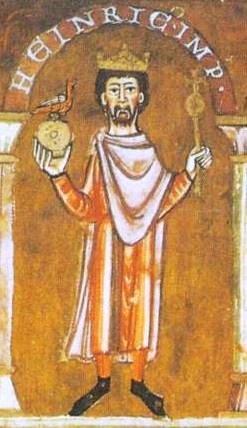

In December 1075, King Henry IV of Germany celebrated the Christmas holidays at Goslar, his favorite castle in Saxony. All seemed to be well: Henry had secured a decisive victory over rebels in the duchy, appointed a new archbishop in Milan, and named two additional bishops in Italy in the last year.

But during the Christmas celebrations, three royal envoys returned from Rome with a letter from Pope Gregory VII, who hadn’t interpreted Henry IV’s actions in Italy in such a favorable light.

Instead, Gregory VII chastised Henry IV’s association with excommunicated advisers and his appointment of three Italian prelates. He demanded obedience to the papacy and threatened excommunication otherwise.

Gregory VII’s admonition ignited, over the course of 1076, an open conflict between the German king and the pope that had been simmering since Gregory VII’s election in 1073.

Henry IV clung to a traditional view of the rights of German kings that gave them certain authority within the religious world. Gregory, in contrast, argued that the papacy, as the representation of God on earth, should have the ultimate authority.

These two viewpoints were inherently at odds, and the break between the papacy and the king in 1076 plunged the German kingdom into civil war.

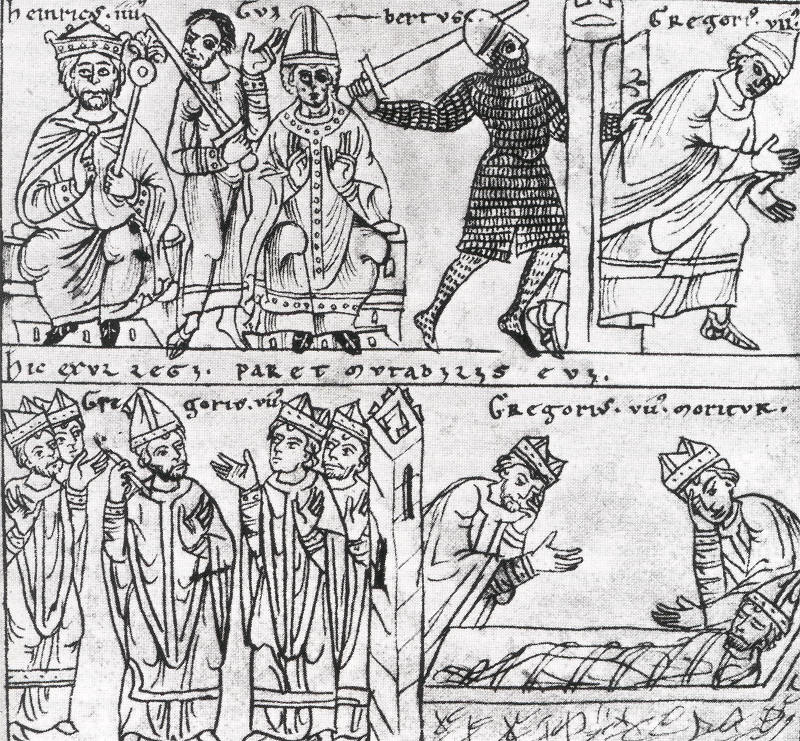

In January 1076, Henry gathered German bishops in the city of Worms and called for Gregory to give up the papacy. The German bishops addressed a letter to the pope that outlined the charges against him: He had stolen the title of pontiff, sowed discord in the Church, and tainted the Church by his close association with Countess Matilda of Tuscany, who independently ruled the march of Tuscany and proved to be Gregory’s most devoted supporter.

These accusations were brought to Gregory in Rome. As a result, Gregory followed through on his warning: Henry IV was excommunicated. Gregory even went a step further, denying Henry his kingship, absolving everyone of their oaths to the king, and forbidding anyone to serve Henry as king.

The ramifications of Gregory’s excommunication of Henry IV were immediate and profound.

The Saxon princes rebelled against Henry again in 1076, and the bishops who had originally denounced Gregory at Worms quickly left the king’s side and tried to reconcile with the papacy.

Henry also faced deposition by the other German princes in October. He was forced to concede to their requests, which included dismissing his excommunicated advisers and promising to reconcile with Gregory. As winter arrived in 1076, Henry IV found himself in a much weaker position than the year before—despite numerous efforts to sway support in his favor.

An opportunity for reconciliation came in early 1077. Gregory was traveling north to meet with the German princes, escorted by Matilda of Tuscany. After crossing the Alps, Henry intercepted the pope at Matilda’s castle at Canossa in one of the most dramatic and memorable scenes of this conflict.

For three days, Henry stood barefoot in the snow outside the walls of Canossa until Gregory agreed to see and reconcile with him—but this was only after Matilda of Tuscany, Countess Adelheid of Turin, and Abbot Hugh of Cluny intervened with the pope on behalf of the king.

Henry gained some immediate benefits from the meeting—namely, Gregory abandoned his plan to intervene in Germany and lifted his excommunication. But Henry’s public penance suggested that he recognized the legitimacy of Gregory’s deposition, which he had rejected only months earlier, and by extension that he acknowledged the pope’s right to intervene in and judge secular affairs.

Further disagreements led to a final breakdown of peace between Henry and Gregory in 1080, and the conflict erupted into war between Henry IV and Matilda of Tuscany, who organized her troops in support of the papacy.

Gregory excommunicated Henry again, and Henry elected his own pope, Wibert of Ravenna (who took the papal name Clement III), after attacking Rome in 1084 and forcing Gregory to flee to nearby Salerno under the protection of the Normans. Neither Henry nor Gregory lived to see the conflict finally resolved in 1122.

While war was an immediate outcome of this disruption of the duality of church and monarchy, the Investiture Controversy, as this conflict is often called, was fought as much with words as with weapons.

Supporters of both the king and the papacy wrote prolifically as they tried to understand, condemn, or justify their own position; those churchmen under the protection of Matilda of Tuscany, in particular, wrote extensively as they tried to defend both the position of the papacy in opposition to Henry IV and Matilda’s role as a woman waging a war on behalf of the papacy.

At the heart of these colorful exchanges—the rhetoric of which wouldn’t be entirely out of place in modern political discourse—was a debate over power and who was able to wield it.

It is for this reason that the Investiture Controversy has endured as a poignant historical mirror for key moments in history, such as Otto von Bismarck’s famous declaration to the Reichstag in 1872 that Germany “will not go to Canossa” as Henry IV did in 1077.

The question of power and authority between the secular and religious at the forefront of debate in the eleventh century has remained perpetually relevant.

![]()

Learn More:

Blumenthal, Uta-Renate. The Investiture Controversy: Church and Monarchy from the Ninth to Twelfth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995.

Cowdrey, H. E. J. Pope Gregory VII, 1073–1085. Oxford, 1998.

Cushing, Kathleen G. Reform and the Papacy in the Eleventh Century. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Hay, David J. The Military Leadership of Matilda of Canossa, 1046–1115. Manchester University Press, 2008.

Imperial Lives and Letters of the Eleventh Century. Translated by Theodor E. Mommsen and Karl F. Morrison. Columbia University Press, 2000.

Miller, Maureen C. Power and the Holy in the Age of the Investiture Contest: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford, 2005.

Robinson, I. S. Henry IV of Germany, 1065–1106. Cambridge University Press, 2000.