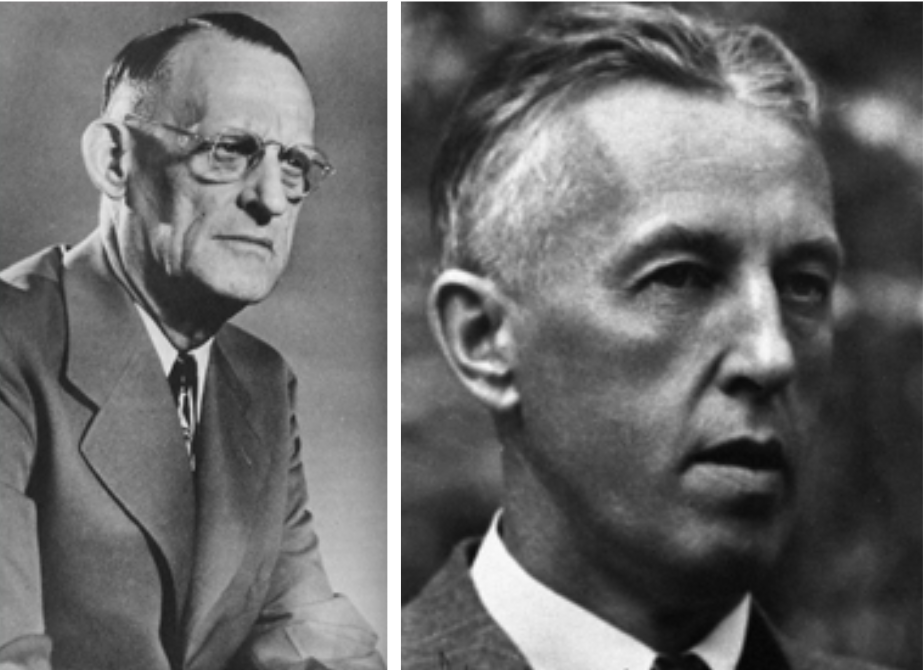

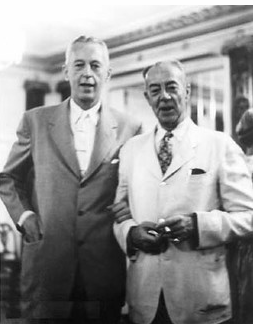

Two individuals struggling with long-term alcoholism, Bill Wilson, a New York stock speculator, and Dr. Bob Smith, an Akron, Ohio surgeon, co-founded Alcoholics Anonymous in Akron when they met for the first time on June 10, 1935.

This chance meeting of two people desperate to stay sober gave rise to an organization that today estimates an active membership of nearly two million participants in over 120,000 groups across 160 countries. AA operates at no cost to participants and provides a non-professional self-help framework for recovery that has been widely adapted to benefit individuals with a variety of addictions.

AA has its roots in the Oxford Group, a conservative evangelical Christian organization.

In the early 1930s, Rhode Island businessman Roland Hazard sought help for his alcoholism from Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung. Jung suggested that alcoholism might only be overcome through a profound spiritual experience. Following Jung’s advice, Hazard joined the Oxford Group, which emphasized confession of sins, spiritual rebirth, and surrender to God.

Although not specifically focused upon alcoholism, some Oxford Group members recovered from alcoholism by embracing the group’s principles. After finding sobriety, Hazard contacted others struggling with alcohol including Edwin “Ebby” Thatcher, a former drinking companion of Bill Wilson. Thatcher achieved sobriety and recruited Wilson who joined the Oxford Group.

Wilson had his last drink of alcohol on December 11, 1934, when he admitted himself, for a fourth time, to Towns Hospital in New York City under the care of Dr. William Silkworth. Considered an expert in the treatment of alcoholism, Silkworth was among the first to propose a disease rather than a moral model of alcoholism. During this hospitalization Wilson had a “spiritual experience” that he described as breaking the bond of his addiction.

In the Spring of 1935, the newly sober Wilson was on the verge of returning to drinking while on a difficult Akron business trip. Rather than drinking, he sought another alcoholic to talk with. Working through local church directories, Wilson found Henrietta Sieberling, an Oxford Group member.

Sieberling took Bill to a fellow member Bob Smith who had also long struggled with alcoholism. Wilson and Smith formed a connection that Smith attributed to their shared understanding of the experience of alcoholism. Wilson avoided relapsing and Smith soon achieved sobriety. The importance of Sieberling’s introduction cannot be overstated. But for that chance meeting there may have been no AA.

Continuing to work with other alcoholics, Wilson and Smith became discouraged by the Oxford Group’s focus on evangelizing, lack of group democracy, and repeated encouragement from Oxford Group leadership for them to reduce their work with alcoholics. As a result of these conflicts, they left the group in 1937.

In the early days of AA, the group operated as a “word of mouth program,” with members carrying the message to those seeking recovery. That early oral tradition promoted six steps to recovery. Though there were multiple versions of the six, all took this general form:

We … (1) admitted we were licked; (2) got honest with ourselves; (3) talked it over with another person; (4) made amends to those we had harmed; (5) tried to carry this message to others with no thought of reward; (6) prayed to whatever God we thought there was.

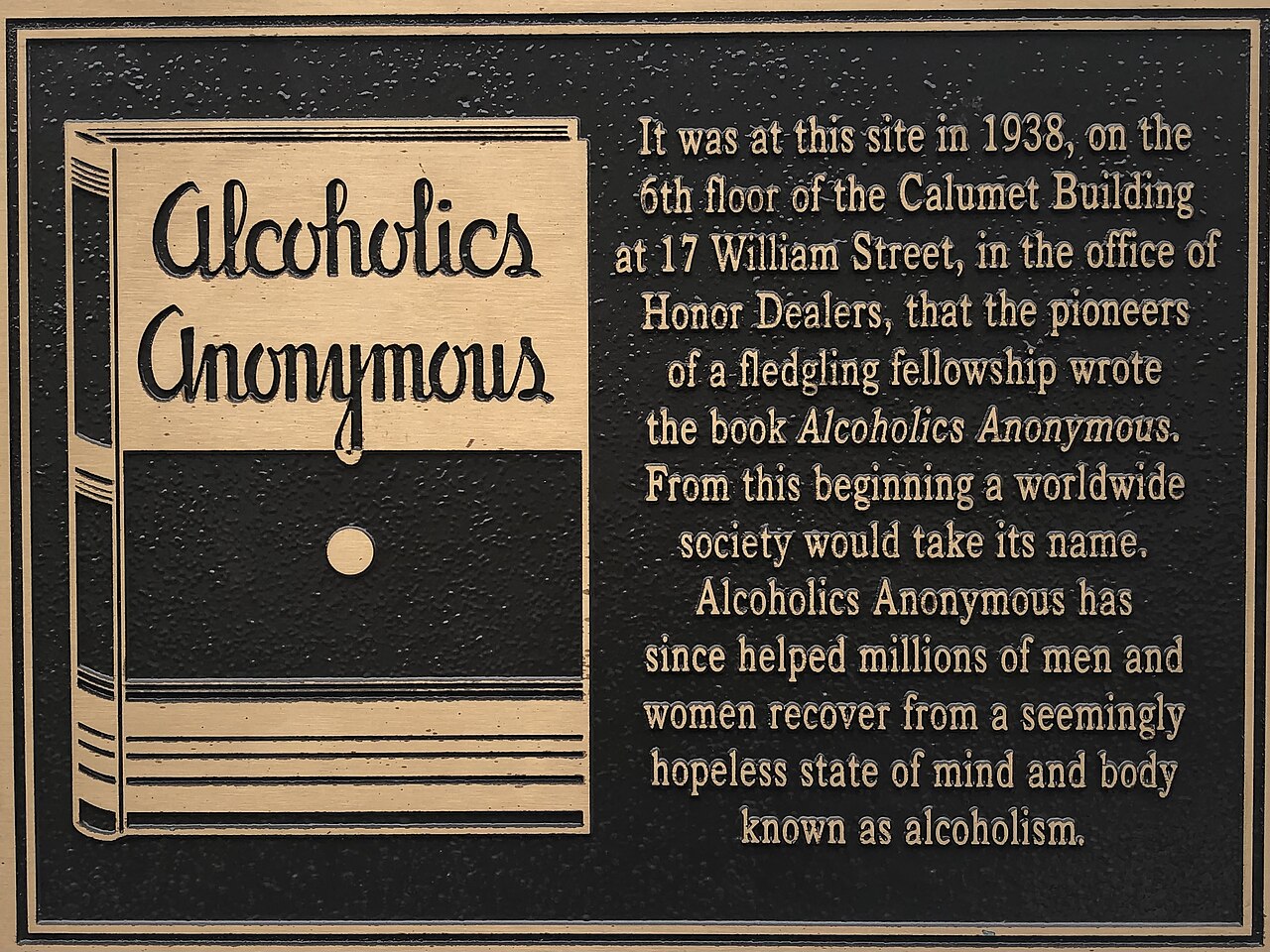

In 1939, Wilson authored the book Alcoholics Anonymous. There, he expanded the initial six principles to today’s well known 12 Steps, and included personal stories authored by early members. Now in a fourth edition and known to the original members as the Big Book (not for its impact but because of the thickness of the paper used to save costs in the first printing) the text has sold over 30 million copies.

The lack of democracy that led the founders to leave the Oxford Group informed Wilson’s writing of the Twelve Traditions of AA. His article “Twelve Suggested Points for A. A. Tradition” appeared in AA’s monthly journal, The Grapevine in 1946. The Twelve Traditions were formally adopted in 1950 and established a highly decentralized organization without a central leader: “A.A … ought never to be organized … our leaders are but trusted servants; they do not govern.”

AA was to be an organization with a clearly articulated purpose—“to carry the message to the alcoholic who still suffers”—and one that sought to avoid distractions and controversy that might detract from its primary purpose: “Alcoholics Anonymous has no opinion on outside issues …”. Though less well known than the Twelve Steps, the traditions contributed significantly to the growth and longevity of AA.

Based on these traditions, each AA group has no leaders, just volunteers who set up meeting spaces and conduct other functions. All group decisions are made by consensus.

Meetings generally begin with a series of readings, such as the Twelve Steps. After this, some meetings allow individuals to discuss their recovery and explore specific recovery topics. Others might have one speaker, who shares what life was like before AA, how they found AA, and how their life has improved since.

Critics have characterized AA as cult-like, suggesting that it is ineffective in promoting recovery from alcoholism.

However, several recent rigorous reviews have found that AA is superior to many other treatments in its ability to increase abstinence, and equally effective to those treatments in mitigating other alcohol-related outcomes, including reducing healthcare costs for people with alcohol use disorders.

AA is not for everyone.

Just as the founders disassociated from the Oxford Group because of the strong emphasis on evangelizing, some find AA’s emphasis on a Christian “God” as inconsistent with their own belief systems.

Similarly, although 38 percent of AA members identify as female, many women find AA concepts of powerlessness and humility to be anathema to the sense of disempowerment and misogyny that shapes the experiences of many women in society. AA encourages members to attend AA long enough to see if it works for them.

There are many effective paths to recovery from addiction. AA is one.

![]()

Learn More:

AA Agnostica. Retrieved from https://aaagnostica.org/

Anonymous. (2001). Alcoholics Anonymous: The story of how many thousands of men and women have recovered from alcoholism (4th ed.). New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services.

Bufe, C. (1998). Alcoholics Anonymous: Cult or Cure (2nd ed.). Tucson, AZ: See Sharp Press.

Gross, M. (2010). “Alcoholics Anonymous: Still sober after 75 years,” American Journal of Public Health, 100(12).

Kelly, J. F., Humphreys, K., & Ferri, M. (2020). “Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(3), Art. No.: CD012880.

S. Aruther. (2014). A Narrative Timeline of AA History: Public Version. https://archive.org/details/2014-narrative-timeline-of-aa-history

Speaking of Jung. (2015, November 13). The Bill W. Carl Jung letters. Retrieved from https://speakingofjung.com/blog/2015/11/13/the-bill-w-carl-jung-letters

The New York Times. (2019, December 27). “Alcoholics Anonymous and women.” Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/27/opinion/alcoholics-anonymous-women.html

Wilson, B. (1946). “Twelve suggested points for A.A. tradition.” The Grapevine, 2(11), 2–3.

Wilson, B. (1952). Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services.

Wilson, B. (1985). Alcoholics Anonymous Comes of Age. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services.