The Chinese government's campaign against the Uyghur people of Xinjiang Province has turned the region into perhaps the largest incarceration and surveillance state on the planet. This campaign is not the result of any particular recent event but rather, as historian Adeeb Khalid explains, it is rooted in competing notions of nation, empire, and culture that go back several centuries.

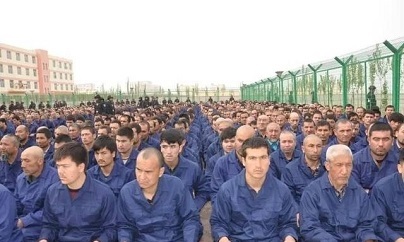

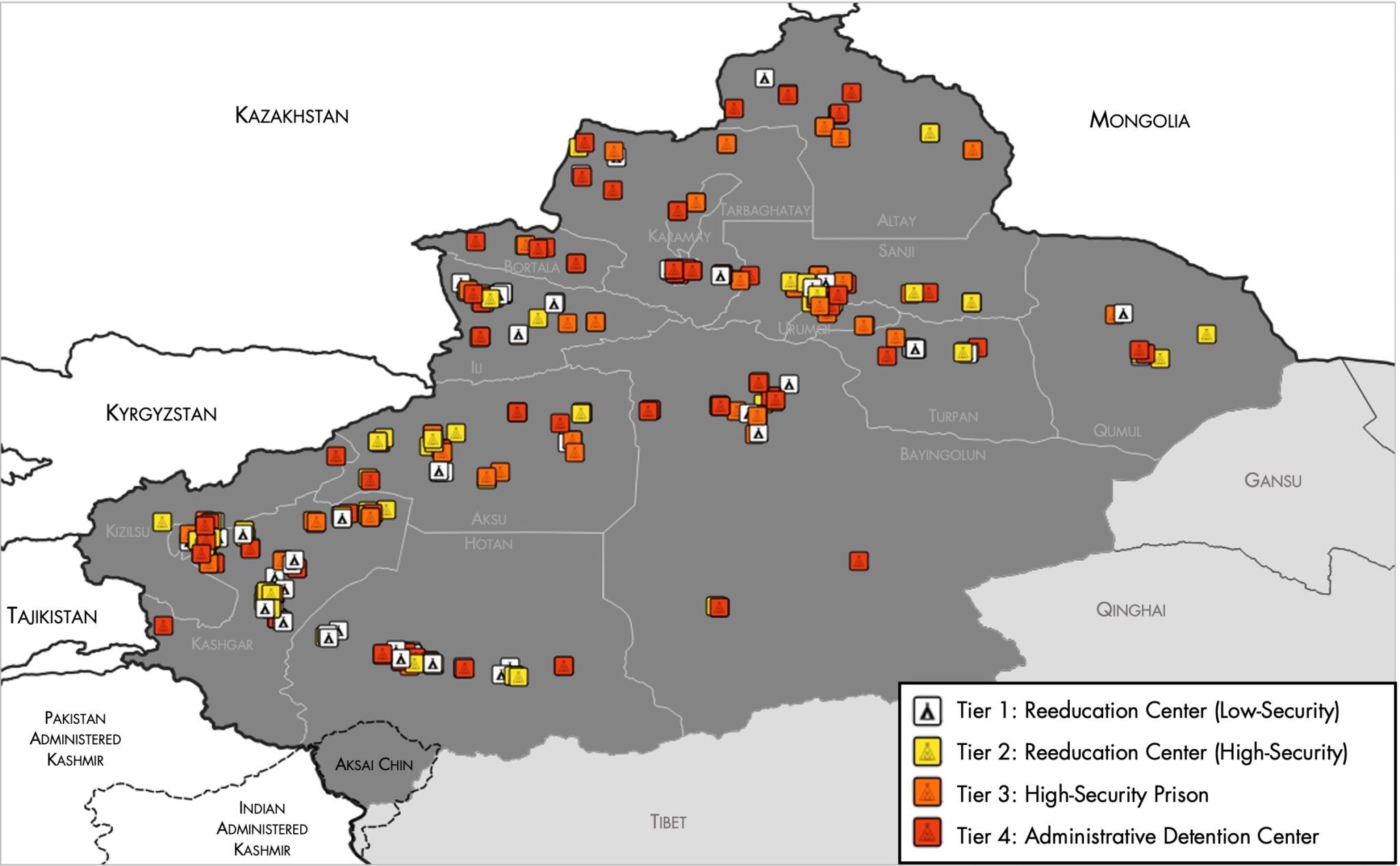

In the fall of 2016, the Chinese government embarked on an unprecedented campaign of mass incarceration of the Uyghur population in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. A vast archipelago of camps — massive structures surrounded by watch towers and barbed wire — sprang up to swallow a significant percentage of the Uyghur population.

By 2019, when the campaign had extended to other Muslim populations of the province, the camps held an estimated 1.5 million people. The camps were supposed to “re-educate” the inmates, “cleanse their brains of harmful thoughts,” and “give them a healthy heart attitude.” The internees included men and women, and they came from all walks of life—ordinary people but also intellectuals, artists, and celebrities. Many noted figures disappeared and have not been heard from since.

Life outside the camps has not been much better. Police stations—“convenience security points”— sit on every other street corner and in all important locations in urban areas. Security cameras equipped with face-recognition technology and mounted on street corners, walls, lamp posts, as well inside businesses, track ordinary citizens.

High speed cameras strung along streets and highways capture license plates of vehicles as they pass. Checkpoints along highways, at gas stations, and in many other locations scan identity cards and faces and check them against biometric data stored in state-run databases.

Police patrols are equipped with devices that can scan irises as well as faces and they have the right to check citizens’ smartphones to see if they carry unauthorized content or “harmful information.” Xinjiang became a dystopian surveillance society the likes of which the world had never seen.

Why did China launch this campaign of incarceration and close supervision? The answer lies in a long struggle between the Chinese state and the Uyghurs that is rooted in a history of empire and, more recently, of settler colonialism. It is also based on competing visions of history and of who belongs to the land.

Two Views of the Same People

The conflict begins with basic nomenclature. Xinjiang is a Chinese term that means “New Dominion.” It was coined in 1884 when Xinjiang was raised to the status of a province, meaning that it acquired the same administrative structures as provinces in China proper. It is the only term the state permits. It may not lawfully be translated.

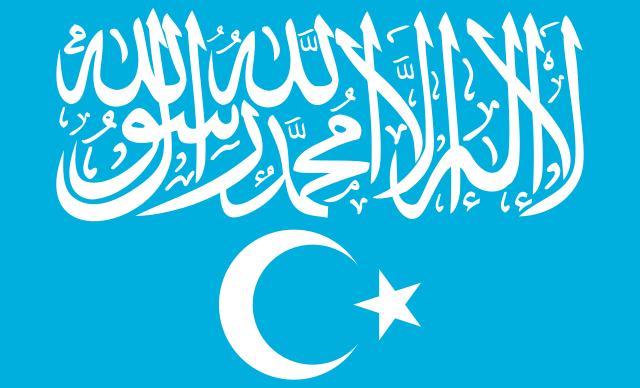

The Uyghur term for the province is a direct transliteration: Shinjang. Many Uyghurs would rather use the term “Eastern Turkestan” (Shärqiy Turkistan) or simply “the Uyghur homeland” (Uyghur diyari) if they were allowed to do so.

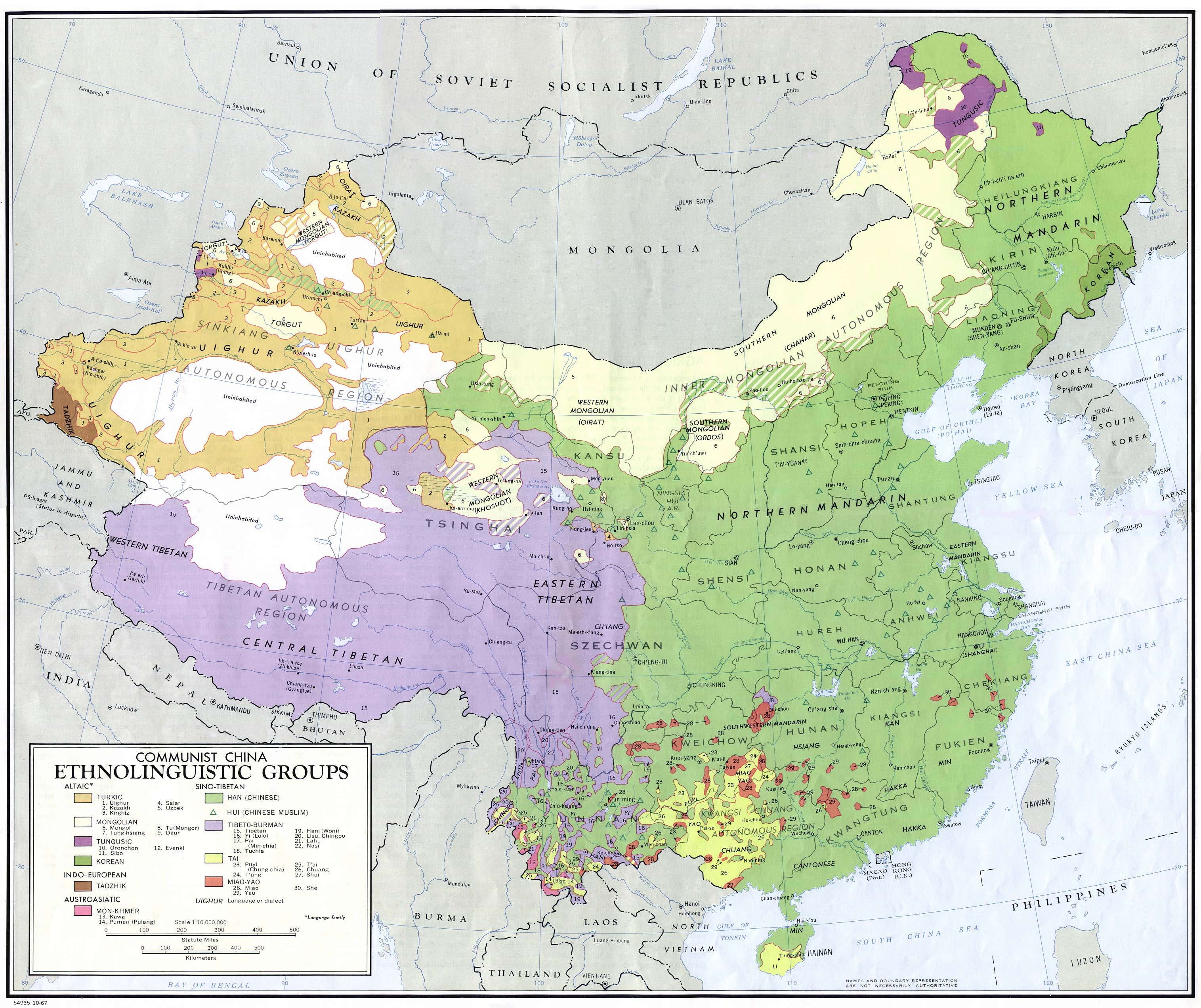

Western commentators often suggest that Uyghurs are closer to Central Asians than to the Chinese. That view is a bit off the mark. The Uyghurs are Central Asians who ended up in China as a result of imperial conquest. The Uyghur language is quite close to Uzbek and has nothing in common with Mandarin.

The Chinese state claims that “Xinjiang has, since the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC–24 AD) … been an inseparable part of the unitary multi-ethnic Chinese nation.” In other words, the Chinese nation has existed across time and Xinjiang has always been a part of it, although internal weakness and foreign intervention have interrupted that unity. The People’s Republic sees itself as the embodiment of an eternal China that has existed for millennia.

The Uyghurs hold a rather different view. They see the province as their ancestral homeland, a land conquered by foreign forces in historical time. For most Uyghurs, the story is of colonial conquest and continued occupation by an alien power.

The memory of two failed attempts at national statehood in the 20th century (two different Eastern Turkestan Republics were proclaimed in 1933 and 1944) competes with the reality of demographic transformation wrought by the Chinese state since the establishment of Communist rule in 1949.

A Different Chronology of Uyghur History

The official Chinese claim is teleological and deeply problematic. The Western Han dynasty might have laid claim to the region that is now Xinjiang, but it is not clear how effective the control was or how deep an affinity the inhabitants of the region felt toward the Chinese state. The Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) was the last time a China-based empire claimed any control over Xinjiang before the 1750s. In 751, defeat by Arab forces in the Battle of Talas in what is now Kyrgyzstan led to a Tang retreat.

Over the next few centuries, the largely Turkic speaking population of Xinjiang converted to Islam, and “China” became a distant and mysterious realm for Central Asians.

It was a conflict between two non-Muslim and non-Chinese empires in the eighteenth century that made today’s Xinjiang a part of “China.”

In the first half of the seventeenth century, Manchu warriors conquered China proper and established the Qing empire (1636-1912). The Manchus shared many aspects of the political tradition of Inner Asia. They were always careful to distinguish themselves from the Han Chinese, even if the latter group had a demographic majority.

At about the same time as the Qing emerged, the Zunghars, a western Mongol people, established an empire in Inner Asia. It was a nomadic empire in the tradition of the Mongol empire of Chinggis Khan. Based in the northern parts of present-day Xinjiang, it also brought under its control the predominantly Muslim southern region.

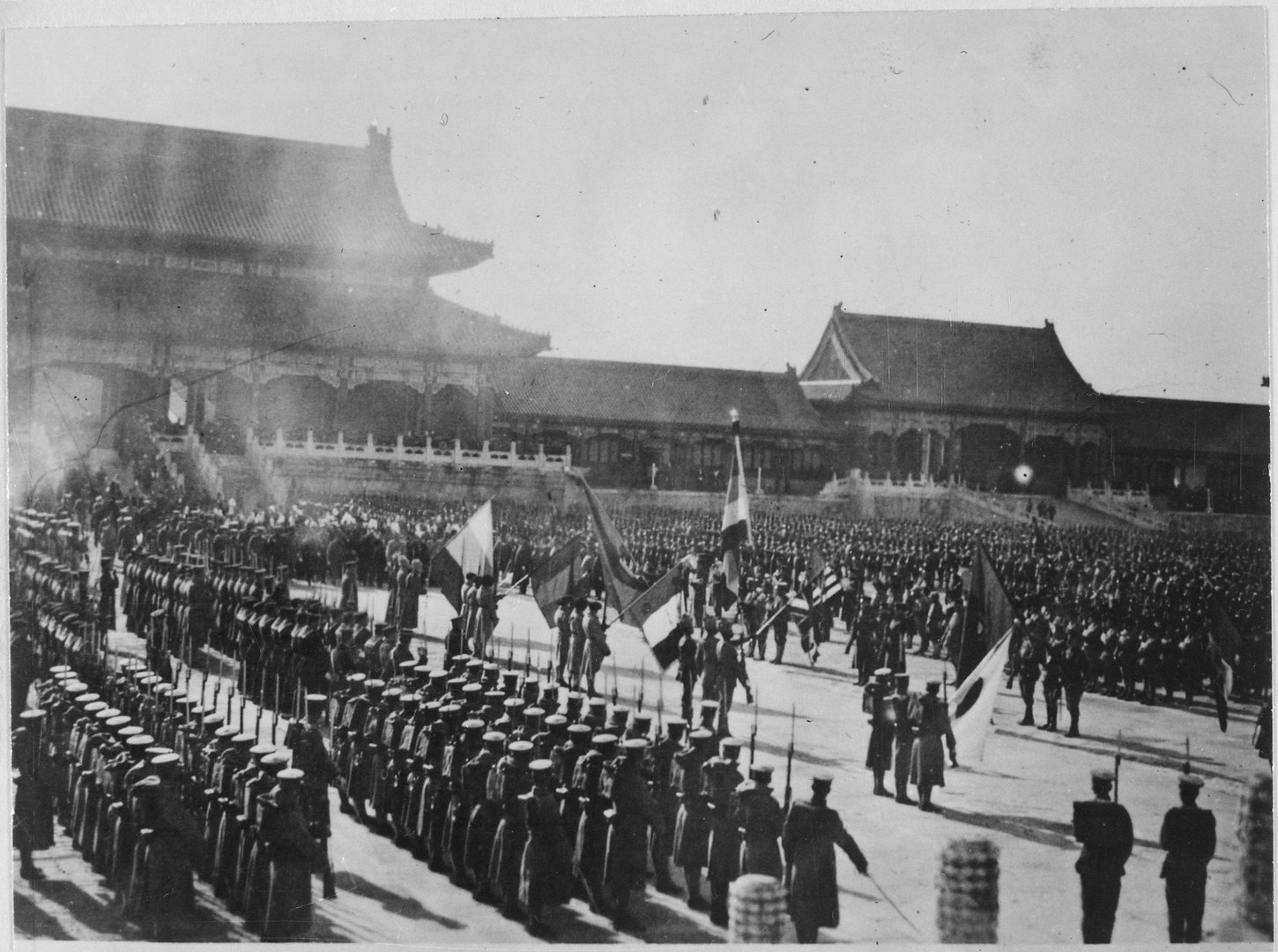

The Zunghars were competitors of the Qing and soon got into a long-term conflict with them. In the 1750s, the Qing launched an all-out assault on the Zunghars and vanquished their empire. One of the fruits of this victory was the Qing conquest of Eastern Turkestan. Thus the “Uyghurs” came to be part of “China.”

The Qing ruled their newly acquired territory with a light touch. Still, they faced numerous rebellions, one of which brought their rule crashing down in 1864. By then, the Qing were a beleaguered empire, pressed by European powers externally and beset with revolts at home. Few observers expected the Qing to recover, and many among the Qing elites did not think Xinjiang was a prize worth keeping. Nonetheless, the empire mounted an offensive that managed to reconquer the territory in 1881.

The empire’s ambitious plans to integrate the territory into China were easier proclaimed than implemented. Western powers forced the Qing to sign unequal treaties that allowed their subjects to trade freely and to be exempt from Qing law. The Russian empire thereby acquired enormous economic influence in Xinjiang. At the turn of the twentieth century, Xinjiang was more a colony of Russia than of the Qing.

Faced with demands for political, economic, and territorial concessions, the Qing began to argue that their realm was a single state whose territory was indivisible and inviolate. This claim—that the Qing empire was a nation-state—has been the one constant of Chinese history since the early 20th century. It has been repeated with great insistence by all regimes that have ruled the country, Qing, Nationalist, and Communist alike.

China was being humiliated and its rulers could not seem to do anything about it. One response was the rise of an insistent Han Chinese nationalism that saw the Manchu regime not only as venal and corrupt, but also as foreign. A nationalist, anti-Manchu revolution toppled the dynasty in 1911–12 and proclaimed a republic.

New Government, Same Ambitions

The leaders of the new republic wanted to be rid of the Qing, but they had no desire to part with the empire the dynasty had built. As Mao Zedong put it many decades later, “China is a country vast in territory, rich in resources and large in population; as a matter of fact, it is the Han nationality whose population is large and the minority nationalities whose territory is vast and whose resources are rich, or at least in all probability their resources under the soil are rich.” Those vast territories could not be let go.

Still, the republic recognized the heterogeneity of the country’s population and saw itself as “a union of five races” — Han, Manchu, Mongols, Tibetans, and Muslims. Yet this unity was very much a Han Chinese idea about which the other four “races” were not consulted. The Mongols opted out of the republic, declaring their independence. The Tibetans tried to follow suit and sought support from British India.

The Uyghurs, for their part, were developing a completely different vision of nationhood. Activists were beginning to imagine the Muslim inhabitants of Eastern Turkestan as a national community of their own, one connected by ties of language and culture to the rest of Central Asia and the Ottoman Empire.

Local intellectuals rediscovered the term “Uyghur,” the name of a Turkic empire in the region that flourished in the 8th and 9th centuries, which they adopted as the name for their national community. As they imagined their place in the world, they looked westward, rather than to the rest of China.

The new Chinese republic quickly disintegrated and descended into a slow-motion civil war that lasted until 1949. Xinjiang was largely cut off from the center, and for 28 years between 1916 and 1944 it was ruled by Han Chinese governors who exercised power on their own, often in open defiance of the central government but with a clear intent of keeping power in Han Chinese hands — and keeping the local population in its place.

The Uyghurs in a Period of Turmoil

Meanwhile, the Russian Revolution of 1917 brought significant changes to Xinjiang. The tsarist empire collapsed in February 1917 in the face of mass protests brought on by the disasters of World War I. By the end of the year, the Bolsheviks, a party of radical Marxist revolutionaries, had come to power and established the world’s first socialist state.

Most non-Russians in the empire saw the revolution as a moment of national, not class, liberation and sought to maximize national rights in the new order. The Bolsheviks offered “self-determination” to the various nationalities of the empire by means of territorial autonomy. In 1922, the former Russian empire was reconfigured as a federal union of allegedly sovereign republics based on the national self-determination of different nations, all within a Soviet context.

This model of managing ethnic and national difference would spread around the world in the 20th century with a massive impact on the place of Uyghurs in the Chinese state.

The Soviets were also keen to spread revolution around the world. China for them was an important front in the global struggle against imperialism (and therefore capitalism), and they supported both the Guomindang (the Nationalist Party) as well as a nascent Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The main channel of Soviet influence in China was the Communist International (or Comintern). Its representatives introduced into Chinese politics Soviet notions of recognizing nationality and granting territorial autonomy.

The search for the place for Uyghurs in the Chinese state continued. The central government did not control Xinjiang, yet it remained suspicious of Uyghur claims of autonomy.

Events took their own course on the ground. Uyghur activists declared two different independent republics in 1933 and 1944. They had different political orientations and neither succeeded, but they are both remembered today by many Uyghurs as failed attempts at national statehood.

Events in China proper defined Xinjiang’s fate. In 1949, the CCP won the civil war against the Guomindang and took power. Xinjiang was far away from the front lines of the civil war and saw little action. Rather, the Guomindang ceded the province to the Communists. With substantial help from the Soviets, the CCP occupied the region in what came to be known as “the peaceful liberation of Xinjiang.”

The Communist takeover transformed the relationship between Xinjiang and China. For the first time since the Qing conquest of the 1750s, the province began to be fully integrated into to the Chinese state.

Revising the Soviet Model

The CCP adopted several aspects of Soviet nationalities policy but in diluted forms. It recognized national diversity and formally categorized the non-Han population of the country into 55 minzus (ethnic groups), each of which was to be characterized by a distinct language, culture, folklore, and costume. Official rhetoric insisted that each minzu was “the master in their own house.”

However, the CCP had always seen its mission as a national one. Communism was its way of ending China’s “humiliation” at the hands of foreign powers. It was just as committed to ensuring the territorial integrity of China as the Guomindang. Being “master their own house,” therefore, could not mean that minzus had the right to self-determination. Autonomy did not lead to federalism.

Rather, the People’s Republic emerged as a “unitary multi-ethnic Chinese nation.” The officially recognised minzus, along with the demographically predominant Han, are part of a single whole (often cast as the formula of 55+1=1). By this logic, all Chinese citizens are indigenous to the whole country—and thus the Han belong in Xinjiang or Tibet as much as those regions’ indigenous populations do.

Indeed, the People’s Republic has long sought to transform the demographic character of Xinjiang through a deliberate policy of implanting Han Chinese in the province.

In 1949, scarcely 5% of the population of the province was Han Chinese. Today the number is closer to 45%. In the 1950s, demobilized soldiers were settled on the land, and during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), many urban youth were “sent down” in rustication campaigns. Since the 1980s, economic incentives and job preferences have drawn Han Chinese to Xinjiang.

Unlike in the Soviet Union, the party and the state make no pretense of assuring representation of minzus in positions of leadership. Han cadres from China proper always have headed the Xinjiang bureau of the CCP, the most powerful institution in the province. This is a form of settler colonialism implemented by a Communist regime.

Nevertheless, there was some space for Uyghurs to create a national culture. In the 1950s, the state set up institutions for linguistic, ethnographic, and historical research on the Soviet model. The madness of the Cultural Revolution interrupted these endeavors, but activity resumed during the Reform Period inaugurated in 1978.

Because academic research was politically constrained, the historical novel became the most important form for the elaboration of a Uyghur national narrative. Even then, Uyghurs ran up against sharply drawn limits of expression.

The Post-Soviet Crackdown

The dissolution of the Soviet Union made the CCP rethink its minzu policy. The lesson that the CCP learned from the Soviet collapse was that the Soviets had given too much freedom to the “minorities,” who then used it to destroy the country. Since 1991, the rights accorded to the minzus, never extensive to begin with, have been gradually curtailed.

The Chinese state has increasingly insisted that all Chinese citizens belong to a single nation with a single, all-encompassing culture. The formula of a “unified multiethnic state” reduces national minorities to mere ethnicities and assimilation into the common “national” culture becomes the goal.

Flooded by Han Chinese settlers and faced with the further retrenchment of minzu rights, many Uyghurs felt like strangers in their own home. As the 21st century dawned, Xinjiang’s cities were socially segregated, with little interaction between Uyghurs and Han Chinese. Ethnographers documented everyday forms of resistance, from satire and private mockery to a refusal to accept official categories and proclamations.

The 1990s and 2000s also saw an upsurge in Muslim piety among the Uyghurs. This was part of a phenomenon common to all Muslim societies, facilitated by the opening up of Xinjiang to the outside world. But it was also a form of resistance to Chinese rule. The new piety, with the adoption of modest dress by women, increasing abstention from alcohol, and the construction of new mosques, further reinforced the boundaries between Uyghurs and the Han.

It was clear that the views of most Uyghurs and of the government are fundamentally opposed and to a large degree mutually exclusive.

Resistance sometimes turned into violence. During the 1990s and 2000s, a number of mass protests turned into riots or attacks on police stations or other symbols of the state. Then came the Urumchi riots of July 2009.

Activists organized a mass demonstration in Urumchi (the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region) to protest the killings of Uyghur migrant workers in a town in south China by a Han mob and to seek justice for the victims. Police assaulted the demonstrators who then turned violent, attacking not just the police but also Han-owned businesses.

Two days later, Han vigilantes launched a counterattack on Uyghur neighborhoods, repaying the Uyghur attacks with interest. It took several days for order to return. Official figures put the death toll at 197; there was massive property damage as well.

From “Separatism” to “Terrorism”

Until 2002, China had blamed Uyghur discontent on “separatism” and “pan-Turkism,” the latter a bogeyman once used by the Soviets. In 2001, the state started using the language of antiterrorism that was authorized by the US-led Global War on Terror (GWOT). Now, Uyghur discontent was put down to the “three evils” of separatism, religious extremism, and terrorism.

In October 2001, China asserted that Uyghur activists in exile (“Eastern Turkestan elements”) had deep links to Al Qaeda. The following year it convinced the U.S. government to put a Uyghur exile group, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), on its list of international terrorist organizations even though the group was a tiny militia in Afghanistan. Since then, the Chinese state has blamed most unrest in Xinjiang on ETIM and other “Eastern Turkestan elements” and demonized all Uyghur discontent as inspired by terrorism and religious extremism.

There is no evidence that events in Xinjiang are tied to outside forces, whether Uyghur exiles or international Islamist networks. But the language of GWOT is now a universal language that places those accused of terrorism beyond the realm of humanity and turns them into a universal enemy.

After 2009, the Chinese government seems to have decided that Uyghurs as an entire community were afflicted with extremism and hence disloyalty, the sources of which are in Uyghur culture and Islam. In 2014, the Chinese government launched a “People’s War on Terror,” which combined the language of GWOT with a Maoist-style campaign.

Uyghurs were called upon to “make terrorists become like rats scurrying across a street, with everybody shouting ‘beat them.’” This was to be accompanied by re-education that would cleanse the brains and “thoroughly reform them towards a healthy heart attitude.”

In August 2016, Chen Quanguo was appointed Communist Party Secretary of Xinjiang. He ratcheted up the People’s War on Terror to include “de-extremification” through “re-education.” That is when the campaign of incarceration and surveillance took on its current form.

“De-extremification” is accompanied by sustained attempts at Sinicizing Uyghur culture and Islam itself. Uyghurs should “remain committed to removing extremism from eating” (that is, they should not avoid pork), conduct all public interaction in the “national language,” and remove all Islamic symbols not just from public spaces, but from their homes.

Chen’s term ended in late 2021 and he was replaced by Ma Xingrui, a technocrat. Some rules seem to have been relaxed, but the camps have not emptied, and most internees are still missing. The security state that Chen built seems to have become the new normal.

The current focus of China’s Xinjiang policy is defined as “resolutely thwarting attempts to ‘control China with Xinjiang’ and ‘contain China with terror.’” Western powers try to control China by criticizing its policies in Xinjiang while Islamists allegedly attempt to contain China by using terror. If this is how the Chinese government sees the world, then the new normal is here to stay.

James Millward, Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, revised and updated, edition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

David Brophy, Uyghur Nation: Reform and Revolution on the Russia–China Frontier (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2016).

Gardner Bovingdon, The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

Sean R. Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Campaign against Xinjiang’s Muslims (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).

Adrian Zenz, “‘Thoroughly Reforming them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude’: China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang,” Central Asian Survey, 38 (2019).

Living Otherwise blog — edited by Darren Byler, an excellent source for thoughtful and well informed commentary on current developments in Xinjiang.

Xinjiang Victims Database — a database that seeks to document individuals swallowed up by the carceral regime