“If we had known then what we know now of these swells, and the tides they create, we would have known earlier the terrors of the storm which these swells...told us in unerring language was coming.” —Dr. Isaac Cline

Today, the National Weather Service (NWS) is trusted to provide timely warnings for hurricanes to the residents of the United States. But that was not the case in 1900 for its predecessor, the U.S. Weather Bureau, which began trying to predict hurricane tracks two years earlier. The result was a tragedy that reshaped the Gulf Coast and led one man to devote himself to the study of hurricanes.

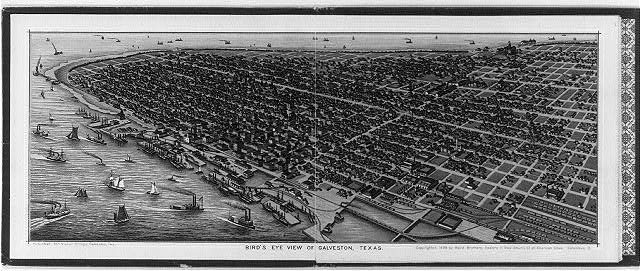

In the summer of 1900, Galveston was the pride of Texas and the richest city on the Gulf Coast. A popular vacation destination, many wealthy Americans had homes in Galveston, particularly along Broadway, and consequently it was the first city in Texas with modern utilities such as electricity, gas, and telephones.

The thriving island city of almost 38,000 had just that year had surpassed New Orleans to become the leading cotton port in the U.S. Travelers could get direct steamships to Europe, Cuba, and Mexico, and connections to Japan and East Asia, while railroads brought the Texas cotton crop and summer visitors alike.

But the city was built on a barrier island formed by deposits of sand and silt, 27 miles long and no more than three miles wide at any point. In 1900, Broadway, the highest point in the city, was only 8.7 feet above sea level, while the average elevation was barely more than four feet.

The dangers of storm surge, a column of churning water beneath the storm’s eye that can be drawn up to surge over the land at a height of fifteen feet or more, were not yet recognized.

In fact, many Galvestonians in 1900 believed that the island was immune to hurricanes, generally called tropical cyclones or simply “floods.” Dr. Isaac Cline, the local forecast official and section director for the U.S. Weather Bureau (1889-1901), had in fact told them so.

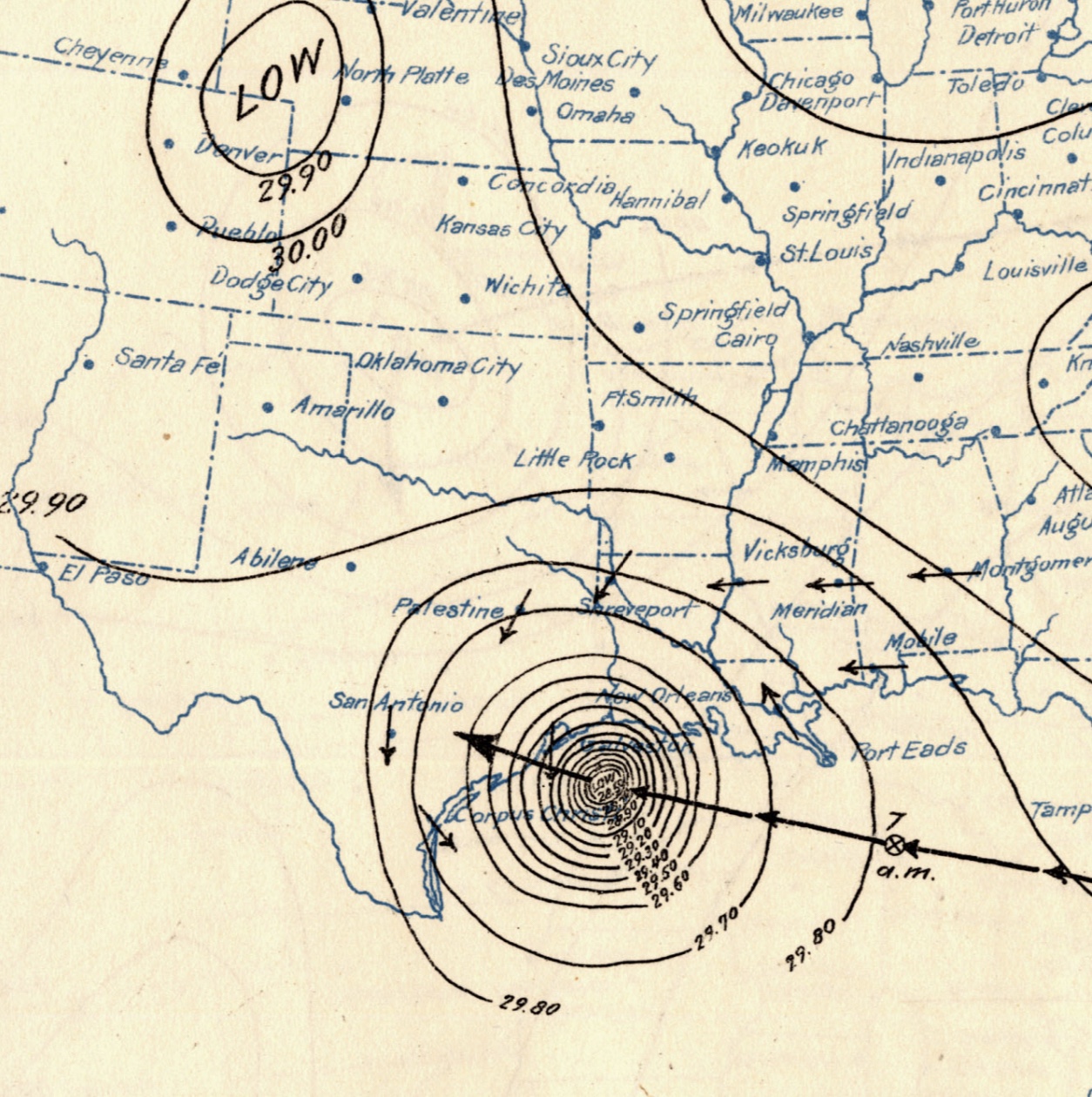

The U.S. Weather Service itself had relatively little data on tropical storms but ignored and even blocked tropical storm warnings from the experienced hurricane researchers at Belen Observatory, Cuba, who recognized that the September 1900 storm was moving into the Gulf.

The U.S. Weather Service forecast the storm to move up the Atlantic Coast instead. Since the first ship-to-shore telegraphy did not become available until 1905, ships in the Gulf caught by the storm could not transmit warnings that would have allowed the storm to be tracked accurately.

On Friday, September 7, Cline went to the beach and timed the waves, finding that the intervals between swells was as much as five minutes, which made him uneasy, as did the rising tides. But Bureau officials in Washington did not change their forecast, despite the warnings from Belen Observatory, until midday Friday.

Even then, the warning was only for a moderate storm, not a hurricane. But the unusual swells recorded by Cline were an indicator of a high storm surge to come, a connection that forecasters did not yet recognize.

On Saturday morning, September 8, Cline informed a skeptical ship’s captain that the storm was not expected to be severe. It was not until mid-afternoon that Cline recognized, based on storm tides and a drop in barometric pressure, that there was a potentially catastrophic hurricane. The storm had cut off telegraph lines and railroad connections to the mainland shortly after noon, however.

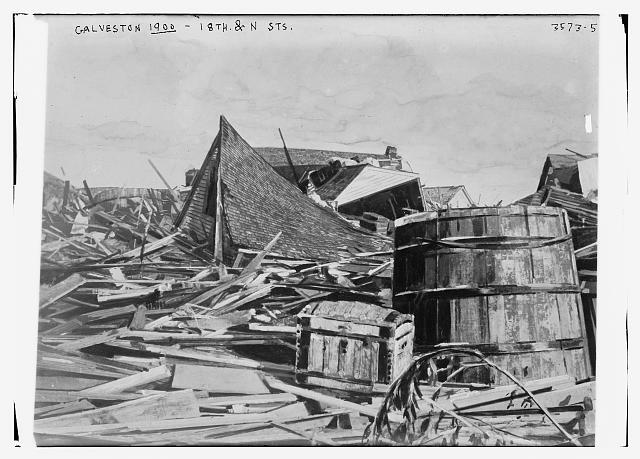

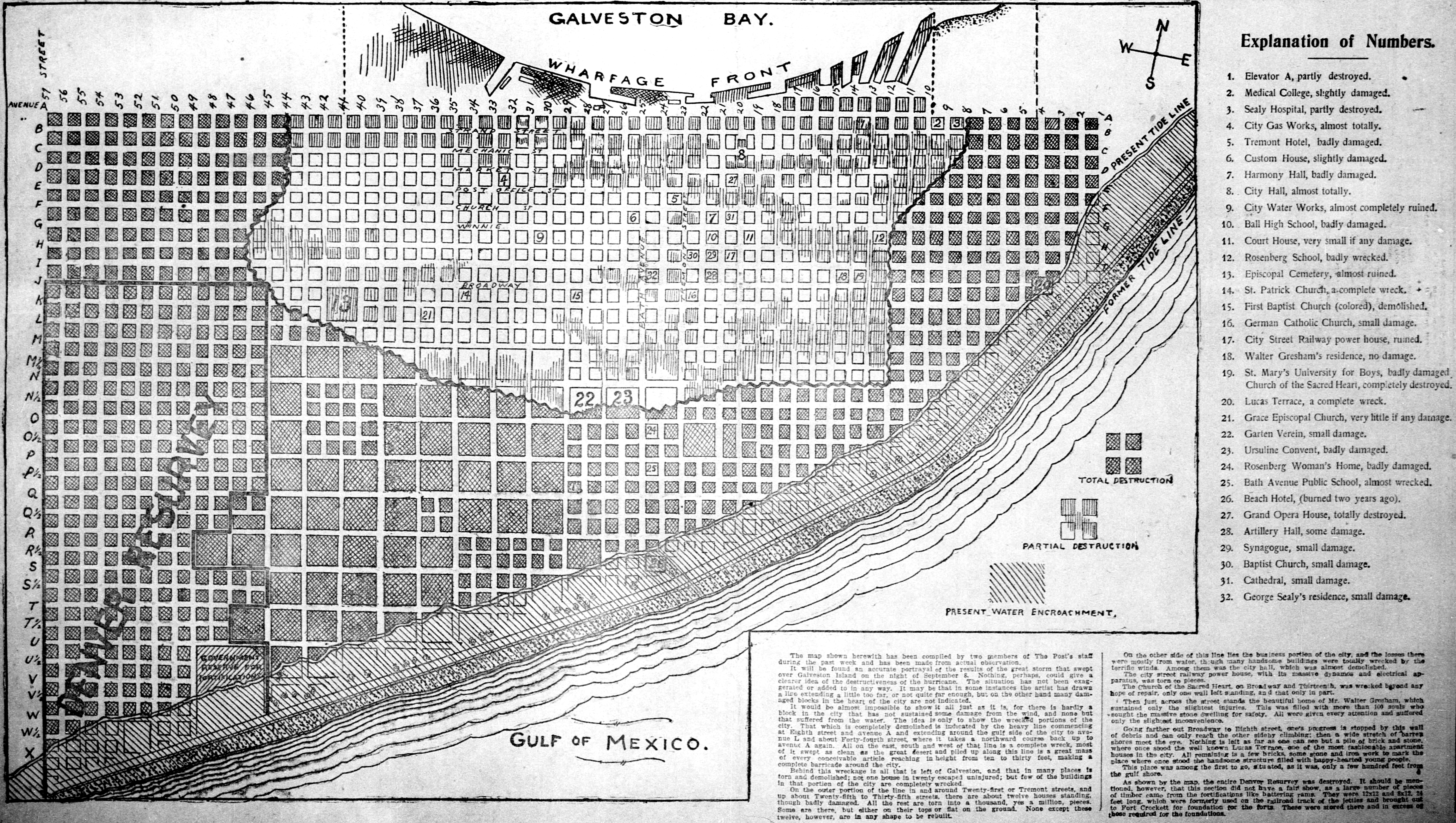

By early evening, the hurricane reached the island, and the devastating storm surge quickly began to take its toll. Indicators of storm intensity under the Saffir-Simpson scale, first introduced in the early 1970s, include the height of the storm surge and barometric pressure. With a storm surge of around fifteen feet, possibly more, and an estimated low barometric pressure of 27.49, the 1900 storm is generally accepted to have been a Category 4 storm.

While most people near the beach evacuated, Cline’s own family, including his brother Joseph, took in about fifty other people on the assumption that his house, several blocks from the beach, would survive any storm. It did not. It collapsed, as did a majority of other houses, when struck by tons of debris carried by the storm surge, and thirty-three of those sheltering in the house died.

The best estimates of the death toll are at least 6,000 people in Galveston alone, and about 10,000 total for the storm, though the number may have been even higher. Many families, some of them visitors, completely vanished. At St. Mary’s Orphanage, 90 children and ten nuns died; only three children survived.

Beyond the tragic losses in people and property, the consequences for Galveston were far-reaching. While the city was rebuilt, raising the elevation of the city by several feet and building a seawall for protection, it never entirely recovered. Houston soon replaced it as the premier Texas port.

Cline’s pregnant wife, Cora, was a victim of the hurricane, but he and his brother Joseph saved Isaac’s three children. Inspired by his loss and the catastrophe, he made the study of hurricanes his life’s work, becoming one of the leading hurricane experts for the Bureau. He established, scientifically, that storm surge was the most dangerous aspect of hurricanes, not direct wind damage, and identified the warning signs that allowed more accurate evacuation orders.

While there have been notable hurricane disasters like Katrina in recent decades, the death tolls for these storms were a fraction of the Galveston Hurricane of 1900. The NWS’s National Hurricane Center is now Americans’ primary source of storm warnings, and evacuation orders generally focus on those most at risk from storm surge.

While the Galveston disaster shook faith in the ability to forecast hurricanes at the time, it also drove researchers like Cline to study these storms, enabling tracking and forecasts that would have been unimaginable in 1900.

Learn More:

Larson, Erik. Isaac’s Storm: A Man, A Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History. New York: Vintage Books, 2000.

Bixel, Patricia Bellis, and Elizabeth Hayes Turner. Galveston and the 1900 Storm: Catastrophe and Catalyst. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000.

Cline, Isaac, Storms, Floods, and Sunshine, New Orleans: Pelican, 1945.

Digital collection of the Galveston History Center, Rosenberg Library.