Though his name is barely known in the West, the Emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707) stands out as one of South Asia’s most controversial historical figures. Today—365 years after ascending the throne as the sixth Mughal Emperor—his name elicits a range of emotional responses across the subcontinent, inspired more by modern politics than historical reality.

In popular media and some academic literature, he has been accused of a variety of misdeeds, such as banning music, destroying thousands of non-Islamic monuments and temples, and committing genocide.

To some South Asian Muslims, he was an exemplary orthodox ruler, whose conquests brought Indo-Islamic power to its territorial height. To others, he was a religious fanatic whose intolerance instigated the communal violence that plagues South Asia today.

To Hindu nationalists, he is the ultimate villain: an oppressive fundamentalist who led a genocidal campaign against Hindus and should therefore be wiped from the history books (as was the recent fate of the entire Mughal Empire in the Indian educational curriculum).

In a similar vein, Western Orientalist scholars painted Aurangzeb as a despot and blamed him for weakening the Mughal state and thus opening the door to British colonization. Scholars have only recently started challenging this narrative of Mughal decline to acknowledge various other economic, social, political, military, and environmental factors.

As part of this reconsideration, they have sought to uncover a more nuanced picture of Aurangzeb himself, separate from the inherited biases of earlier generations and current political movements.

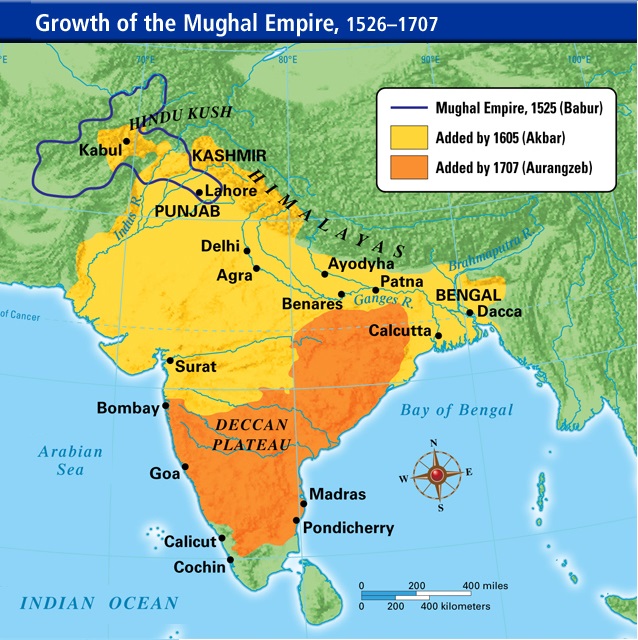

When Aurangzeb took power, the Mughal Empire had ruled large parts of India since its founding in 1526 by Babur, a prince from Central Asia. Under Babur’s descendants, the empire steadily expanded and emerged as one of the wealthiest and most powerful states in the early modern world.

The Mughal emperors centralized power around themselves, implemented an efficient tax system, introduced legal protections for peasants, and incorporated members of India’s diverse religious and ethnic landscape into their administration. All this, combined with an influx of new, highly productive crops from the Americas—such as corn, potatoes, tomatoes, and peppers—created an era of abundance, prosperity, and relative stability.

This prosperity was projected to the world through various cultural projects, from exquisite miniature paintings to architectural masterpieces, such as Humayun’s Tomb, the Red Fort in Delhi, and, most famously, the Taj Mahal. The latter was built by Aurangzeb’s father, Shah Jahan, as a tomb for his beloved wife (and Aurangzeb’s mother), Mumtaz Mahal.

Issues of succession, however, created fractures within the Mughal Empire. While in most European monarchies, the eldest son inherited the throne upon his father’s death, this was not the case for the Mughals.

Instead, following Central Asian tradition, every prince had an equal claim to the throne. This proved to be a double-edged sword. While succession struggles provided long-term stability by ensuring that the most capable prince would lead the empire, they were chaotic and bloody in the short term.

The most dramatic of these struggles was the one that brought Aurangzeb to the throne in 1658. The tensions between Aurangzeb and his three brothers were so great that the war of succession broke out not after their father died, but when he simply fell ill and continued despite his recovery.

While all four of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal’s sons jockeyed for power, the contest came down to the eldest and favorite, Dara Shikoh, versus the third son, Aurangzeb. In the end, Aurangzeb triumphed, executing Dara and imprisoning Shah Jahan.

As a ruler, Aurangzeb was pious but not—as he is often accused of being—puritanical. He was personally devout but continued to offer legal protections to and employ large numbers of Hindus and members of other religious groups. In fact, the Mughal nobility during Aurangzeb’s reign had a higher percentage of Hindus (just over 30%) than under any of his predecessors.

When forced to choose between political expediency and religious orthodoxy, politics generally won out. He would ally with Hindu rulers against Muslims when it suited his military goals. When he did target Hindu or Sikh religious leaders, it was in response to political threats rather than religious intolerance.

Much attention has been paid to his misguided reinstatement of the jizya tax on non-Muslims, which was used as a rallying cry against Mughal rule, though its actual collection was always half-hearted and inconsistent.

While much focus has been placed on the supposed cultural contraction during his reign, Aurangzeb’s main emphasis was always on military expansion. He relentlessly pursued the conquest of central and southern India yet achieved only lukewarm and incredibly costly success. While he did expand the empire to its greatest territorial height, his conquests were unsustainable.

His successors proved unable to maintain the vast territory that Aurangzeb managed to conquer, especially in the face of various political and environmental challenges that arose throughout the eighteenth century. These challenges saw Mughal power incrementally diminished until its end in 1857 when it was formally replaced by British crown rule.

Aurangzeb and the Mughals have become fodder for competing modern ideologies. While a recent article published by Indian scholars provided a map of Hindu temples destroyed by Aurangzeb, there was no complimentary map—or even mention—of the ones he allowed to be built or restored, let alone the thousands he left untouched.

The perspective provided in these types of articles isn’t completely inaccurate, but it does depict a purposefully narrow view of Aurangzeb and his policies, focusing on destruction and using cherry-picked evidence to pursue a larger anti-Muslim political agenda.

The truth is that Aurangzeb does not fit into modern boxes that fix a person’s identity on a single axis. He was not a proto-Taliban or ISIS-style fundamentalist, nor did he conceive of or treat Hindus as a single sectarian whole. He did not ban music, nor did he commit genocide. While he would not meet modern definitions of a good leader, he wasn’t attempting to, nor should he or any historical figure be held to modern standards.

It is only by studying Aurangzeb and the Mughals on their own terms, as products of and actors in their specific historical context, that we can move away from polarizing caricatures and measure their true impact on the world.