Until recently, historians viewed King Stephen of England (1135-1154) as a failure, sandwiched between two quite successful kings, Henry I (1101-1135) and Henry II (1154-1189). His reign was dominated by The Anarchy (1138-1153), a civil war over royal succession and a period of lawlessness.

In the past decade, however, historians have reassessed Stephen’s reign. While Stephen’s rule was marred by civil war and political setbacks, recent reassessments have highlighted his resilience, military skill, and the continuity of Henry I’s effective administrative system in the regions Stephen controlled.

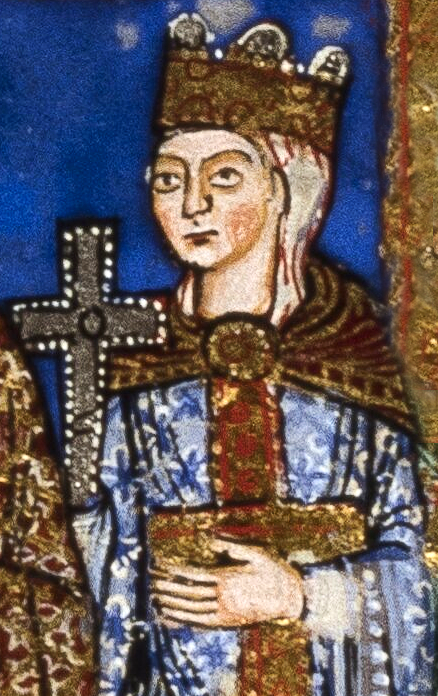

They have also highlighted the influential role of his queen, Matilda. Queen Matilda was Stephen’s indispensable partner, participating in military, diplomatic, and political efforts and governing the realm while Stephen campaigned.

At the same time, scholars have revised their view of a different Matilda, Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I, who fought Stephen for the throne. They now portray her as a skilled political strategist who, despite failing to secure the crown for herself in her struggles with Stephen, successfully ensured her son’s succession.

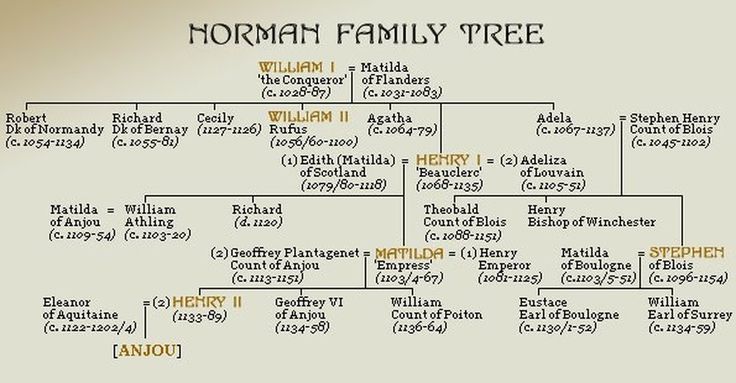

Stephen (1092–25 October 1154) was the fourth son of Stephen-Henry, Count of Blois, and Adela, daughter of William the Conqueror. Raised by his mother after his father’s death on crusade, Stephen entered the court of his uncle, King Henry I of England, where he gained favor and lands.

The death of Henry I’s only legitimate son, William, in 1120, left the succession uncertain.

Henry remarried, hoping for a male heir, but also arranged Stephen’s marriage in 1125 to Matilda, heiress to the Honour of Boulogne in England and Boulogne in northern France.

In 1126, Henry also brought his widowed daughter, Empress Matilda, back to England as his heir.

At the court in London in January 1127, nobles—including Stephen—swore to uphold her claim. Her marriage to Geoffrey of Anjou in 1128 created tensions, tying her to southern Norman and Angevin alliances and alienating many Anglo-Norman nobles. While she built strong ties with Robert of Gloucester and his circle, she had few allies in England.

At Henry I’s death in December 1135, Stephen was a central figure in Anglo-Norman society, admired by both nobles and commoners for his wealth, charm, and decisiveness.

Stephen swiftly crossed the Channel to claim the kingdom, capitalizing on Empress Matilda’s absence in Normandy when Henry I died. With support from Londoners and the Church—secured through his brother Henry bishop of Winchester—Stephen was crowned king.

His early reign was marked by diplomatic success, including peace with Scotland and France, and stability in Normandy, bolstered by northern French allies. However, deeper issues emerged: Scotland retained northern territories, Wales was neglected, and some barons felt unrewarded.

One of these was Robert of Gloucester, who in 1138 rebelled against Stephen in support of Empress Matilda. He was joined by nobles in his circle and King David of Scotland.

Stephen successfully moved against Gloucestershire and his army defeated Scottish forces at the Battle of the Standard. Queen Matilda played a key role in retaking Dover and negotiating peace with Scotland through the Treaty of Durham.

Next, Stephen expanded the number of earldoms, rewarding loyal military leaders and fortifying vulnerable regions, increasing the nobles’ autonomy.

He also moved against three powerful royal administrators, who were also bishops, suspecting them of disloyalty. Their arrest strained relations with the Church. His brother Henry viewed the crackdown as a breach of ecclesiastical liberty.

The civil war escalated in 1139 when Empress Matilda landed in England. Stephen besieged her at Arundel Castle but released her, either out of chivalry or strategic calculation. Matilda joined her allies in the southwest.

The period known as “The Anarchy” had now begun.

The conflict peaked in 1141 when Stephen confronted Robert of Gloucester and Ranulf of Chester at Lincoln. Despite his bravery, Stephen was defeated and captured, allowing Empress Matilda to pursue the throne. Though she gained recognition from the English Church and control of London, she quickly lost momentum.

Empress Matilda refused to heed counsel and dismissed appeals for mercy, thereby violating norms of political friendship, good lordship, and womanly behavior. Her imperiousness undermined her legitimacy.

In contrast, Queen Matilda embraced feminine norms to rally Stephen’s supporters, retake London, and regain church and noble allegiance. Her commander turned the tide at the Rout of Winchester, capturing Robert of Gloucester. A prisoner exchange restored Stephen, and he and Queen Matilda were re-crowned at Christmas 1141.

From 1142 to 1150, neither side gained a decisive advantage. The civil war dragged on, plunging England into lawlessness. Unauthorized castles proliferated, and royal authority failed in conflict zones. After Robert of Gloucester’s death and Empress Matilda’s return to Normandy in 1147, warfare waned. Her son Henry made two failed invasions in 1147 and 1149.

Stephen sought to secure his son Eustace’s succession, but the Church refused to anoint him. He suffered another setback with Queen Matilda’s death in May 1152.

Though Henry failed militarily, he forged alliances, and his 1152 marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine greatly increased his power.

In 1153, Henry launched another campaign; Eustace’s sudden death and a standoff at Wallingford led to a truce and peace agreement ratified at Winchester. Stephen would rule until death; his son William inherited family lands, and Henry would succeed to the throne.

Stephen died in October 1154, buried next to Queen Matilda at Faversham Abbey. Henry II was crowned in December 1154.

Empress Matilda herself never ruled as queen, but as Lady of the English, she governed southwest England. Her persistence and political maneuvering ensured the continuation of her lineage on the English throne. Henry II relied upon her expertise to govern in his absence in Normandy during the first years of his reign.

By the end of his reign, Stephen had laid the groundwork for a peaceful transition to Henry II, whose rule would extend royal authority through administrative innovations. Stephen’s legacy, once dismissed, now appears as a crucial bridge between the Norman and Plantagenet dynasties.

![]()

Learn More:

Jim Bradbury, Stephen and Matilda: the Civil War of 1139–53 (History Press, 2000).

David Crouch, The Reign of King Stephen, 1135–1154 (Longman, 2000).

Edmund King, "The Anarchy of King Stephen's Reign," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 5th series 34 (1984): 133–153.

Heather J. Tanner, “Matilda of Boulogne: The Indispensable Partner,” in Norman to Early Plantagenet Consorts, edited by Aidan Norrie, Carolyn Harris, J. L. Laynesmith, Danna R. Messer, and Elena Woodacre, 99–118. New York: Palgrave, 2023.

Elisabeth van Houts, Empress Matilda. Queen of the Romans, Ruler of the English (Yale University Press, 2026).

Graeme White, “Continuity in Government,” in The Anarchy of King Stephen's Reign, ed. by Edmund King, 117-144. Clarendon Press, 1994.