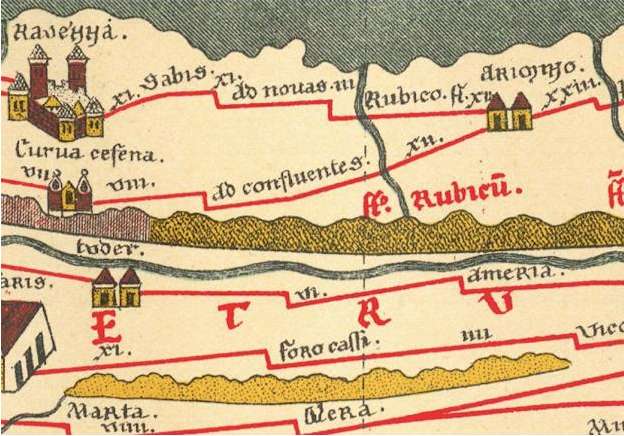

One damp and chilly January night in northern Italy—in what was then Cisalpine Gaul, or today’s Emilia Romagna—the statesman and accomplished general Julius Caesar crossed the little Rubicon River in possession of an army. This event in 49 BCE set off the Roman Civil War, which ended with Caesar’s victory—and enabled Caesar to become, essentially, the sole ruler of the Roman state.

Caesar developed a template for a Roman autocratic rulership that would have appalled his Republican ancestors, but that enabled his adopted son Octavian to become the first emperor of the Roman Empire. Considering what was to come, the crossing of the Rubicon appears as an irreversible step on the way to the Roman Republic’s fall. The Rubicon—a Latin name for an unimportant river—is in fact such a “significant figurative boundary” that it snakes its way through most English dictionaries.

Though the crossing of the river Rubicon marked the beginning of the Roman Civil War, it was just one moment in the conflict between Caesar and fellow Roman statesman and general Pompey (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus) that had been growing for years. The two men were temporary allies, part of the so-called Great Triumvirate. However, when their third ally, Marcus Crassus, died shortly after the death of Julia, Caesar’s daughter and Pompey’s wife, the pact was essentially finished.

By that time (53 BCE) Caesar and Pompey’s divergent contexts put them even more at odds. Caesar was conquering Gaul, gaining prestige and money, and garnering goodwill from the Roman people. Pompey, on the other hand, remained in Rome despite his active command in Spain, and was increasingly aligning with Senate conservatives who opposed Caesar fiercely and at all costs.

Three years later, the situation was growing untenable. Caesar retained his army in Gaul, even though his command there was winding down. His allies in Rome obstructed senatorial attempts to make him give up his army and return as a private citizen.

All Caesar wanted, he claimed, was to run for consul while retaining his military command and to receive a military triumph in Rome to celebrate his conquests. Pompey and much of the Senate, for their part, saw an emerging autocrat making demands and amassing an army that was too loyal for their comfort.

Caesar was to some degree hamstrung, though. He knew the Senate would likely not accept his fair election as consul even if he complied with their demands, and senators opposing him had increasingly disregarded the Republic’s legal processes as the conflict grew.

On January 7, 49 BCE, the Senate issued a decree called the Senatus Consultum Ultimum that effectively made Caesar into an enemy of the state. The tribunes of the plebs loyal to Caesar, who had vetoed so many measures against him, had now fled.

Three days later, Caesar crossed into Italy and seized the city of Arminium (modern Rimini) with a small but significant army, taking advantage of Pompey’s unpreparedness. As Caesar and his forces moved south, Pompey and much of the Senate fled Rome completely. The Roman Civil War had now begun in earnest, though peace negotiations would continue.

Caesar was left to enter Rome, reinstate the tribunes of the plebs, and fashion himself a benevolent restorer of the rule of law.

The crossing of the Rubicon is one of, if not the, most famous historical turning points. These turning points force us to confront our assumptions about how historical change happens. What changes are inevitable? What historical moments are more contingent, a confluence of countless random variables?

Historians examine the evidence and create context for these great moments in history, but untangling these questions is not just the work of academics: we all find these questions to be as compelling as they are (ultimately) intractable.

These questions interested Roman observers, too. Historians of the period and biographers of Julius Caesar imbued the crossing of the Rubicon with heavy significance. The poet Lucan describes Caesar arriving at the Rubicon and encountering there a vision of Rome personified. The distressed Rome entreats the army to stop, but Caesar, recovering from his fear, asks her and other gods to favor his undertaking, and to blame the one “who made me your enemy” (Lucan, Pharsalia 1.203).

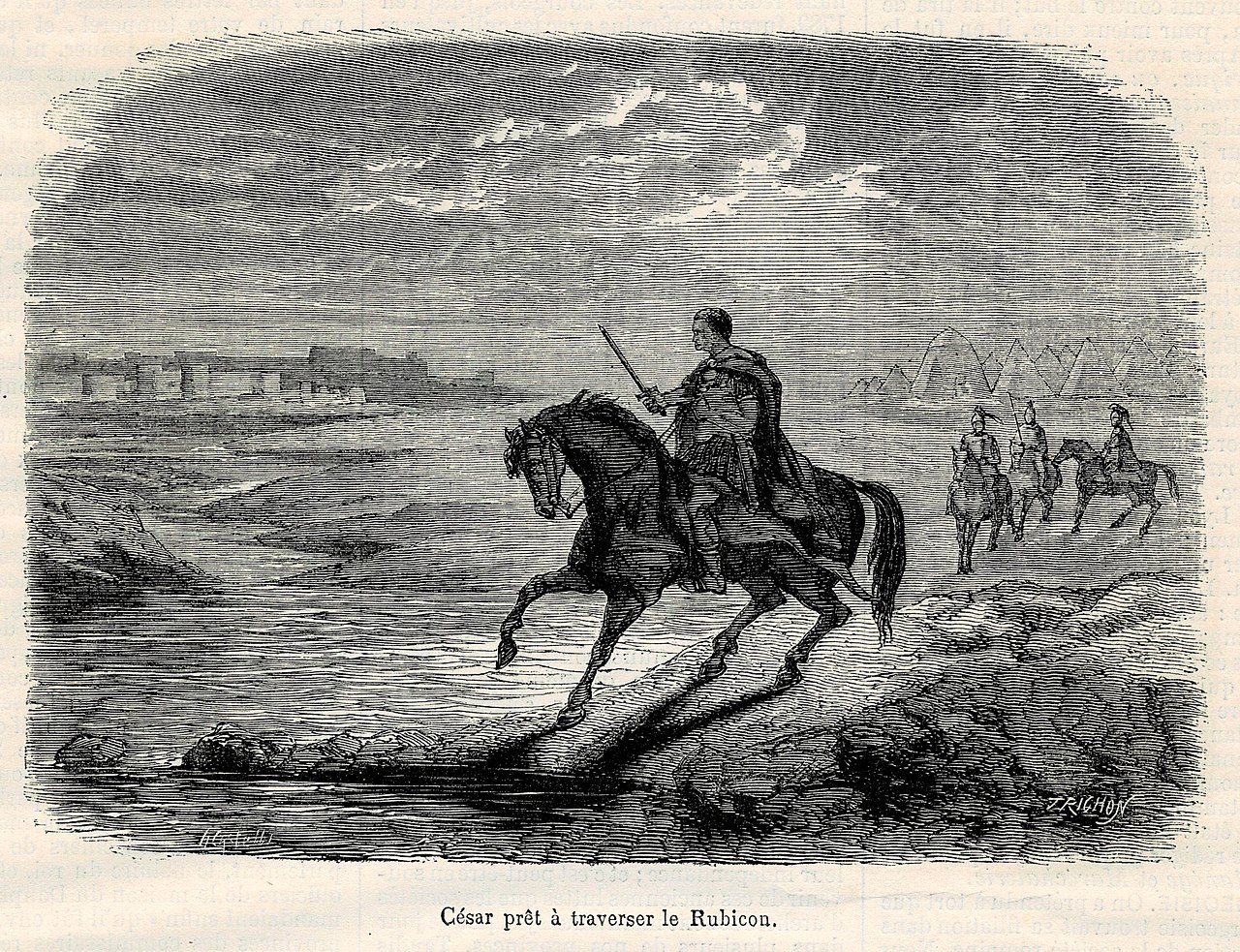

These writers imagine Caesar moving quicky from Ravenna to the Rubicon, but once there he stopped to consider “the enormity of what he was about to set in motion” (Suetonius, Lives 1.31.2). His contemplation, for Suetonius, was interrupted by an apparition that charged across the river sounding a battle-trumpet.

Caesar crossed the river, uttering his famous phrase, “the die is cast,” which Appian wrote that he spoke “like a man possessed” (Appian, Civil Wars 2.35). Plutarch, too, depicts an uncertain and even anguished Caesar who only made up his mind in this moment.

Caesar’s crossing was marked for these authors by supernatural interventions and portents, by his speed but deep concern and contemplation of the impact of his choice, and by his ultimate gambler’s mentality. All these descriptions were written well after the events in question, using perhaps just one relative eye-witness source named Asinius Pollio. They are looking back at a momentous shift in history and seeking to understand it.

Their Caesars contemplate and consider before crossing the Rubicon because they want him to—not just for the sake of Rome, but for dramatic effect. Caesar had, in fact, already decided. His forces had been sent ahead to take control of Arminium. Even more, both Caesar and the Senate had been preparing for the conflict for months, and the Senate’s decree a few days earlier had implicitly declared war.

The fact that rivers were important boundaries, and even divine entities in the ancient world, made the moment at the Rubicon an even more attractive episode. Embellishing the Rubicon moment gave Roman writers a chance to make Caesar confront the gods, himself, and his soldiers, even if his decision was ultimately a gamble.

Cumulatively, these Roman depictions of Caesar’s choice to cross the Rubicon have made a historical mark of their own. Their interpretation stuck: of a solitary man on the precipice of history, as the nineteenth-century French above and below illustrations show.

The civil war that followed the Rubicon was not one man’s choice (or fault); it had been likely for months, if not decades. It was nonetheless a critical juncture. Journalists even today refer to steps forward in conflict as crossings of the Rubicon.

Though the drama and significance of Caesar’s Rubicon was elevated by Roman writers, and its military significance should be contextualized, it helps us think about wars, their causes, and the stories we tell about them.

![]()

Further Reading:

Edward J. Watts, Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny (New York: Basic Books, 2018).

Anke Rondholz, “Crossing the Rubicon: A Historiographical Study,” Mnemosyne 62.3 (2009): 432-450

Robert Morstein-Marx, Julius Caesar and the Roman People (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).