India is now suffering a massive second wave of COVID-19 and the crisis is spilling into neighboring countries. As Indian case counts exceed 400,000 daily and the healthcare system reaches its breaking point, patients are left scrambling to find oxygen, medication, and hospital beds. The official daily death toll now nears 4,000, and this is likely a significant undercount.

Health checks in India designed to curb the spread of COVID-19, 2020.

There are plenty of immediate reasons for this heartbreaking tragedy, and chief among them is a failure of governance: a failure by the Indian government to prepare for a second wave, to act rapidly as cases rose, and to ensure patients’ access to lifesaving medical assistance, all compounded by the emergence of a new variant that may be more transmissible.

Alongside these immediate reasons, there is also a longer history that helps explain why India was so vulnerable to COVID-19 and to the tragic collapse of its healthcare system.

That history, stretching back to the nineteenth century, reveals a chronic lack of investment in public health measures and a disregard for the health of ordinary Indians. Even at this eleventh hour, there is much that can be done to control the pandemic in India and care for those who are ill. But understanding this longer history is essential to tackle the deeper roots of crisis and to challenge the underlying health inequities that have become so glaringly apparent in India’s second coronavirus wave.

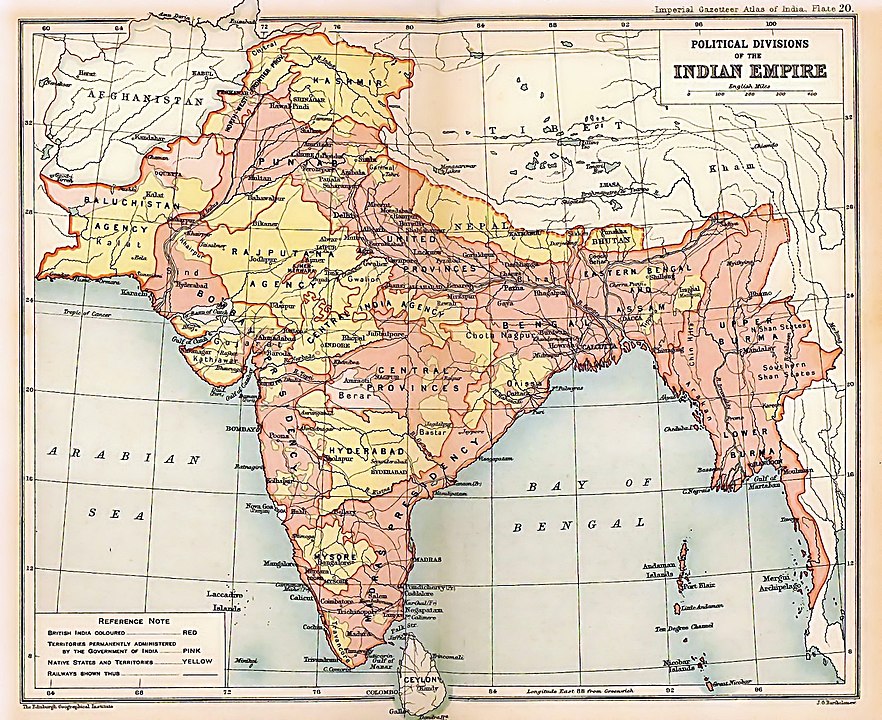

The modern history of Indian public health begins in the nineteenth century, when the British imperial government ruled over a sprawling colony that encompassed modern day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. British administrators feared the prospect of epidemic disease breaking out in the military, the cornerstone of imperial control. They were also concerned to protect the well-being of European civilians in India.

A 1909 map of the British Indian Empire.

For these reasons, early public health initiatives, which consisted mostly of environmental measures such as sanitation, focused on military cantonments and on European civilian enclaves. Initiatives geared to the Indian population overall were severely limited in their ambition and hampered by a lack of funds.

Historians debate whether these limitations were due primarily to the imperial administration’s stingy approach to funding health and welfare, or to Indian resistance to regulations issued by a foreign government, which were sometimes at odds with indigenous understandings of disease.

Regardless of the balance of causes, from the late nineteenth century through to the First World War, India faced multiple epidemics of infectious disease, including of malaria, cholera, influenza, and plague.

Interior of a temporary hospital for plague victims in Bombay, 1896-1897.

For instance, the bubonic plague, which arrived in India in 1896 on the heels of a massive famine, claimed at least ten million lives over the next two decades. Up to 95% of global mortality in this, the third great wave of plague in recorded history, occurred in India, even while the European population in the colony was largely insulated from the disease.

After World War I, developments both in India and internationally sparked calls for changes to India’s public health policy and spending. In 1919, changes to the structure of British administration gave Indians greater authority, though not necessarily more funding, to address health concerns.

Meanwhile, the new League of Nations prompted the collection of data that made it easier to compare mortality, morbidity, nutrition, and life expectancy around the globe, and India was found wanting in every regard. Within India, a growing nationalist movement condemned the British administration’s disregard for the population’s health. Outside the country, other governments began to view India (and Indians) as a source of contagion and called for restrictions on trade and migration.

The Seth Vishnudas Plague Hospital in Karachi, 1890

Two reports from this period capture both the tremendous hope, and the tremendous uphill battle, that lay ahead for proponents of public health in India. The first came from the National Planning Committee (NPC), a body constituted in 1937 by the Congress Party to chart its vision for independence. The second was from the Health Survey and Development Committee (or Bhore Committee), which was created by the British government in the waning days of its administration in 1943.

Both reports were critical of the imperial administration’s historic neglect of health and called for health services to be made available to all Indians. Looking to continental Europe and the Soviet Union as models, they envisioned an India where healthcare would be provided by the government as a right to all people regardless of their ability to pay, and where the health profile of the country would be comparable to the West.

To make this possible, the Bhore report called for an increase in state expenditures on health to at least 15% of government revenues, thus challenging the British administration’s longtime underfunding.

Medical inspection of women during plague outbreak in Sion Causeway, Bombay.

The grand vision reflected in the NPC and Bhore reports did not come to pass after Indian independence in 1947. The need was immense, as Indians faced some of the worst health outcomes in the world. To take just one measure, in 1950 life expectancy at birth in India was about 35 years, which was lower than the global average (45 years) and substantially worse than in the United Kingdom (68 years).

Although policymakers vowed to improve these grim statistics in an independent India free from British rule, the Indian government continued the colonial legacy of underfunding healthcare. During the first few decades after independence, the state prioritized other areas of development—especially industrialization—over health and welfare spending. Moreover, new health programs tended to be instrumentalist in their approach. Rather than viewing healthcare as a right in itself, the government linked health programs to achieving other goals.

This instrumentalist approach to health is clearest in India’s massive population control programs during the 1960s and 1970s. Viewing population control as a shortcut to economic development, the Indian government devoted a substantial proportion of its health budget to family planning programs that aimed to reduce India’s fertility rate. With the support of international agencies like the UN, the government of India separated family planning from maternal and child health and funded the former at the expense of the latter.

A postage stamp promoting family planning in India, 1966.

Despite significant state spending on family planning, therefore, the resources devoted to the health of mothers and children remained scarce. More broadly, although India had substantial resources, spending on healthcare infrastructure, especially in rural areas, remained woefully inadequate as the health of the population was sacrificed to other government priorities.

During the 1990s, the Indian government began a period of economic liberalization that signaled a further retreat from the earlier ambition to provide all Indians with healthcare as a right. As health services became more privatized, Indians who could afford it gained access to high-quality hospitals that offered cutting edge technologies. With its supply of highly-trained doctors—one recommendation of the Bhore report that was fulfilled—India became a hub of a growing medical tourism industry that welcomed wealthy patients from around the world.

Meanwhile, public healthcare services, which were the only services accessible to the majority of the population, were gutted even further. Patients in public hospitals were sometimes forced to scramble for medication and other needs even before the current COVID-19 crisis.

The Indian government today spends only 1% of its GDP on healthcare, one of the lowest rates in the world. In an echo of the colonial era, when government funds for health disproportionately benefited European enclaves, today’s India is characterized by vast health inequities with high quality care available for some, and a lack of resources for most others.

With this long history of inadequate funding and disregard for the health of ordinary people, India confronted COVID-19 with many disadvantages. However, history does not have to be destiny.

A COVID-19 antigen testing center in Warora, Maharashtra, India.

The failures of governance that led to the current crisis can and must be addressed. The immediate medical needs of patients, from the supply of medical oxygen to the provision of hospital beds, must be met. In the near term, a commitment to vaccine equity that does not privilege the former colonial powers at the expense of their former colonies in Asia, Latin America, and Africa must be the basis for any global health policy.

In the longer term, a social justice vision for health, with a commitment to adequate and equitable funding for health services for all people, is the only way to combat future pandemics and prevent the scale of tragedy we are seeing today.