On July 25, 1966, the great Ted Williams used his Hall of Fame induction speech to challenge Major League Baseball (MLB). The Red Sox superstar started with the usual. He thanked his coaches, he talked about hard work, and he praised baseball.

Then, he went where no white Hall of Famer had gone before. He pleaded, “I hope that someday, the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here only because they were not given a chance.”

The omission was especially glaring, because many people considered Paige the best pitcher who ever played. Throughout most of his career, he and his colleagues too frequently heard, “if only you were white,” as a compliment to their skills, but also as a reality check that the big leagues did not want them.

To those who cared that day, Williams’s words struck a chord. As one sportswriter put it, Williams “put his finger on the real weakness of the Hall of Fame.” In the middle of the Civil Rights Movement, barring Paige from the Hall also meant keeping Black history out. In short, the slight told America that Black institutions did not matter.

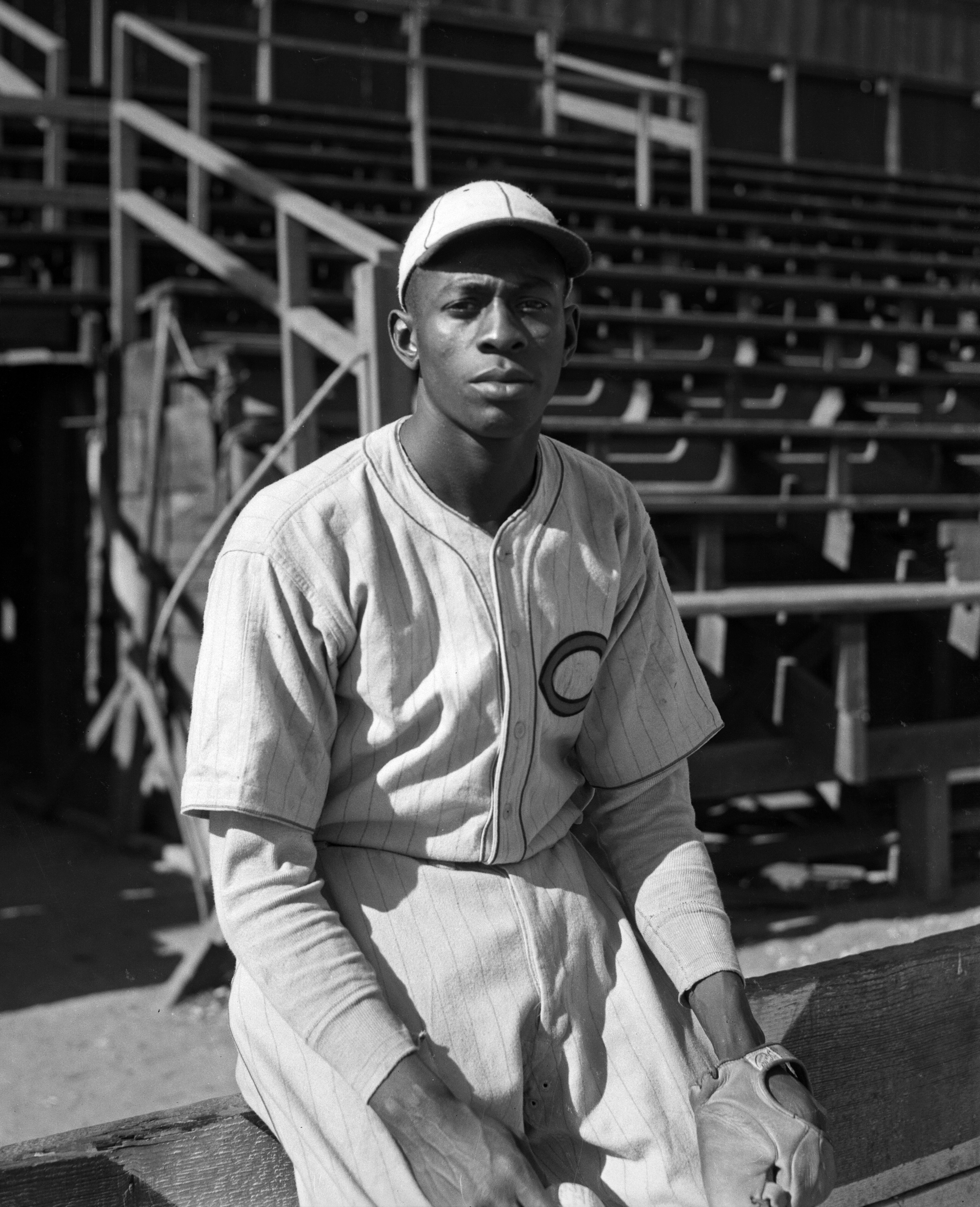

Leroy “Satchel” Paige was born poor in 1906 in Mobile, Alabama. At a young age, to make money for his family, Paige carried visitors’ bags at the train station. As the story goes, he rigged up a pole that allowed him to carry multiple pieces of luggage. His peers joked that he looked like a walking satchel. The name stuck.

Paige was a maestro on the mound. In his youth, he honed his pitching skills killing squirrels with rocks and knocking down butterflies with clam shells. As a professional, he changed his targets from animals and insects to soda bottles, holes in fences, and gum wrappers he placed over home plate to warm up before games.

Ever the showman, he named his pitches. He called his legendary fastball, “long Tom,” and he had a pitch he touted as the “trouble ball.” MLB banned his famed “hesitation pitch,” in which he deliberately slowed down his delivery to get the batter off balance. Then there was the “be-ball,” which he named because, as he said, “it be where I want it to be.”

He was so confident in his abilities that at times he would ask his teammates to sit down while he faced batters. Sometimes, he would intentionally walk the bases full, with no outs, and then proceed to strikeout the next three batters.

For nearly forty years, from 1924 to 1965, his talents attracted teams from all over the western hemisphere trying to get a piece of the show. Everywhere he went, Satchel Paige was the main attraction. And he knew it too. He had no problems jumping his contract to twirl for the highest bidder or jetting to a small town to get the cut of a gate.

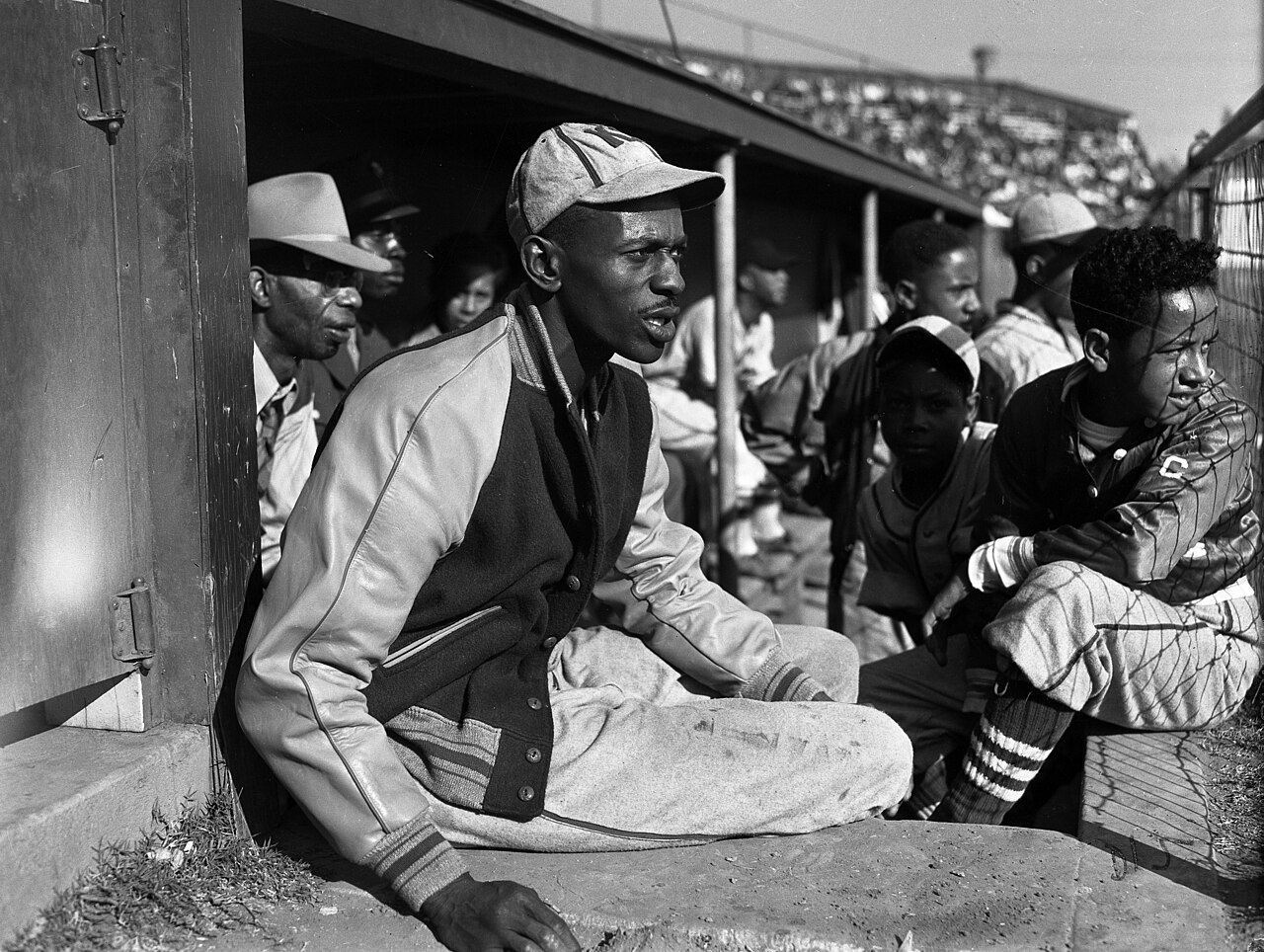

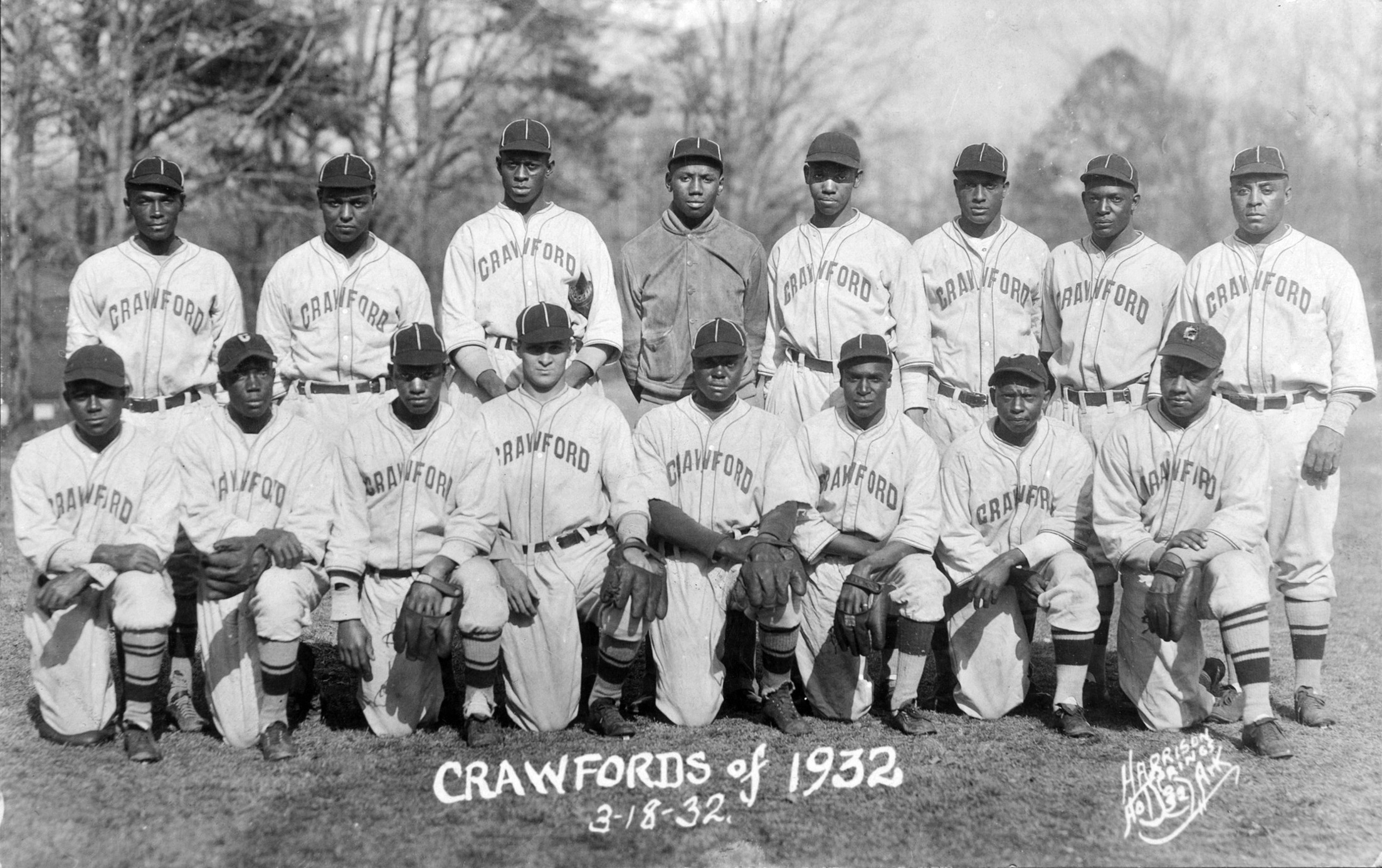

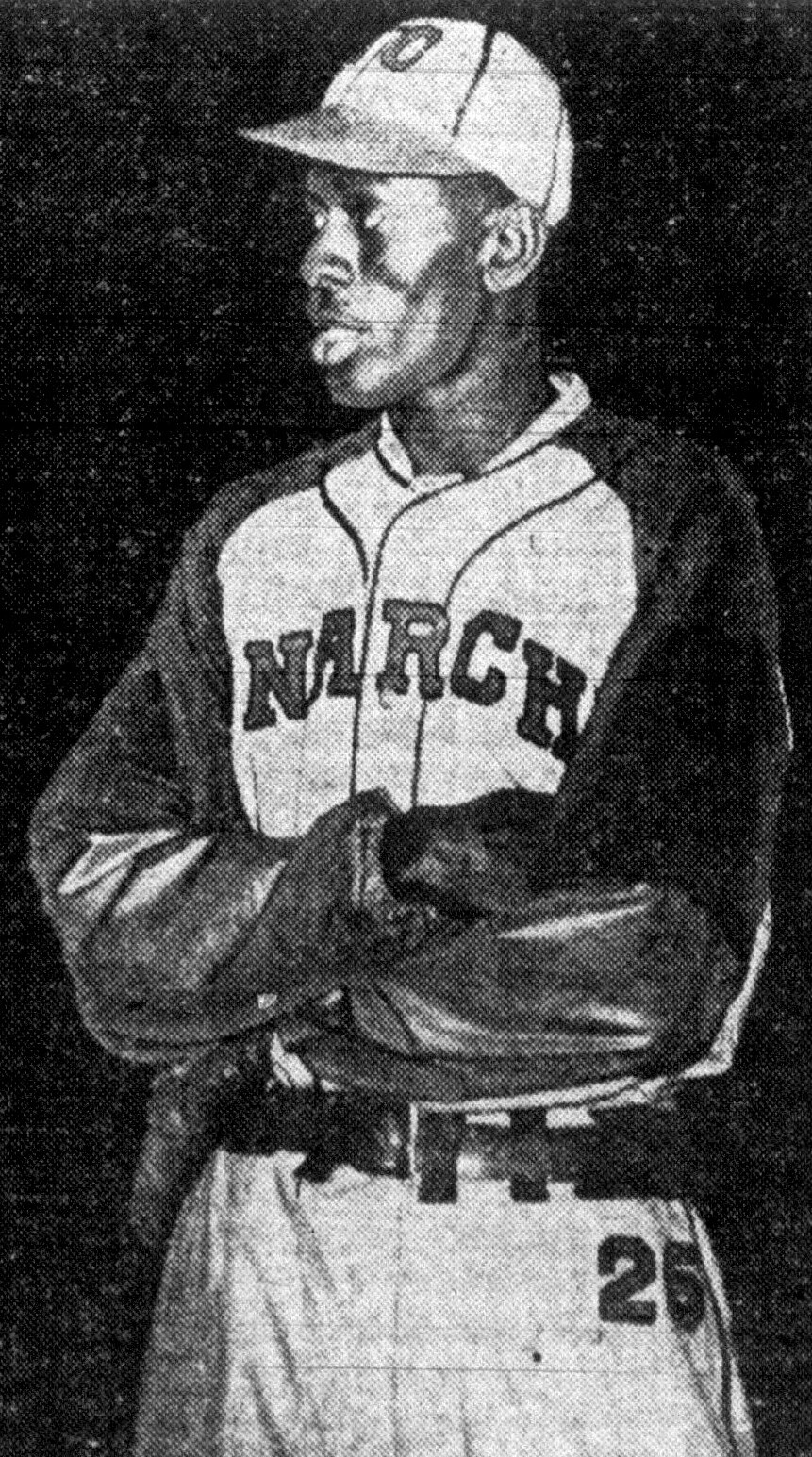

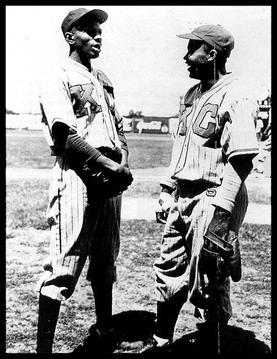

During his career, he pitched for legendary Black teams including the Birmingham Black Barons, the Kansas City Monarchs, and the Pittsburgh Crawfords.

Before MLB integrated, he starred for integrated squads in Bismarck, North Dakota, and traveled to Denver to join the formidable House of David team to win a prestigious baseball tournament. He played in an integrated winter league in Los Angeles, where he dominated Major Leaguers. He also played seasons in the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Puerto Rico.

At his peak, white pundits and players recognized Paige as the best player.

The Cardinals’ Dizzy Dean said if he and Paige pitched together, the Cardinals would win the pennant by the Fourth of July. The Yankee great, Joe DiMaggio, called him the best pitcher he ever faced. In 1940, The Saturday Evening Post labeled him “one of the greatest pitchers of all time.”

The compliments were great, but they might as well have said, “if only you were white.” White owners hid behind a “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” or an understanding between players and owners that pro teams would not sign Black players.

This racist policy lasted from 1887 to 1945, when the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson.

In 1947, when Robinson made his MLB debut, he opened the door for other Negro Leaguers. That season, four Black men made their way to the pros, including future Hall of Famer Larry Doby, who integrated the American League when he signed with the Cleveland Indians.

And then, the next year, in 1948, Cleveland’s maverick owner, Bill Veeck, did the unthinkable. He signed Satchel Paige as a forty-one-year-old rookie. Paige was past his prime, but to the Black community, that did not matter. He was their hero, a flame-throwing representation of Black excellence.

When Paige started his first game, Cleveland broke their attendance record. That season, Paige and Doby also helped Cleveland win the World Series.

Although the team released Paige the following season, Paige resurfaced in 1951 with the Veeck-owned St. Louis Browns. Veeck needed Paige to fill the stadium. The following year, at the age of forty-six, Satchel became the oldest player to pitch a shutout game. He also played in the All-Star Game.

The ageless wonder had to wait thirteen years before he got another chance in the Majors. In 1965, at the age of 59, he pitched three shutout innings for the Kansas City Athletics.

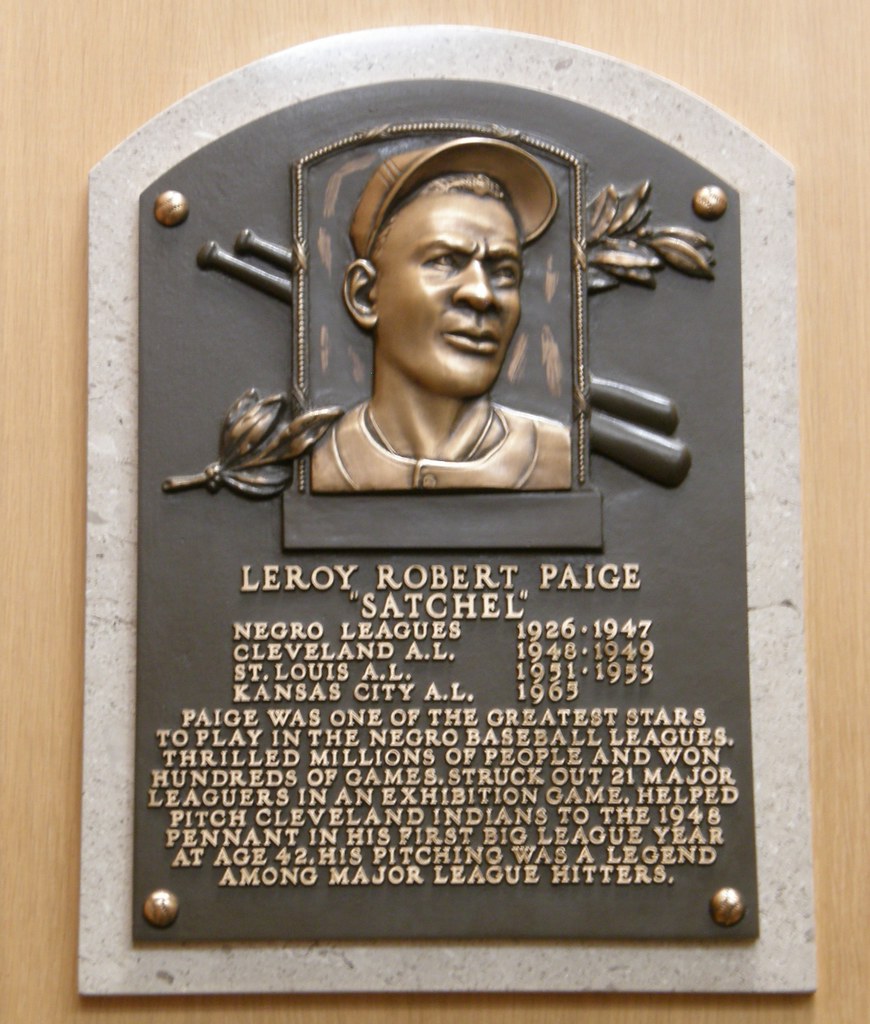

In 1971, Cooperstown finally relented on its discriminatory policy. That year, they created a special committee just for Negro League players, and they inducted Paige as their first member.

Paige only played four of his forty seasons of professional baseball in the Major Leagues. All totaled, it is estimated that he won more than 2,000 games, pitched 300 shutouts, and had at least 55 no-hitters. But one can’t solely measure Paige’s career in stats.

Paige’s induction continues to be significant. Satchel Paige meant something to the Black community. And that matters. Much like his contemporaries, Jesse Owens and Joe Louis, the Black community championed Paige as a symbol of pride. But unlike the other two stars, most of Paige’s production occurred within the structure of a Black institution.

More than just an individual accomplishment, or a sign that baseball had finally righted wrongs, Paige’s induction signaled that Black baseball was also America’s game. The Hall of Fame told Americans something that Black folks already knew: Black institutions and Black history mattered.

![]()

Learn More:

Leslie A. Heaphy, Satchel Paige and Company: Essays on the Kansas City Monarchs, their Greatest Star, and the Negro Leagues. McFarland.

Lawrence D. Hogan and Jules Tygiel, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African American Baseball. National Geographic.

Satchel Paige, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever. Bison Books.

Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues. Kensington Publishing Corp.

Larry Tye, Satchel Paige: The Life and Times of An American Legend. Random House.