the same African intermediary trading communities as the trade in enslaved people, a previous “resource” for the global economy.

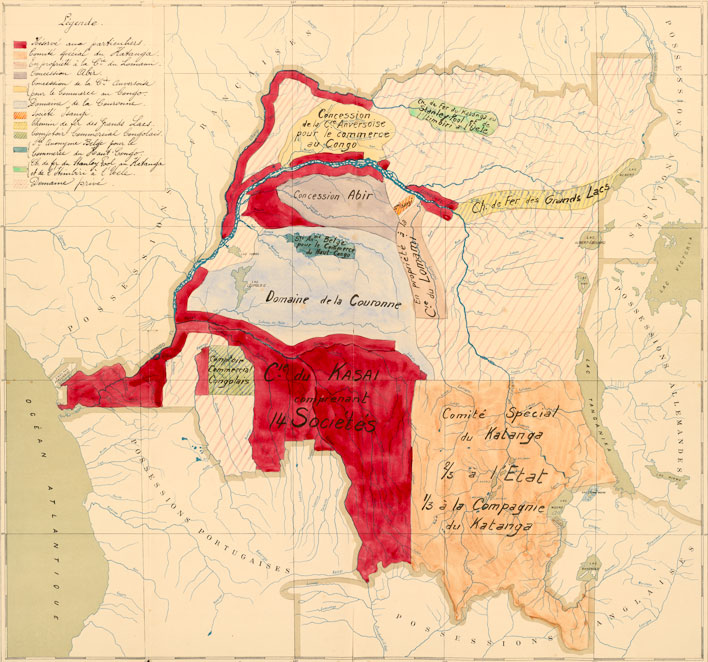

After some years, Leopold II turned to concessionary companies to make the exploitation of the region cheaper.

These companies led to mass atrocities, especially in the context of rubber collection. It also diminished the role left to play for African traders in global trade networks. Although the timing and intensity of the experience of colonial conquest varied across the Congo basin, the atrocities of rubber exploitation in particular, have come to stand for the impact of colonialism on the continent writ large.

Such exploitation was rendered possible because of the deeply racist and dehumanizing lens through which African peoples were regarded. This view became embedded in science as well as in moral and religious thinking.

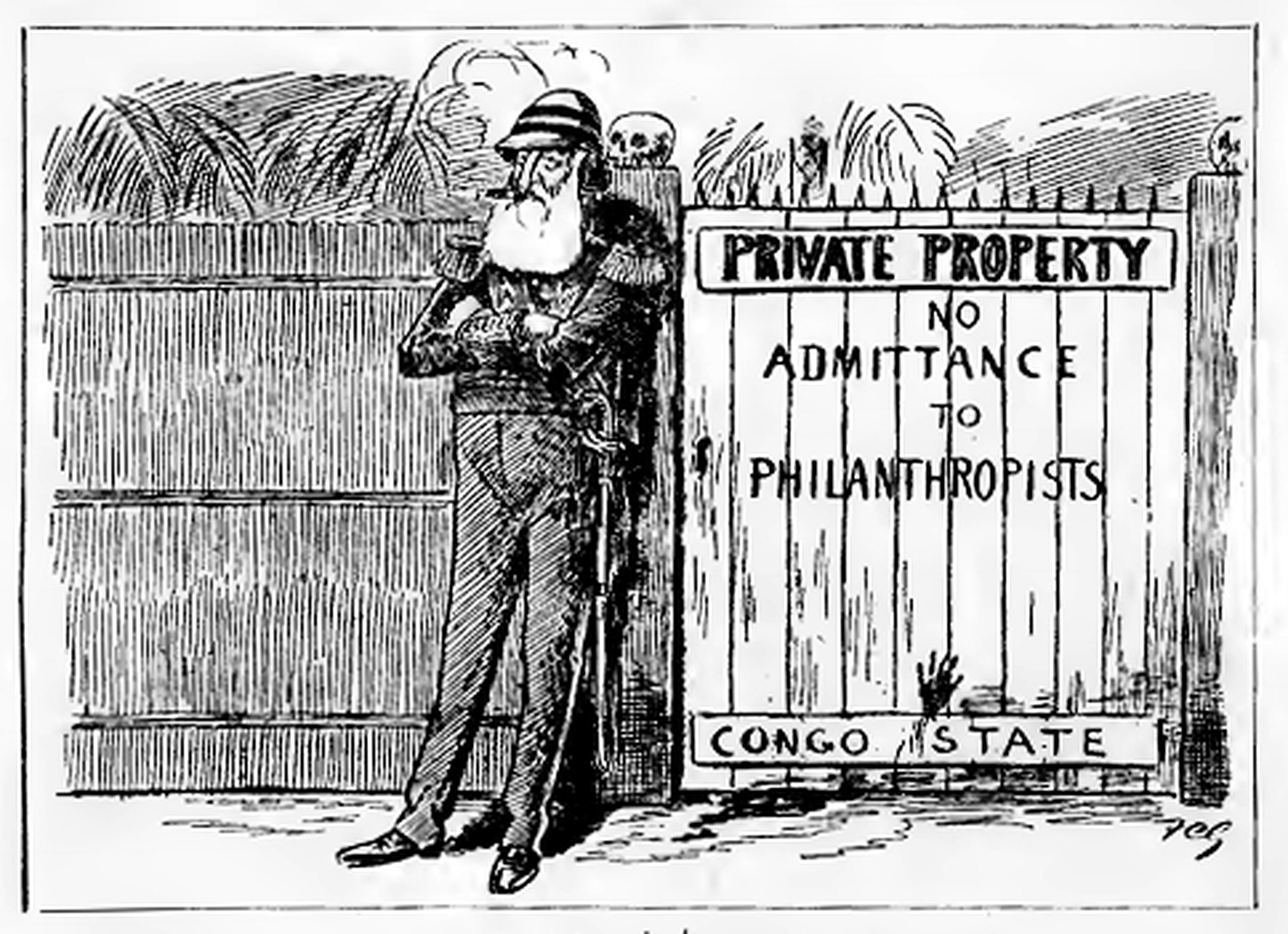

Although initially the IAC and CFS officials relied on alliances with African rulers, as the colonial state gained ground and wanted to increase its monopoly over trade (contrary to the spirit of free trade established by the Berlin conference), it fought many of these rulers. Arab Swahili traders specifically were targeted under the guise of a humanitarian campaign against slavery.

Given the small number of white colonials, the Congo Free State as well as its concessionary companies relied on a colonial army to impose rule. White officers directed African soldiers. Often “freed” from slavery or “orphaned,” many of these young men passed from one master to another. Ironically, the propaganda image of Leopold II as an anti-slavery crusader exists to this day.

The African History of the Berlin Conference?

How we mark the Berlin Conference depends a great deal on our point of view. Do we prioritize a diplomatic event instead of a violent one? An international rather than an African one? Does it move the historical focus to the role of the European, Russian, American, and Ottoman diplomats rather than the Africans who had to live with the consequences?

How did Congolese tell this history?

Although African voices are scarce in the archival record, there are a couple of places where we can find them. For example, they are in the records of testimonies against the rubber abuses, recorded by British and Belgian commissions of inquiry.

These were, of course, aimed at documenting abuses, but the voices that come through illustrate how deeply violence—and the constant threat of violence—in all its forms penetrated communities.

Punitive expeditions, forced labor, mutilations, and torture culminated in mass atrocities that decimated communities and damaged them for generations. People resisted such an onslaught: by fleeing or hiding from soldiers, or by attacking colonial posts, for example by setting them on fire. Resistance, however, often resulted in more violence.

“…the whitemen have come to this country to steal everything they want from the people, and if they object they will be killed.... They are afraid to complain to the Government whitemen when the soldiers rob them because they would not be believed – and also because they do not trust or believe in the Government whitemen themselves.”

—Frank Teva Clark, 1903

The population of the Congo saw clearly the resource fever and dehumanization driving the violence and conquest. The latter is clear from a series of essays, written in 1953 by students and teachers on mission posts in the Equator region. Even though the writers were young men, they put to paper the stories passed down in their own communities.

“When we were among ourselves, the [agent of the] SAB arrived and told us: ‘the goal of my voyage is trade.’ …. We hastily prepared for war and asked them: ‘what have you come to do here?’ And they answered: “We sell things, but what do you want?” … Later, they fought the Elinga people.… In less than a month, we were surprised by a war that decimated us without mercy.”

—Petelo Wenga, student, 1953

Jospeh Iloko, another student, tells what happened after the war of conquest:

“‘Now [the white man said], we will make peace and you will collect rubber for us’ […] And when people did not bring enough [rubber], they killed them, as in war.”

—Jospeh Iloko, student, 1953

Jean Boenga, an assistant teacher, described what he witnessed when other Congolese tried to buy up rubber to insert themselves into the trade as intermediaries:

“With regard to those intermediaries, the riflemen stopped [those] who came to buy rubber. They killed many among [them]. The corpses were strewn about the earth like treetrunks. Everyone fled into the forest.”

—Jean Boenga, assistant teacher, 1953

Legacies of 1885

The 1885 Berlin conference was a diplomatic event that testified to European ambitions for the region. It has become symbolic of an era of violence and exploitation, the long-term consequences of which are still felt today. The (rough) contours of the current-day Democratic Republic of Congo can be traced back to those of the Leopoldian Congo Free State.

Although political independence was achieved by Congo in 1960, patterns of exploitation and authoritarianism were not easily dismantled. The desired resources have shifted over time, from ivory and rubber to copper, gold, diamonds, and coltan, among others. They continue to fuel a global economy.

Yet the patterns of exploitation remain those based on extraction, intertwined with authoritarian regimes and violence perpetrated against the region’s population.

![]()

Learn More:

Frank Teva Clarck’s testimony was drawn from Robert Burroughs, African Testimony in the Movement for Congo Reform: The Burden of Proof. Routledge, London, 2018.

The 1953 essays can be found in the journal Annales Aequatoria, 1995 and 1996 (in French).

Robert Harms, Land of Tears. The Exploration and Exploitation of Equatorial Africa. Basic Books, New York, 2019.

Chérie N. Rivers, To Be Nsala’s Daughter. Decomposing the Colonial Gaze. Duke University Press. 2023.

Osumaka Likaka, Naming Colonialism. History and Collective Memory in the Congo, 1870-1960. University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.