On December 12, 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a 5-4 decision in the Bush v. Gore case. It put an end to the disputed presidential election held that year.

The five-person majority found that the State of Florida was obliged to report its final presidential election results by December 12th, and thus that manual recounts of the returns in that state had to stop.

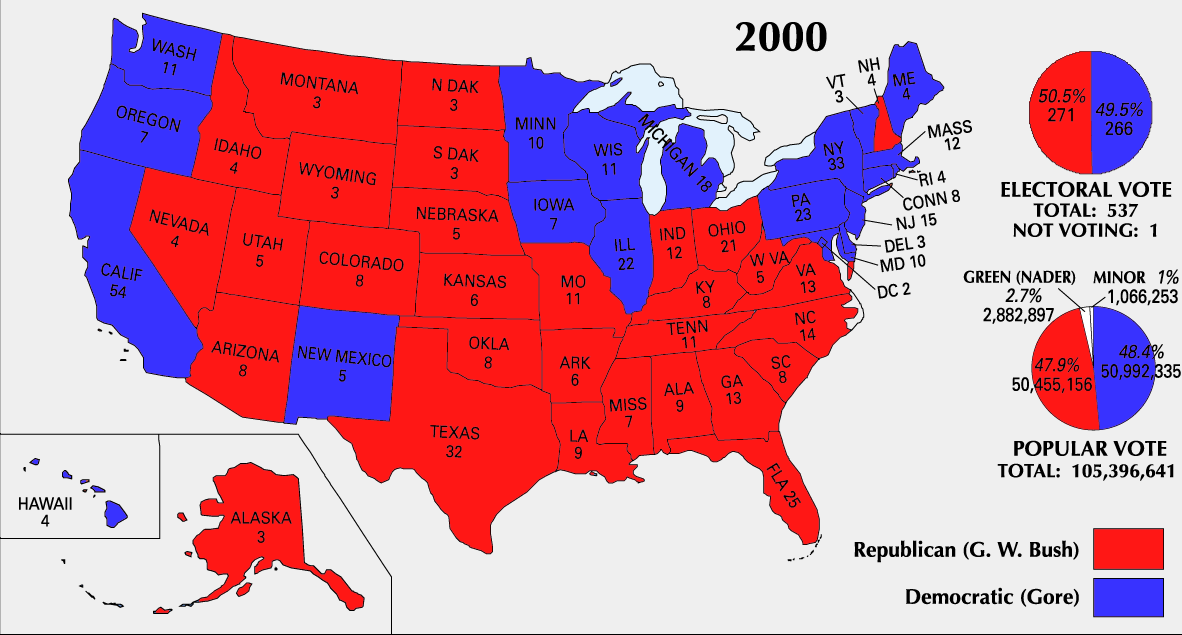

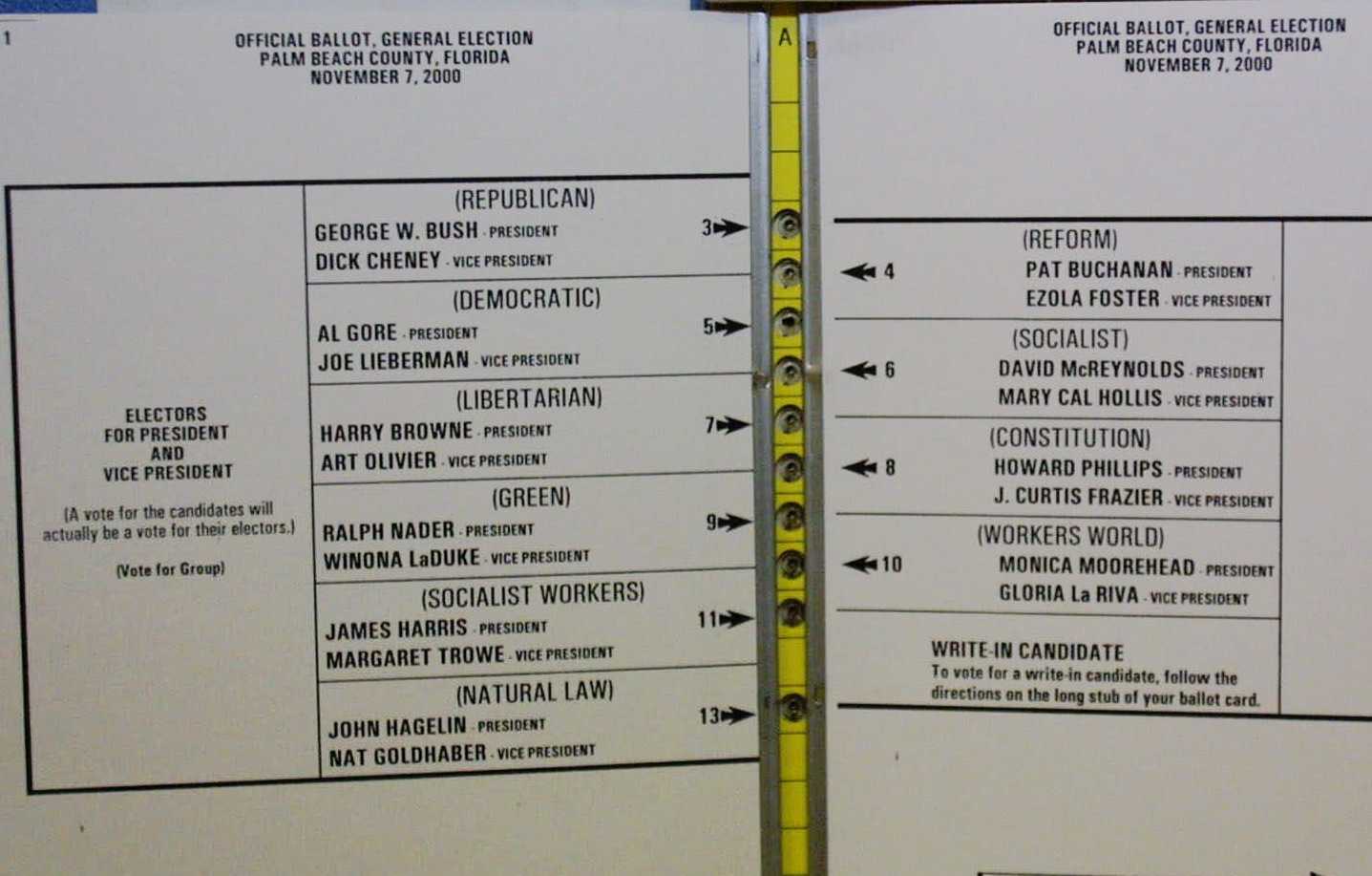

That finding preserved George W. Bush’s tiny lead of 537 votes out of almost six million cast, thereby giving him Florida’s 25 electoral votes and, as a direct result, a majority of 271 (one more than needed) in the Electoral College tally.

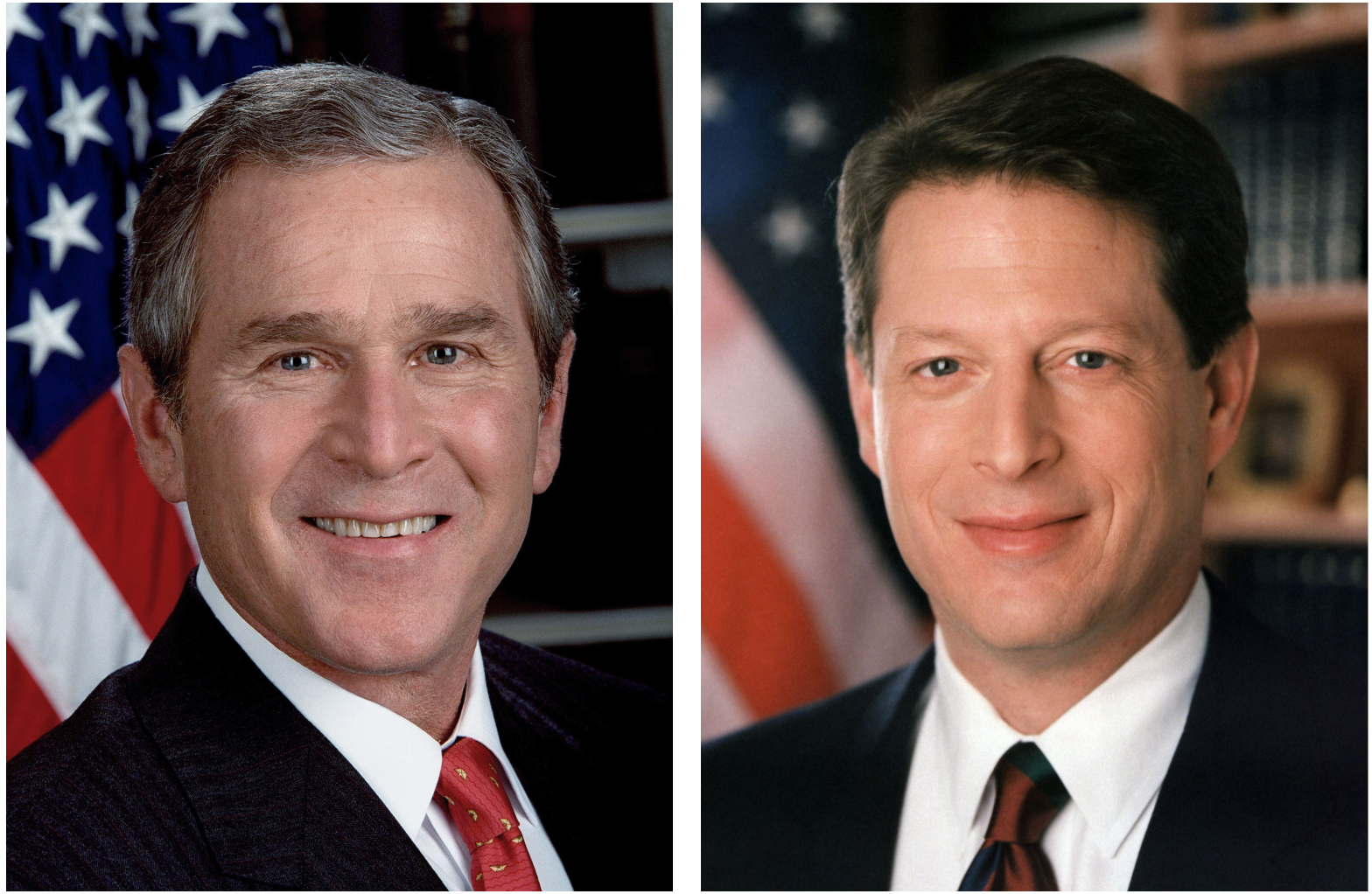

That result was highly controversial because his opponent, Albert Gore, Jr., won the national popular vote by over half a million, which was roughly 0.5% of all votes cast. For the first time in modern U.S. history, the candidate who won the popular vote had been defeated.

In a way, the entire controversy stemmed from what sociologist Robert Merton liked to call “the law of unintended consequences.” That phrase has come to be understood as a warning that intervention in a complex system tends to create unexpected and often undesirable results.

The U.S. Constitution is one such complex system, and making changes to it can sometimes produce those kinds of outcomes. The change at issue here is the little-remembered 20th Amendment, which was adopted in 1933. It shortened the interval between the presidential election and inauguration of the winner from about four and a half months to two and a half months.

Instead of inaugurating the newly elected president on March 4th, as had been the practice earlier, he or she would be sworn in on January 20th. The 20th Amendment also shrank the interval between the election and the swearing in of newly elected members of Congress. Henceforth, their terms would commence on January 3rd.

Those changes were made to prevent a recurrence of the situation that took place in the winter of 1932-33, when the defeated incumbent Herbert Hoover remained in office until March 4, 1933.

The newly elected president, Franklin Roosevelt, was unable to take any steps to combat the Great Depression until then, during a time of real economic emergency, while Hoover remained rigidly resistant to changing the government’s economic policies.

Making the changes contained in the 20th Amendment substantially reduced the likelihood of a similar period of governmental paralysis during a crisis, but unintentionally created a different kind of problem.

One of the virtues of the old, longer interval between Election Day and Inauguration Day was much more time to resolve a disputed presidential election.

One can argue that with the adoption of the 20th Amendment, the old way (provided in the Constitution) of letting the newly elected Congress resolve such disputes became unworkable. Even if the new Congress managed to resolve the dispute on the first day of its existence (January 3rd), that would leave only two and a half weeks for the incoming presidential administration to get ready.

Making that challenge even greater was the huge expansion of presidential power that took place during the twelve years of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency as a result of the need to deal with the Depression and then wage World War II. Those twin crises helped create the modern presidency, which was vastly bigger than it had been when the 20th Amendment was adopted.

Also changed, in a truly permanent way, by World War II was the U.S. government’s role in world affairs. Now greatly enlarged, it required an administration’s senior posts be filled by the first day of its existence, lest the country’s national security be endangered.

That problem remained only a potential one until the disputed election of 2000. It created the possibility that no one would know for sure which candidate had won until January 3, 2001, at the earliest.

Into that perilous situation stepped the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in its decision in Bush v. Gore, reinterpreted the relevant federal statute governing the states’ reporting of their presidential election returns.

The wording of the law on its face seemed to say that if a state wanted to be sure that its returns would be counted, it needed to report them by December 12th. The implication was that if they came in after that, Congress would decide whether to accept them.

That understanding of the law was consistent with what had happened after the 1960 presidential election, when the new state of Hawaii, where the vote had been very close, submitted its final corrected returns after December 12th and the new Congress that convened in January 1961 had accepted them.

The crucial difference between that situation and the one in 2000 was that Hawaii’s 3 electoral votes were not decisive in determining the outcome of the 1960 election, but Florida’s 25 were pivotal to the 2000 one.

Thus, what the majority of the Supreme Court appeared to say in Bush v. Gore was that a state could turn in its election results after December 12th, but only if they were not needed to figure out who had won the Electoral College tally (and thus the election).

If those election results were decisive, however, a state must report them by December 12th. (As George W. Bush was still narrowly ahead in the Florida recount as of December 12th, he won that state and thus the election.)

That piece of creative statutory interpretation solved the problem that the 20th Amendment had created, but not in a way everyone found satisfactory.

The four dissenters (Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, David Souter, and John Paul Stevens) seemingly disagreed with the unstated premise that allowing the Florida recount to go on past December 12th would undermine the effort to form a new administration in a timely manner and thereby endanger national security.

What made matters worse was the rather opaque nature of the opinion for the Court, which was issued for the Court (i.e., “per curiam”) rather than under the name of any justice in the five-person majority (composed of Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, William Rehnquist, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas).

Instead of admitting openly that the Court had decided the case primarily on policy grounds, the majority chose to present its interpretation of the relevant federal law as simply the result of reading the existing statute and applying its provisions to the legal dispute at hand.

The reluctance to be clearer about what the majority was doing reflected, one suspects, a longstanding belief that the public doesn’t entirely approve of the Supreme Court functioning as a partly political body rather than a purely legal one. The famed political scientist Robert Dahl once expressed that thought as follows:

“To consider the Supreme Court of the United States strictly as a legal institution is to underestimate its significance in the American political system. For it is also a political institution, an institution, that is to say, for arriving at decisions on controversial questions of national policy.”

Thus, Bush v. Gore remains historically significant not just for determining the outcome of the 2000 presidential election, but also as a reminder of just how contested the Court’s role remains in the American governmental system.

![]()

Read More:

Stuart Banner, The Most Powerful Court in the World: A History of the Supreme Court of the United States (2024)

Jill Lepore, We the People: A History of the U.S. Constitution (2025)

James Patterson, Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore (2005)

Jeffrey Toobin, Too Close to Call: The Thirty-Six Day Battle to Decide the 2000 Election (2002)

Charles Zelden, Bush v. Gore: Exposing the Hidden Crisis in American Democracy (2010)